Level 3: labyrINth

Description:

You walk to the east...

The goblin guarding the door giggles as he describes the next

challenge.

7z Download

7z Password: labyrenth

Hint: You are going to need a virtual machine for this one.

Author(s): @xedi25

http://dl.labyrenth.com/labyrinth/d88b07e6d10481cb716e0c8a78519d2c8bfef2778e0332aef6c4f0699d74be6e.7z

Alternate binary download link

This isn’t going to be a particularly nice write-up, but it is pretty close to how I solved this challenge. This isn’t the in-depth malware analysis edition, we gotta go fast after all. However, you might walk away with a few more IDA, Python, CTF, or debugging tricks. So let’s do it.

Step 0: Hints

With the help of some prior knowledge (Chapter 17 of Practical Malware Analysis), we can see that the hint’s combination of “IN” and virtual machine strongly suggests that we can expect the IN instruction to be an important part of this challenge.

Massaging the google search queries until I find what I know I’m looking for…reveals this helpful article:

Another interesting feature of VMware is seen when executing the IN instruction from user-land of common OSs like Linux, Windows, etc (and more accurately, when executing this instruction in ring3). IN is the “Input from Port” instruction. It copies the value from the I/O port specified with the source operand to the destination operand. The IN instruction is a privileged instruction which cannot be run from ring3 (user-land), therefore when executed, an exception should be thrown. However, when VMware is running, no exception is generated if a special input port is specified. That port is “0×5658,” aka: “VX.” This technique is described in much more detail in the original posting here.

Ok, it is worth going down this rabbit hole, and a google search for “vmware i/o port opcodes” gives us a very useful reference.

Step 1: Initial triage & recon

The usual file + strings combo gives us a starting point:

flag: %s

doesn't look like valid flag to me: %s

VMware version: %u

I don't think you can finish this today.

I don't think you can finish this today. Not with this attitude.

Slow.

Talk to you later.

We do the strings xref thing and find the flag checking function (0x418E10), and main (0x418FC0).

Exploring the area around the “VMware version” string:

PANW:00419026 mov [ebp+var_2A], eax

PANW:00419029 mov [ebp+var_26], ax

PANW:0041902D mov eax, 11h

PANW:00419032 mov [ebp-34h], ax

PANW:00419036 lea ecx, [ebp+var_44+8]

PANW:00419039 call sub_418B00

PANW:0041903E mov esi, dword ptr [ebp+var_44+8]

PANW:00419041 push esi

PANW:00419042 push offset aVmwareVersionU ; "VMware version: %u\n"

PANW:00419047 call sub_407610

PANW:0041904C add esp, 8

PANW:0041904F cmp esi, 4

PANW:00419052 jz short loc_41906F

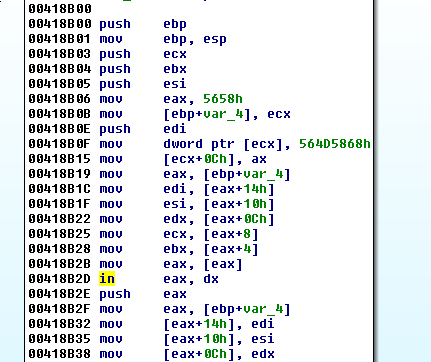

we find the “IN” in 0x418B00

Recognizing that the immediate values here:

PANW:00418B06 mov eax, 5658h

PANW:00418B0B mov [ebp+var_4], ecx

PANW:00418B0E push edi

PANW:00418B0F mov dword ptr [ecx], 564D5868h

have bytes that are all in the printable ascii range [0x20, 0x7E] ($ man ascii), we click on them and press r to see if they spell anything or if it’s just a number:

PANW:00418B06 mov eax, 'VX'

PANW:00418B0B mov [ebp+var_4], ecx

PANW:00418B0E push edi

PANW:00418B0F mov dword ptr [ecx], 'VMXh'

