Level 4: labyrenth

Description:

You walk to the west...

A goblin hands you a challenge and an apple, you stand frozen until you solve the

challenge.

7z Download

7z Password: labyrenth

Hint: Send me this identifier together with your $$$$ to decrypt your file:

da91e949f4c2e814f811fbadb3c195b8

Author(s): Erye Hernandez, Amro Younes, Zhi Xu

http://dl.labyrenth.com/osxransomware/fb450f0eb3cb0b1466692152d99163fb3cd1efca68529244fb679b74da96b9e8.7z

Alternate binary download link

Step 0: Hints

We note the identifier generated by the ransomware that we’re about to analyze, and that’s about all we can do with that hint.

Step 1: Initial triage and recon

$ file labyrenth

labyrenth: Mach-O 64-bit x86_64 executable, flags:<NOUNDEFS|DYLDLINK|TWOLEVEL|PIE>

and some selected $ strings output:

%02x%02x%02x%02x%02x%02x

Send me this identifier together with your $$$$ to derypt your file:

ioreg -l | grep -e Manufacturer -e 'Vendor Name' | grep -e 'Parallels' -e VMware -e Fusion -e 'Virtual Box'

Error opening pipe!

Command not found or exited with error status

.encrypted

PANW_Top_Secret_Sauce.jpg

%s/%s

%02x

IOEthernetInterface

IOPrimaryInterface

IOPropertyMatch

IOService

IOMACAddress

_CC_MD5_Final

_CC_MD5_Init

_CC_MD5_Update

Some stuff about MD5, MAC addresses, and ioreg

The file we have is PANW_Top_Secret_Sauce.jpg.encrypted and it looks like this binary simply adds the .encrypted extension. It also references the original jpg.

We might as well go on a renaming/string xref spree and confirm/form some more ideas about what’s going on.

This might not hurt too much…the binary is only 25kb.

We start with the “Send me this identifier” string”

__text:0000000100000B6D mov [rbp+var_448], rax

__text:0000000100000B74 mov rax, [rbp+var_448]

__text:0000000100000B7B mov rdi, rax

__text:0000000100000B7E call _oohbfhwebabje

__text:0000000100000B83 lea rdi, aSendMeThisIden ; "Send me this identifier together with y"...

__text:0000000100000B8A mov [rbp+var_468], rax

__text:0000000100000B91 mov rsi, [rbp+var_468]

__text:0000000100000B98 mov al, 0

__text:0000000100000B9A call _printf

__text:0000000100000B9F mov [rbp+var_434], 0

Let’s make sure we understand the calling convention before we make any more assumptions.

The OS X x86-64 function calling conventions are the same as the function calling conventions described in System V Application Binary Interface AMD64 Architecture Processor Supplement.

and the wikipedia/google combo for x86-64 calling convention gives us some answers:

The first six integer or pointer arguments are passed in registers RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX (R10 in the Linux kernel interface), R8, and R9, while XMM0, XMM1, XMM2, XMM3, XMM4, XMM5, XMM6 and XMM7 are used for certain floating point arguments. As in the Microsoft x64 calling convention, additional arguments are passed on the stack and the return value is stored in RAX and RDX.

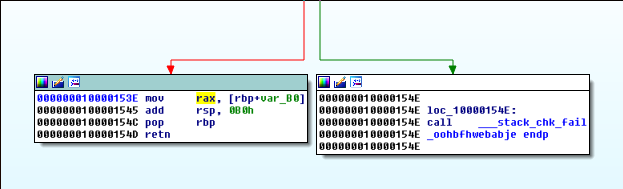

We take a quick look inside _oohbf blah and make sure it is setting the return value (RAX).

Skimming through the function, it looks like MD5 is being used to generate the the identifier it returns. We rename it idGeneratorMD5.

That sounds a bit odd, but maybe the attacker has a large dictionary of MD5 hashes to encryption keys.

