AntiD

We will start with the unpacked binary…but fear not, dear reader…it is not left as an exercise to you to figure that out. I have provided the unpacked binary on my github here.

For a walkthrough of how to unpack this binary (and realize it needed unpacking in the first place) see here, here, or here. It would also be worth your while to read Chapter 18 of Practical Malware Analysis if you’re interested in learning more.

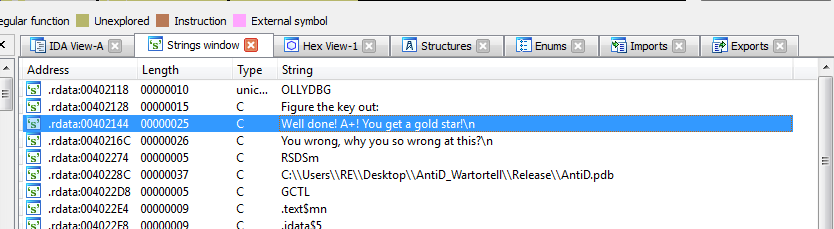

We load the unpacked binary in IDA and take a quick look at the strings (Shift+F12). We see some low-hanging fruit:

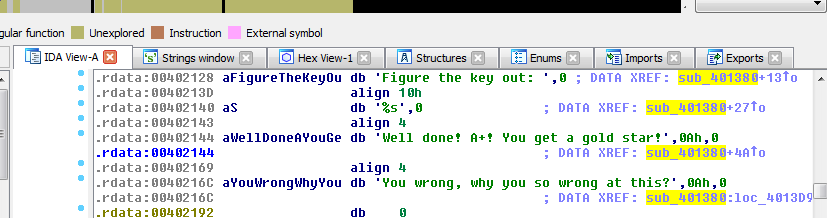

Ok…we double click it to see where it lives.

There is only one cross-reference to this string, and it comes from sub_401380. This sub seems to also make use of other strings that are interesting to us. Double-clicking on this sub takes us to the function of interest.

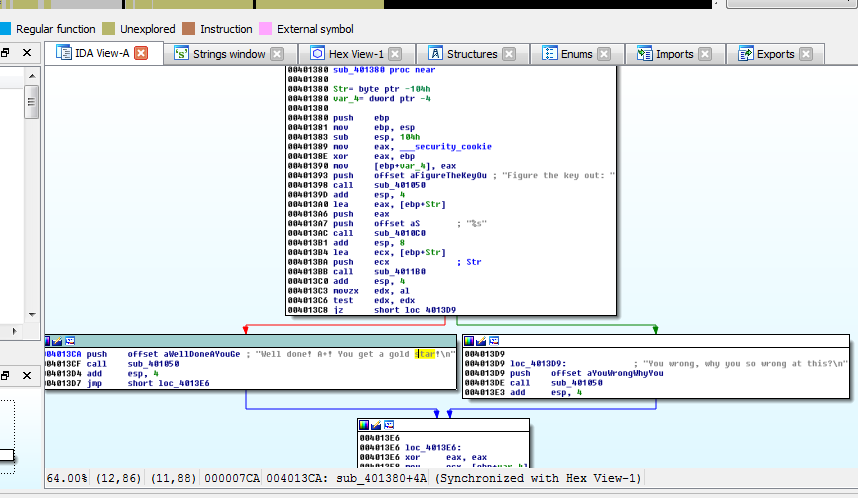

At a quick glance, with IDA’s helpful commenting, we make a reasonably well-founded assumption that

.text:00401393 push offset aFigureTheKeyOu ; "Figure the key out: "

.text:00401398 call sub_401050

is probably a printf for the “Figure” string

.text:0040139D add esp, 4

.text:004013A0 lea eax, [ebp+Str]

.text:004013A6 push eax

.text:004013A7 push offset aS ; "%s"

.text:004013AC call sub_4010C0

seems to be scanf, it takes a pointer to a local var that IDA has labeled Str, and it also takes a possible format string ‘%s’ as another argument.

Next,

.text:004013B1 add esp, 8

.text:004013B4 lea ecx, [ebp+Str]

.text:004013BA push ecx ; Str

.text:004013BB call sub_4011B0

.text:004013C0 add esp, 4

.text:004013C3 movzx edx, al

.text:004013C6 test edx, edx

.text:004013C8 jz short loc_4013

that Str variable, which has now presumably been populated with our input, is used as the argument to sub_4011B0.

When this function returns, whatever was in the al register will be placed into edx with zero extension (fill the rest of the register with 0s). If the test edx, edx (essentially edx & edx) is zero…then we take the true branch of the condition. This leads us to the undesireable message that also calls printf(sub_401050).

Ok, so if we want to win, we know that we must return from sub_4011B0 with something other than 0 in the al register.