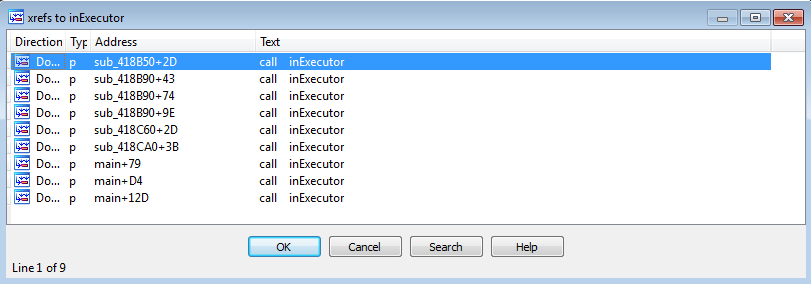

We rename this function inExecutor, and check the xrefs with x.

and it looks like this idea of using the virtual I/O port will be soundly beaten to death by the time we’re done with this challenge. On the bright side, we only have to analyze this function once. We set a breakpoint on the IN instruction, then set a breakpoint on all calls to this function, using IDAPython:

import idc

import idaapi

import idautils

def set_breakpoints_on_calls(ea):

print "Setting breakpoints on ", hex(ea)

for ref in idautils.CodeRefsTo(ea, 0):

print "Adding bpt on ", hex(ref)

idc.AddBpt(ref)

def set_breakpoints_on_screen_ea():

print "Started"

set_breakpoints_on_calls(idc.ScreenEA())

idaapi.add_hotkey("Alt-Z", set_breakpoints_on_screen_ea)

Run this script (Shift+F2 or File -> Script command). Then click on the starting address of this function, 0x418B00. Then press Alt+Z to set a breakpoint on all locations that call this function.

Taking a look at these locations, we see a common pattern of some code calling inExecutor, then branching after a cmp that is presumably using the values returned from inExecutor (either directly or after some calculation). So this may be relatively straight forward:

- Determine which opcode/call is being made through IN

- Read the opcode documentation to see what values are returned where

- See what the code is doing with these values when it returns from inExecutor

- Determine which branch of the conditional jump (based on the return values) is the desireable branch

- Work backwards from the cmp to calculate the value that IN would have returned for a successful cmp.

Step 2: Dynamic Analysis

With these breakpoints set, and a crude understanding…we start the debug/guess-and-check game.

We run the binary and hit the first call to inExecutor. It looks like 0x11 might be our opcode, ecx our buffer that holds a return value…or values? The return value of interest should be 4 in order to jump to the next basic block on the good path.

Looking 0x11 up in the I/O commands reference:

11h - Get virtual hardware version

AVAILABILITY

WS5.x

CALL

EAX = 564D5868h - magic number

EBX = don't care

ECX(HI) = don't care

ECX(LO) = 0011h - command number

EDX(HI) = don't care

EDX(LO) = 5658h - port number

RETURN

EAX = virtual hardware version

EBX = unchanged

ECX = unchanged

EDX = unchanged

DESCRIPTION

This command returns the virtual hardware version of the current virtual machine.

Possible version numbers are:

3: Virtual machines created with WS4.x, ESX2.x, GSX3.x, ACE1.x, and with WS5.x as a legacy VM

4: Virtual machines created with WS5.x as a new type VM

Ok, this looks about right and make sense with the VMware version string and printf combo.

We step through to confirm.

At the point where the in instruction is about to execute the lowest byte of ECX is 0x11. We read backwards through the assembly following the register assignments to confirm that it is the same 0x11 that we saw before inExecutor was called.

The return buffer pointer that was placed in ecx before entering inExecutor is populated with the register values.

Now, we can easily spot the opcode, and return values without going into inExecutor.

We get the 4 in eax for free, by having created this VM with a newer version of VMware Player. That was easy, so we press F9 to hit the next call to inExecutor.