We keep this in mind, but don’t spend too much time on it. Perhaps just a quick check to identify it:

Your hash may be one of the following :

- MD5

- NTLM

- MD4

- LM

- RAdmin v2.x

- Haval-128

- MD2

- RipeMD-128

- Tiger-128

- Snefru-128

- MD5(HMAC)

...

and a lookup:

da91e949f4c2e814f811fbadb3c195b8 Unknown Not found.

It was worth a shot!

Press esc to go back until we are in main again, we continue the strings/xref renaming game without diving too deeply into anything yet.

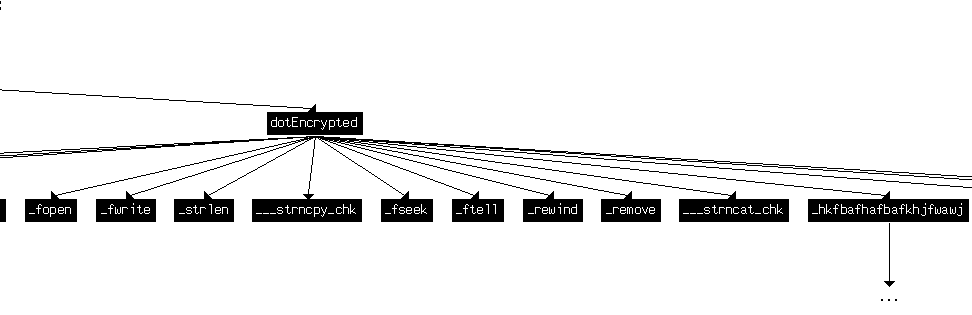

We generate a User xrefs chart like we did in the Level 1 writeup (View -> Graphs -> User xrefs chart) to see if things make a little bit of sense now.

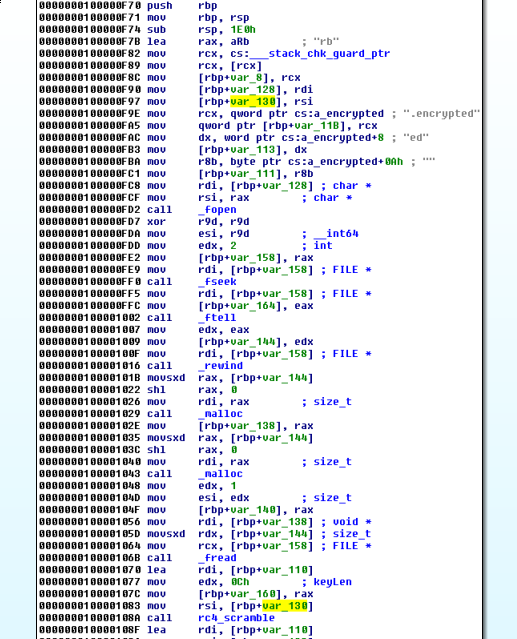

Unfortunately, the library functions are not highlighted in a different color so we spend a few extra cycles processing that. But it does make things clear for the function that uses the “.encrypted” string:

This is likely going to encrypt a file, and we should investigate the functions used here that were not caught by our strings/xref game:

__text:000000010000106B call _fread

__text:0000000100001070 lea rdi, [rbp+var_110]

__text:0000000100001077 mov edx, 0Ch

__text:000000010000107C mov [rbp+var_160], rax

__text:0000000100001083 mov rsi, [rbp+var_130]

__text:000000010000108A call _hkfbafhafbafkhjfwawj

__text:000000010000108F lea rdi, [rbp+var_110]

__text:0000000100001096 mov rsi, [rbp+var_138]

__text:000000010000109D mov rdx, [rbp+var_140]

__text:00000001000010A4 mov ecx, [rbp+var_144]

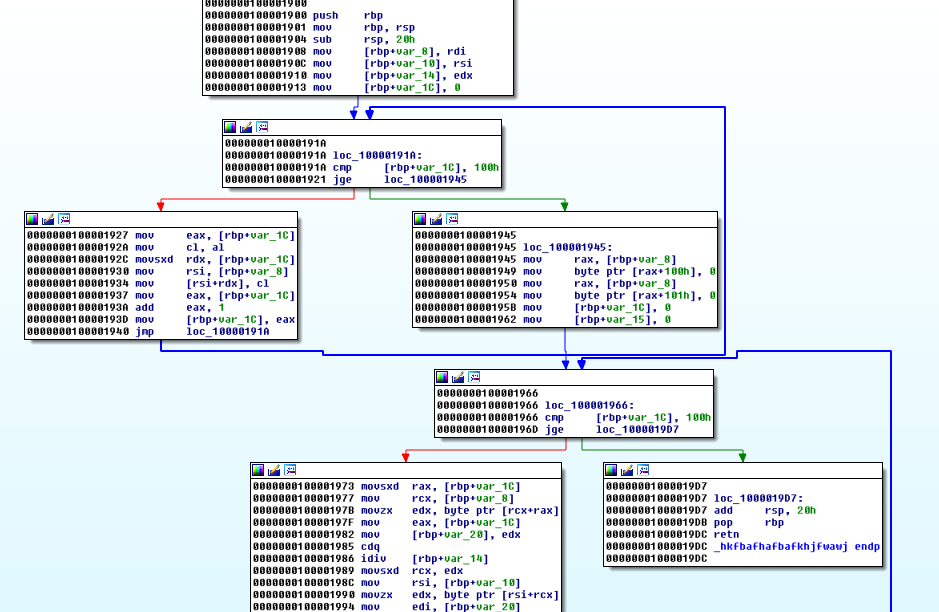

We look inside _hkf and it’s Good News, Everyone! Having reversed this algorithm once or twice before (or three times? I might be slow), it starts to look familiar.

We will detour to read a different post for a moment, as I will not attempt to explain this any better than what has been covered in this excellent post:

An Introduction to Recognizing and Decoding RC4 Encryption in Malware

It’s also quite possible to step through and translate the assembly to python and unknowingly re-implement this algorithm. I’ve definitely done that at least twice.

We rename this function rc4_scramble and take note of this function at the bottom:

__text:00000001000019B7 mov r9, [rbp+var_8]

__text:00000001000019BB add r9, rcx

__text:00000001000019BE mov rdi, rsi

__text:00000001000019C1 mov rsi, r9

__text:00000001000019C4 call _bfuahwaeriashk

__text:00000001000019C9 mov eax, [rbp+var_1C]

__text:00000001000019CC add eax, 1

__text:00000001000019CF mov [rbp+var_1C], eax

__text:00000001000019D2 jmp loc_100001966

it has a cross reference inside of another function we missed during the renaming. We study it:

__text:00000001000019E0 push rbp

__text:00000001000019E1 mov rbp, rsp

__text:00000001000019E4 mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

__text:00000001000019E8 mov [rbp+var_10], rsi

__text:00000001000019EC mov rsi, [rbp+var_8]

__text:00000001000019F0 mov al, [rsi]

__text:00000001000019F2 mov [rbp+var_11], al

__text:00000001000019F5 mov rsi, [rbp+var_10]

__text:00000001000019F9 mov al, [rsi]

__text:00000001000019FB mov rsi, [rbp+var_8]

__text:00000001000019FF mov [rsi], al

__text:0000000100001A01 mov al, [rbp+var_11]

__text:0000000100001A04 mov rsi, [rbp+var_10]

__text:0000000100001A08 mov [rsi], al

__text:0000000100001A0A pop rbp

__text:0000000100001A0B retn

and see that it just swaps two values. We rename it accordingly.

The other function that uses it is the rc4 encrypting loop.

__text:000000010000108A call rc4_scramble

__text:000000010000108F lea rdi, [rbp+var_110]

__text:0000000100001096 mov rsi, [rbp+var_138]

__text:000000010000109D mov rdx, [rbp+var_140]

__text:00000001000010A4 mov ecx, [rbp+var_144]

__text:00000001000010AA call rc4_crypt

Knowing that our file is RC4 encrypted, we turn our attention to recovering the key.