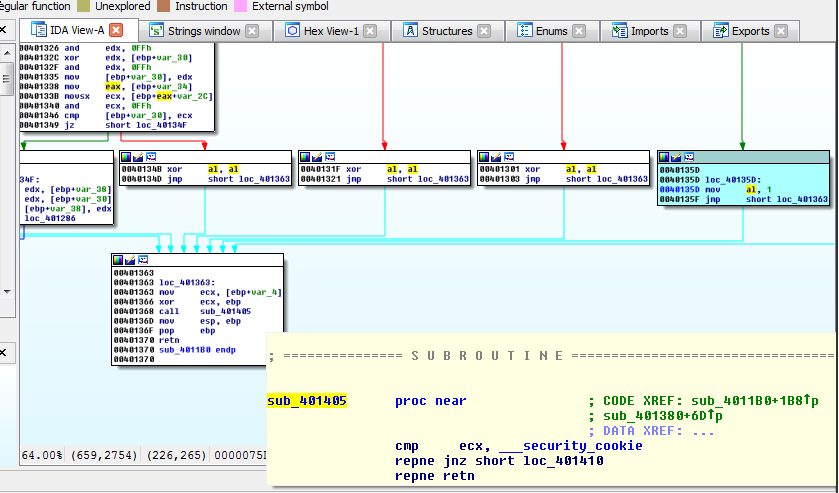

We take a look at what we now believe is the input validator (sub_4011B0), and try to get an idea of how we can achieve our goal.

With the benefit of hindsight, and in the interest of brevity…we examine the possible ways that this function can finish its job and return with our al.

We note that all the edges coming into the basic block which has our retn intstruction, are screwing with our al. There is only one block (highlighted in blue) which will allow us to have something other than 0. We mouse over the sub called just before the return (sub_401405) at 0x401368 just to confirm that it is only a stack cookie check.

Ok, so how do we get to this block?

There seems to be only one edge leading into it, and it seems to be a loop condition:

.text:0040128F loc_40128F:

.text:0040128F cmp [ebp+var_34], 28h

.text:00401293 jge loc_40135D

Pressing x with var_34 highlighted, we can see the places where it’s written and read. Examining these, we can easily confirm the idea that this is our loop counter:

.text:00401286 loc_401286:

.text:00401286 mov ecx, [ebp+var_34]

.text:00401289 add ecx, 1

.text:0040128C mov [ebp+var_34], ecx

It seems likely that our input string is 0x28 characters long.

We are ready to symbolically execute this function using angr

Ok, then let’s start at the top of the flag checking function, and tell angr to explore until it finds a path to the basic block with a 1 in al. We can then examine the memory for strings which have been able to reach the winning basic block.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import angr

# load the binary

b = angr.Project("AntiD_clean.exe", load_options={"auto_load_libs":False})

# create a blank_state (https://github.com/angr/angr-doc/blob/master/docs/toplevel.md#the-factory) at the top of the flag checking function

s = b.factory.blank_state(addr=0x4011B0)

# Since we started inside this function, we have to set up the args that were pushed on to the stack from the previous function

# ...0 sounds like a good place to store memory, why not? So esp+4 (arg0) shall be found at 0

s.mem[s.regs.esp+4:].dword = 0

# let's store a symbolic BitVector (https://github.com/angr/angr-doc/blob/master/docs/claripy.md#claripy-asts) large enough (0x28 * 8 bits) for the proper input (based on the loop exit conditions at 0x40128F

s.memory.store(0, s.se.BVS("ans", 0x28*8))

# instantiate a path_group (https://github.com/angr/angr-doc/blob/master/docs/pathgroups.md)

pg = b.factory.path_group(s)

# ask them to explore until they find the winning basic block

pg.explore(find=0x40135D)

# for those paths which have found a way to the desired address...let's examine their state

for found in pg.found:

# specifically, let's see what string is in memory at 0 for successful paths

print found.state.se.any_str(found.state.memory.load(0, 0x28)).strip('\0')

and then…

# ./antiSolve.py

WARNING | 2017-06-21 22:44:23,145 | cle.pe | The PE module is not well-supported. Good luck!

PAN{C0nf1agul4ti0ns_0n_4_J08_W3LL_D0N3!}

…looks supported enough.

Note that we could have helped angr a lot by adding constraints to our mystery input, and added some avoid addresses for our path_group exploring, and other things like that. It’s not a major concern here because this binary is small and relatively simple, so the script doesn’t take too long.

I hope you enjoyed this post, and maybe learned something.

If you’d like to see more examples of using angr, check out the examples in the angr-doc repo here.

The angr script, the packed, and ‘clean’ binaries are posted on my github.