PANW:0128906F loc_128906F:

PANW:0128906F mov [ebp+ms_exc.registration.TryLevel], 0FFFFFFFEh

PANW:01289076 xor eax, eax

PANW:01289078 mov word ptr [ebp+var_44+8], ax

PANW:0128907C xorps xmm0, xmm0

PANW:0128907F movups [ebp+var_44+0Ah], xmm0

PANW:01289083 mov [ebp+var_2A], eax

PANW:01289086 mov [ebp+var_26], ax

PANW:0128908A mov dword ptr [ebp-34h], 1

PANW:01289091 lea ecx, [ebp+var_44+8]

PANW:01289094 call inExecutor

PANW:01289099 cmp dword ptr [ebp+var_44+8], 3E8h

PANW:012890A0 ja short loc_12890AF

(Note that the image was rebased and the addresses are now different. The old image base was 0x400000, the new image base is 0x1270000. You can rebase the program to match these addresses Edit -> Segments -> Rebase program)

Opcode is 1, we look it up in the reference and it maps to processor speed. It’s a similar case where the instruction only returns a value in eax…but it doesn’t seem to matter as both branches eventually lead to the same basic block. The only difference being whether or not the binary will printf “Slow”.

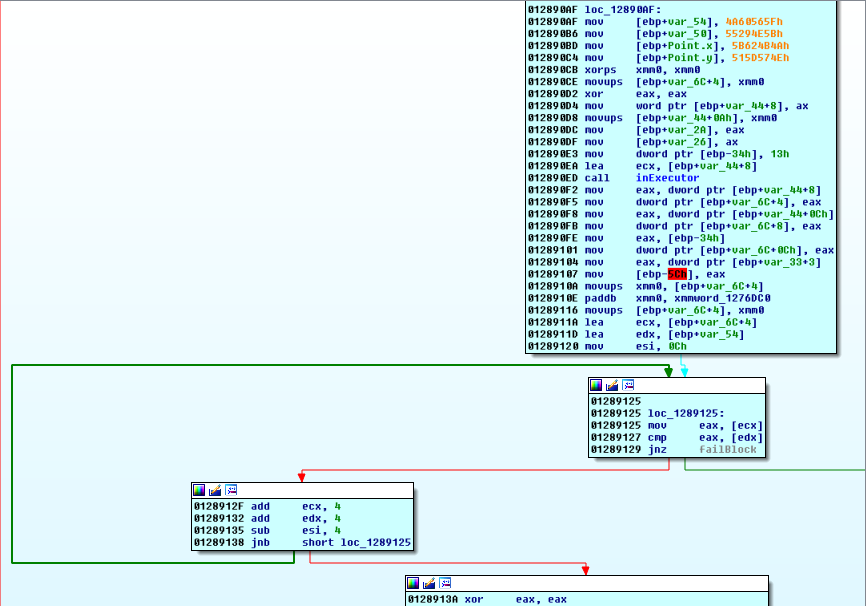

The next inExecutor call is just a few steps away and in a basic block that is less friendly:

We ignore the unfriendliness and focus on just a few things:

- opcode is 0x13

PANW:012890E3 mov dword ptr [ebp-34h], 13h PANW:012890EA lea ecx, [ebp+var_44+8] PANW:012890ED call inExecutor PANW:012890F2 mov eax, dword ptr [ebp+var_44+8] PANW:012890F5 mov dword ptr [ebp+var_6C+4], eax - The value(s) returned by opcode 0x13, are added to xmmword_1276DC0

PANW:0128910A movups xmm0, [ebp+var_6C+4] PANW:0128910E paddb xmm0, xmmword_1276DC0 PANW:01289116 movups [ebp+var_6C+4], - xmmword_1276DC0 has this value:

PANW:01276DC0 xmmword_1276DC0 xmmword 9090909090909090909090909090909h - There are two interesting buffers, esi is initialized to 0xC

PANW:0128911A lea ecx, [ebp+var_6C+4] PANW:0128911D lea edx, [ebp+var_54] PANW:01289120 mov esi, 0Ch -

the loop has two exit conditions

- this exit leads to fail…so, eax must always equal edx

PANW:01289125 mov eax, [ecx] PANW:01289127 cmp eax, [edx] PANW:01289129 jnz failBlock - this block will exit if (esi-4) < 0

PANW:0128912F add ecx, 4 PANW:01289132 add edx, 4 PANW:01289135 sub esi, 4 PANW:01289138 jnb short loc_1289125

- this exit leads to fail…so, eax must always equal edx

So, to win…we will advance our ecx and edx pointers by 4 bytes, 4 times and have them match each time

What then, are the bytes we want to match?