We examine the arguments to the rc4_scramble function:

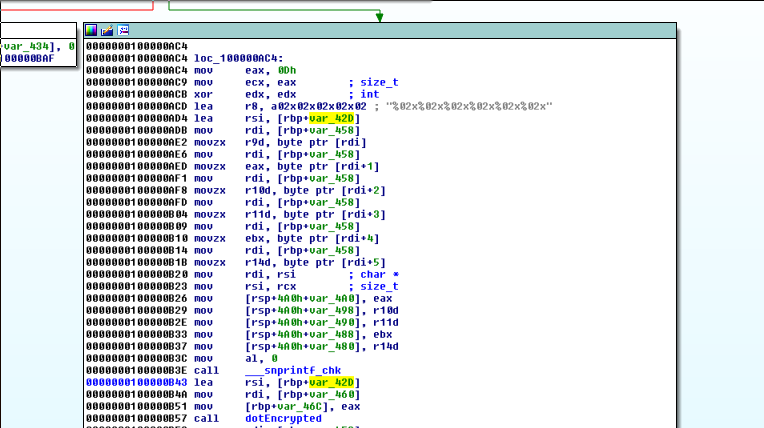

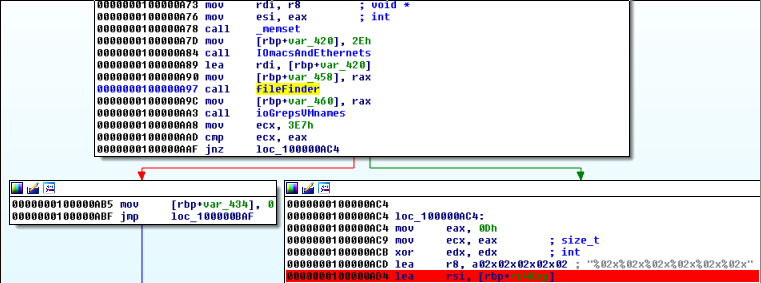

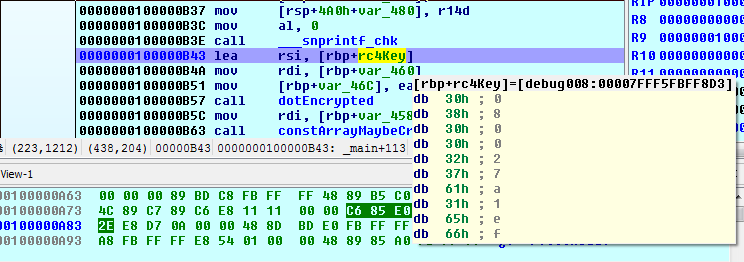

We trace the key back to main:

We set breakpoints here:

__text:0000000100000ACD lea r8, a02x02x02x02x02 ; "%02x%02x%02x%02x%02x%02x"

__text:0000000100000AD4 lea rsi, [rbp+rc4Key]

and here

__text:0000000100000B3E call ___snprintf_chk

__text:0000000100000B43 lea rsi, [rbp+rc4Key]

__text:0000000100000B4A mov rdi, [rbp+var_460]

__text:0000000100000B51 mov [rbp+var_46C], eax

__text:0000000100000B57 call dotEncrypted

We go to the top of main and work our way forwards to this point.

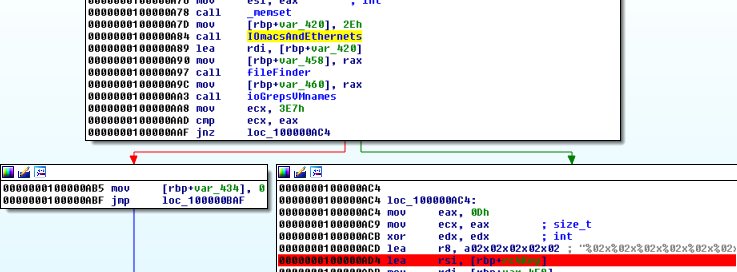

Based on the library calls that the functions inside of IOmacsandEthernets are making, we assume that this function will return the MAC address for the primary ethernet adapter. We’ll double-check dynamically in a little while, but for now we move on to fileFinder:

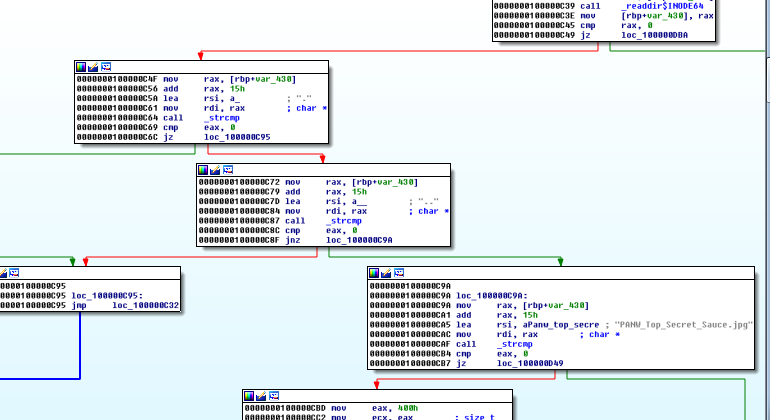

It looks like this binary is expecting to find the file PANW_Top_Secret_Sauce.jpg

So we rename our encrypted file and place it in the directory from which we will run this binary. If we have the right key, then the RC4 encryption will actually decrypt our file too.

We go back to main and go into ioGrepsVMnames

It looks like it runs a command:

ioreg -l | grep -e Manufacturer -e 'Vendor Name' | grep -e 'Parallels' -e VMware -e Fusion -e 'Virtual Box'

then sets a couple of flags if that was succesful:

__text:0000000100000F2B mov [rbp+var_C], 0

__text:0000000100000F32 mov [rbp+var_2C], 1

as long as we avoid this flag:

__text:0000000100000EE2 mov [rbp+var_C], 3E7h

__text:0000000100000EE9 mov [rbp+var_2C], 1

__text:0000000100000EF0 jmp loc_100000F39

then main will branch to the rc4 encryption.

Step 2: Dynamic Analysis

Ok, we are ready for dynamic analysis.

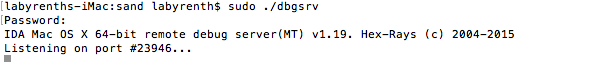

- Copy the mac_serverx64 debugging server to the target machine.

- Copy the labyrenth binary

- Copy the PANW jpg (renamed to drop the .encrypted extension).

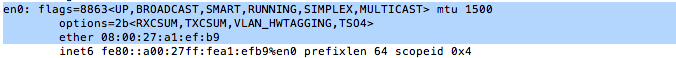

- Find the ip address of the OSX machine

- Note the MAC address of the primary ethernet interface

- Start the debug server

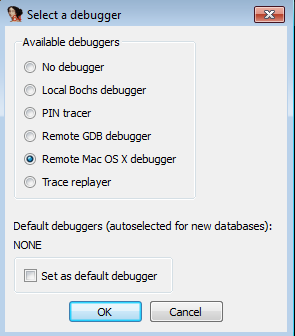

- Select remote debugger

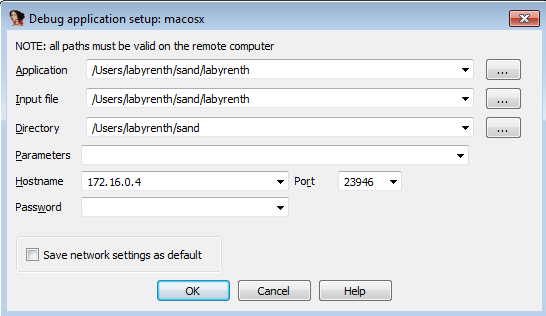

- Set the process options on the analysis machine

You might get some errors when connecting, or complaints…just click a bunch of Ok and Apply until they go away.

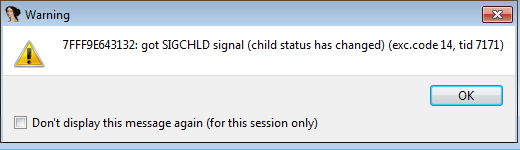

Trying to get to our first key breakpoint, we hit a SIGCHLD along the way.

It’s probably because IDA can’t debug multiple processes. No matter, we acknowledge the warning, then press esc to see where the warning was triggered. We set a breakpoint on the jump, in case we need to change the branch.

Press ctrl+f7 to run until return, until we are back in that function.

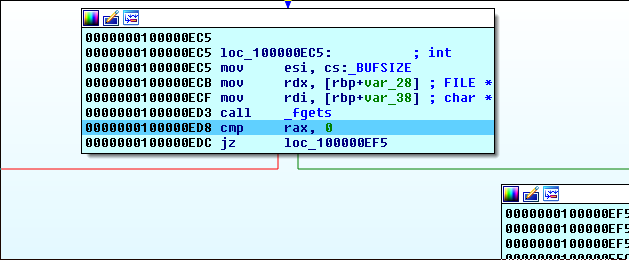

Things look fine, we F8 until we reach our rc4Key breakpoint. It has yet to be populated, so we press F9 to hit the next rc4Key breakpoint.

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8D3 db 30h ; 0

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8D4 db 38h ; 8

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8D5 db 30h ; 0

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8D6 db 30h ; 0

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8D7 db 32h ; 2

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8D8 db 37h ; 7

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8D9 db 61h ; a

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8DA db 31h ; 1

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8DB db 65h ; e

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8DC db 66h ; f

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8DD db 62h ; b

debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8DE db 39h ; 9

So the rc4 key is the MAC address of our primary ethernet interface, formatted to exclude the colons, and each digit converted to its ascii byte.

We need a way to link the identifier to the MAC address in order to decrypt the file we’ve been given.

__text:0000000100000B3E call ___snprintf_chk

__text:0000000100000B43 lea rsi, [rbp+rc4Key]

__text:0000000100000B4A mov rdi, [rbp+var_460]

__text:0000000100000B51 mov [rbp+var_46C], eax

__text:0000000100000B57 call dotEncrypted

__text:0000000100000B5C mov rdi, [rbp+var_458]

__text:0000000100000B63 call constArrayMaybeCrypto

__text:0000000100000B68 mov esi, 14h

__text:0000000100000B6D mov [rbp+var_448], rax

__text:0000000100000B74 mov rax, [rbp+var_448]

__text:0000000100000B7B mov rdi, rax

__text:0000000100000B7E call idGeneratorMD5

__text:0000000100000B83 lea rdi, aSendMeThisIden ; "Send me this identifier together with y"...

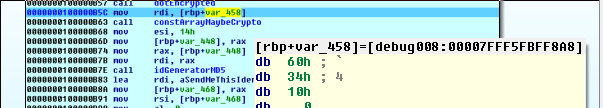

We step over the dotEncrypted function and look at the argument to the constArrayMaybeCrypto function (named for its used of a constant array 0x100001289, and nested loops with a bunch of math).

The argument looks like a pointer:

We double click on var_458, and cycle through the data carousel (pressing d) until we get a quad word (dq):

00007FFF5FBFF8A8 dq offset unk_100103460

double clicking this location, we get:

debug050:0000000100103460 unk_100103460 db 8 ; DATA XREF: debug008:00007FFF5FBFF8A8o

debug050:0000000100103461 db 0

debug050:0000000100103462 db 27h ; '

debug050:0000000100103463 db 0A1h ; í

debug050:0000000100103464 db 0EFh ; n

debug050:0000000100103465 db 0B9h ; ¦

debug050:0000000100103466 db 0

it is another form of our MAC address, using each digit as a number rather than ascii (e.g., 8 is 0x8 and not 0x38)

Using the same strategy as we did for the identifier, we see that the argument to idGeneratorMD5 is actually the return value from constArrayMaybeCrypto.