We could do the math at the beginning of this uglier block, or we can let the processor do it for us and just find out what is in the edx buffer right before we start our comparison loop (#4)

Since this i/o opcode returns a value in eax, ebx, ecx, and edx, it would be worth our while to examine how these are arranged in our return buffer

PANW:012890ED call inExecutor

PANW:012890F2 mov eax, dword ptr [ebp+var_44+8]

We click on the line just after the in instruction executes, and note the register values:

EAX 89344D56

EBX 5DA79959

ECX AE229E88

EDX F36911D6

opening the .vmx file for this machine in a text editor, we find the uuid for the BIOS:

uuid.bios = “56 4d 34 89 59 99 a7 5d-88 9e 22 ae d6 11 69 f3”

Ok, so it is stored as 32-bit little-endian in each of the registers.

After the inExecutor functions copies these values into the return buffer, it looks like this:

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC04 db 56h ; V

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC05 db 4Dh ; M

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC06 db 34h ; 4

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC07 db 89h ; ë

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC08 db 59h ; Y

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC09 db 99h ; Ö

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0A db 0A7h ; º

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0B db 5Dh ; ]

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0C db 88h ; ê

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0D db 9Eh ; P

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0E db 22h ; "

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0F db 0AEh ; «

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC10 db 0D6h ; +

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC11 db 11h

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC12 db 69h ; i

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC13 db 0F3h ; =

A copy of this value + xmmword_1276DC0 ends up in the var_6C buffer that is used in the comparison loop (#4)

So we run to the beginning of the comparison loop and examine the buffer we will be comparing against:

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBEC db 5Fh ; _

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBED db 56h ; V

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBEE db 60h ; `

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBEF db 4Ah ; J

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF0 db 5Bh ; [

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF1 db 4Eh ; N

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF2 db 29h ; )

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF3 db 55h ; U

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF4 db 4Ah ; J

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF5 db 4Bh ; K

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF6 db 62h ; b

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF7 db 5Bh ; [

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF8 db 4Eh ; N

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBF9 db 57h ; W

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBFA db 5Dh ; ]

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBFB db 51h ; Q

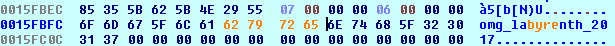

We can quickly calculate what our BIOS uuid should have been to end up with this buffer:

>>> b = 0x9090909090909090909090909090909

>>> c = 0x5f56604a5b4e29554a4b625b4e575d51

>>> hex(c-b)

'0x564d57415245204c41425952454e5448L'

>>> d = c-b

>>> d

114715184240537367128919208042550940744L

alright, let’s just do a quick hacky solution and pack these into a string 8 bytes at a time

>>> e = 0x564d57415245204c

>>> f = 0x41425952454e5448

>>> import struct

>>> struct.pack('>q', e)

'VMWARE L'

>>> struct.pack('>q', f)

'ABYRENTH'

>>>

Good to know…but, rather than restart our debugging run to change the BIOS uuid for our VM…we can just edit the bytes in our buffer to match the buffer that edx is pointing to.

This RE stack exchange post has a nice way to do just that

def PatchArr(dest, str):

for i, c in enumerate(str):

idc.PatchByte(dest+i, ord(c));

# usage: patchArr(start address, string of bytes to write)

copyBuff = GetManyBytes(0x15FBEC, 0x10)

PatchArr(0x15FC04, copyBuff)

RefreshDebuggerMemory()

The surgery was a success, we carry on.

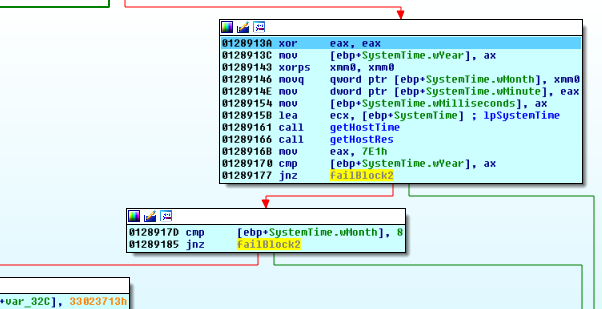

IDA helps us out again, and after examining the opcodes for the next two functions that call inExecutor, we go ahead and set the host month to August

It’s not immediately obvious what the host resolution is being used for, if anything at all.

so…whatever…

We press a lot of F8 to step over.

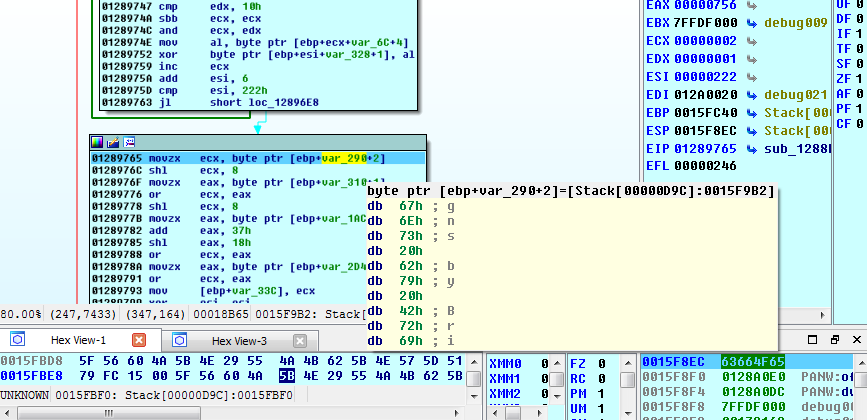

We scroll down past what looks like a stack string being decrypted, and examine the buffer that results:

Scrolling to the beginning of the buffer, and pressing a, we get a paragraph about the movie Labyrinth. A quick google search reveals that it was taken from the wikipedia page about the movie. That’s something to keep in mind, I guess.

We F8 some more, and find the next function that calls inExecutor:

PANW:012897C2 E8 89 F3 FF FF call sub_1288B50

PANW:012897C7 8D 45 B4 lea eax, [ebp+Point]

PANW:012897CA 50 push eax ; lpPoint

PANW:012897CB FF 15 20 31 29+call ds:GetCursorPos

PANW:012897D1 85 F6 test esi, esi

PANW:012897D3 75 42 jnz short loc_1289817

We take a look inside:

PANW:01288B50 push ebp

PANW:01288B51 mov ebp, esp

PANW:01288B53 and esp, 0FFFFFFF8h

PANW:01288B56 sub esp, 18h

PANW:01288B59 xor eax, eax

PANW:01288B5B lea ecx, [esp+18h+var_18]

PANW:01288B5E mov word ptr [esp+18h+var_18], ax

PANW:01288B62 xorps xmm0, xmm0

PANW:01288B65 mov [esp+18h+var_6], eax

PANW:01288B69 mov [esp+18h+var_2], ax

PANW:01288B6E mov eax, 4

PANW:01288B73 movups xmmword ptr [esp+18h+var_18+2], xmm0

PANW:01288B78 mov [esp+8], ax

PANW:01288B7D call inExecutor

PANW:01288B82 mov eax, [esp+18h+var_18]

PANW:01288B85 movzx edx, word ptr [esp+18h+var_18]

PANW:01288B89 shr eax, 10h

PANW:01288B8C mov esp, ebp

PANW:01288B8E pop ebp

PANW:01288B8F retn

Opcode 4, mouse cursor position. When we return from here, it is followed by a GetCursorPos call.

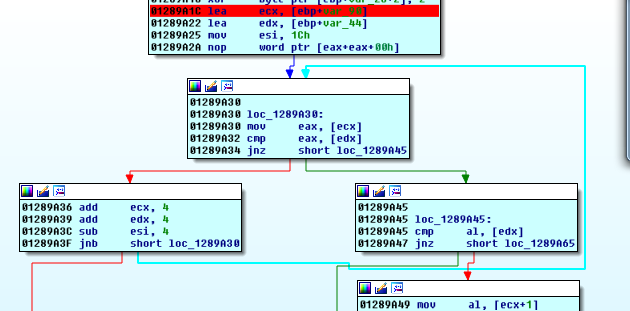

It also looks like we are stuck in this mouse cursor loop until we satisfy whatever requirement this is

PANW:012897D5 mov ecx, [ebp+Point.y]

PANW:012897D8 mov eax, ecx

PANW:012897DA sub eax, [ebp+var_334]

PANW:012897E0 sub eax, [ebp+var_104]

PANW:012897E6 mov edx, [ebp+Point.x]

PANW:012897E9 mov [ebp+var_334], edx

PANW:012897EF add eax, edx

PANW:012897F1 xor edx, edx

PANW:012897F3 cmp eax, 0Dh

PANW:012897F6 mov eax, 0Dh

PANW:012897FB cmovz edx, eax

PANW:012897FE mov [ebp+var_104], ecx

PANW:01289804 test edx, edx

PANW:01289806 jz short loc_12897C2

So we need the zero flag to NOT be set -> so edx must not be 0 -> edx is zeroed every time, and only overwritten with the cmovz edx, eax -> that only happens if eax is equal to 0xD

eax is:

cursorYpos - var_334 - var_104 + cursorXpos

var_334 and var_104 came from the block just before the loop, and were given a freshly xor’d esi

After doing their part in the calculations, 334 then takes on cursorXpos and 104 takes on cursorYpos.

So, we could meet this condition on the first time through this loop: cursorYpos + cursorXpos == 0xD

We change the Point.y value and Point.x value returned from GetCursorPos to 0x6 and 0x7 (or anything else that’ll sum to 0xD) and we are released from our cursor position jail…

It is interesting that we didn’t use the result from the in instruction, we will probably pay for this later, but for now…F9.

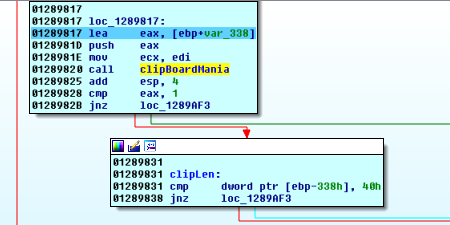

We hit the next function that calls inExecutor. Using the same strategy, we spot the opcodes, and look at the surrounding code to see that this function is going to grab the text in the clipboard, and the length of that text

PANW:01288BC9 mov eax, 6

PANW:01288BCE mov [esp+28h+var_10], ax

PANW:01288BD3 call inExecutor

PANW:01288BD8 mov edi, [esp+28h+clipConts]

PANW:01288BDC mov [esp+28h+clipBoardTxtLen], edi

PANW:01288BF6 mov eax, 7

PANW:01288BFB lea ecx, [esp+28h+clipConts]

PANW:01288BFF mov [esp+28h+var_10], ax

PANW:01288C04 call inExecutor

PANW:01288C09 mov eax, [esp+28h+clipConts]

PANW:01288C3F mov eax, [ebp+arg_0]

PANW:01288C42 mov byte ptr [edi+ebx], 0

PANW:01288C46 mov [eax], edi

Doing a bit of tracking of what goes in and comes out, we see that the clipboard must have 0x40 bytes in it. Otherwise, we end up looping back to the cursor position game.

We go ahead and satisfy the length requirement at least, and see if something recognizeable happens to our buffer…hopefully something simple.

some super hacky python:

>>> startChar = 0x41

>>> stringThing = []

>>> for c in range(0x10):

... aList = [startChar] * 4

... aList = ''.join(map(chr,aList))

... stringThing.append(aList)

... startChar += 1

...

>>> stringThing

['AAAA', 'BBBB', 'CCCC', 'DDDD', 'EEEE', 'FFFF', 'GGGG', 'HHHH', 'IIII', 'JJJJ', 'KKKK', 'LLLL', 'MMMM', 'NNNN', 'OOOO', 'PPPP']

>>> ''.join(stringThing)

'AAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHHIIIIJJJJKKKKLLLLMMMMNNNNOOOOPPPP'

>>> stringThing = ''.join(stringThing)

>>> len(stringThing)

64

>>>

Now we have recognizeable clipboard contents that’ll allow us to see if some simple operations were performed.

Knowing that we are in a loop that’ll send us back to the cursor position section at worst, we can move quickly until we end up at another loop that compares two buffers:

The logic looks quite familiar to the bios uuid checking logic, let’s apply the same strategy.

Our AABB blah buffer does look a little interesting, but perhaps our buffer copying trick can circumvent the need to calculate the proper input.

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB0 db 0B1h ; ¦

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB1 db 0B1h ; ¦

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB2 db 0C2h ; -

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB3 db 0C2h ; -

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB4 db 0D3h ; +

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB5 db 0D3h ; +

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB6 db 0E4h ; S

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB7 db 0E4h ; S

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB8 db 0F5h ; )

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBB9 db 0F5h ; )

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBBA db 6

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBBB db 6

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBBC db 7

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBBD db 7

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBBE db 7

We can go back and do the math if our buffer copy experiment doesn’t work out.

The target buffer:

0015FBFC 51 68 79 6C 7B 6F 33 27 70 75 27 6F 70 7A 27 76 Qhyl{o3'pu'opz'v

0015FC0C 7E 73 27 6D 76 79 74 33 27 7E 68 7B 6A 6F 6C 7A ~s'mvyt3'~h{jolz

0015FC1C 32 30 31 37 00 FC 15 00 65 4F 66 63 EC F8 15 00 2017.n..eOfc8°..

0015FC2C 00 00 00 00 7C FC 15 00 C0 97 27 01 85 35 5B 62 ....|n..+ù'.à5[b

We copy the target buffer to our buffer, and keep stepping. After the comparison loop, we see that we are now in the block that’ll call the flag checking routine:

PANW:01289A72 xorps xmm0, xmm0

PANW:01289A75 movups [ebp+var_44+1], xmm0

PANW:01289A79 movq [ebp+anonymous_0+1], xmm0

PANW:01289A7E mov [ebp-2Bh], eax

PANW:01289A81 mov word ptr [ebp+anonymous_1+5], ax

PANW:01289A85 mov byte ptr [ebp+anonymous_1+7], al

PANW:01289A88 mov eax, [ebp+var_33C]

PANW:01289A8E mov dword ptr [ebp+var_44], eax

PANW:01289A91 mov eax, [ebp+var_330]

PANW:01289A97 mov dword ptr [ebp+var_44+4], eax

PANW:01289A9A mov eax, [ebp+var_108]

PANW:01289AA0 mov dword ptr [ebp+var_44+6], eax

PANW:01289AA3 mov eax, [ebp+var_340]

PANW:01289AA9 mov dword ptr [ebp+var_44+0Ah], eax

PANW:01289AAC movsx ecx, byte ptr [ebp+var_23+2]

PANW:01289AB0 shl ecx, 8

PANW:01289AB3 movsx eax, byte ptr [ebp+var_23+1]

PANW:01289AB7 or ecx, eax

PANW:01289AB9 shl ecx, 8

PANW:01289ABC movsx eax, byte ptr [ebp+var_23]

PANW:01289AC0 or ecx, eax

PANW:01289AC2 shl ecx, 8

PANW:01289AC5 movsx eax, [ebp+var_24]

PANW:01289AC9 or ecx, eax

PANW:01289ACB mov dword ptr [ebp+var_44+0Eh], ecx

PANW:01289ACE lea ecx, [ebp+var_44]

PANW:01289AD1 call flagRoutine

PANW:01289AD6

PANW:01289AD6 loc_1289AD6:

PANW:01289AD6 test al, al

PANW:01289AD8 jnz loc_1289068

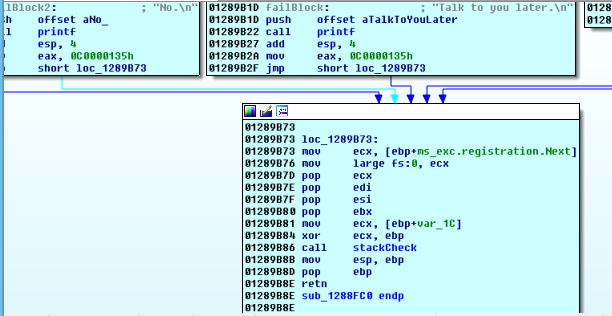

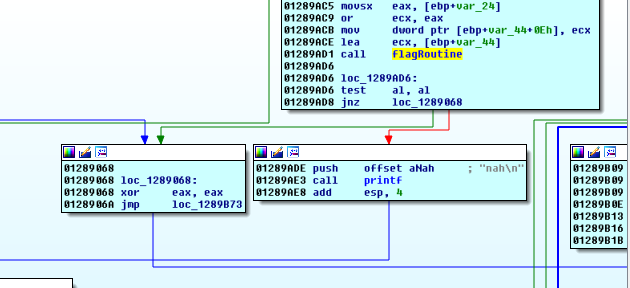

So, we look ahead to see how we can win

here is the basic block that’ll release us from this IN hell

We have already passed by the other blocks whose edges can lead to this exit, except for 0x1289068:

So, we need something other than 0 in al to reach the only winning exit block. Presumably, the function (that we’ve labeled flagRoutine from our initial recon using the strings xref) will set that proper al value if our buffer was correct.

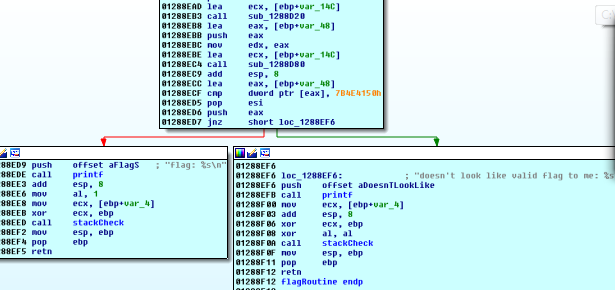

Taking a quick look inside that function, we see that the winning path does give us a non-zero al:

Ok…so we run to the line right before the flag routine is called:

PANW:01289ACE lea ecx, [ebp+var_44]

PANW:01289AD1 call flagRoutine

to examine the contents of the var_44 buffer passed into the flagRoutine:

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBFC db 6Fh ; o

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBFD db 6Dh ; m

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBFE db 67h ; g

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FBFF db 5Fh ; _

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC00 db 6Ch ; l

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC01 db 61h ; a

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC02 db 8Ah ; è

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC03 db 7Ah ; z

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC04 db 0Fh

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC05 db 0F7h ; ˜

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC06 db 6Eh ; n

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC07 db 74h ; t

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC08 db 68h ; h

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC09 db 5Fh ; _

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0A db 32h ; 2

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0B db 30h ; 0

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0C db 31h ; 1

Stack[00000D9C]:0015FC0D db 37h ; 7

We definitely overlooked something somewhere, but this is too close to be coincidence. We change this buffer to the most likely candidate: omg_labyrenth_2017

>>> hex(struct.unpack('>I', "byre")[0])

'0x62797265'

(big endian for ease of data entry)

a little hex-dump F2 magic:

We set a break point inside of the flagRoutine:

PANW:01288ED9 push offset aFlagS ; "flag: %s\n"

PANW:01288EDE call printf

Examining the arguments to printf, we see our flag:

Stack[00000AFC]:0016F3E4 aPanVmwareLabyrenth db 'PAN{VMWare Labyrenth 2017 Challenge. VMWare Backdoor API is nice.'

Stack[00000AFC]:0016F3E4 db '}',0

This was a particularly sloppy approach, but we get all the low-hanging fruit we can and save energy/time for the situations which demand some more care.