So the MAC address and constArray are combined into something that will be MD5 hashed to create the identifier.

We will focus our efforts on reversing this maybeCrypto hash. Once we are able to generate the same hash as this function, we will MD5 it to see if it matches the identifier that idGeneratorMD5 returns. This will eliminate the need to analyze that function.

We’ll deal with the difficulty in recovering a MAC address from an MD5 hash of a hash afterwards. First, we need to be able to generate the same maybeCrypto hash.

We step inside constArrayMaybeCrypto:

__text:0000000100001270 push rbp

__text:0000000100001271 mov rbp, rsp

__text:0000000100001274 sub rsp, 0B0h

__text:000000010000127B mov eax, 4

__text:0000000100001280 mov ecx, eax

__text:0000000100001282 mov eax, 5

__text:0000000100001287 mov esi, eax

__text:0000000100001289 lea rdx, someConstArray

__text:0000000100001290 mov eax, 64h

__text:0000000100001295 mov r8d, eax

__text:0000000100001298 lea r9, [rbp+var_70]

__text:000000010000129C mov r10, cs:___stack_chk_guard_ptr

__text:00000001000012A3 mov r10, [r10]

__text:00000001000012A6 mov [rbp+var_8], r10

__text:00000001000012AA mov [rbp+var_78], rdi

__text:00000001000012AE mov rdi, r9 ; void *

__text:00000001000012B1 mov [rbp+var_90], rsi

We rename rbp+var_78 to macAddr, rdi is overwritten immediately afterwards so we don’t have to worry about tracking other places our MAC address is used.

Checking the xrefs on this macAddr variable, it looks quite good. It is only written once (the initial assignment), and it is read only once as well.

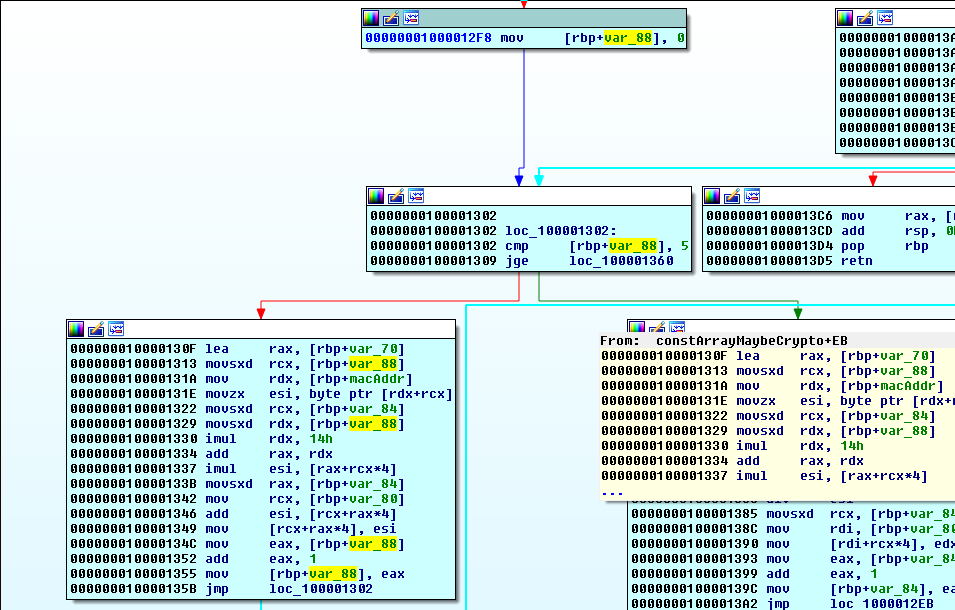

It is read in the inner loop of this function. We look at this loop’s counter var_88 (rename to innerCounter):

It is initialized to 0:

00000001000012F8 mov [rbp+innerCounter], 0

It exits when it has reached the value 5:

__text:0000000100001302 loc_100001302:

__text:0000000100001302 cmp [rbp+innerCounter], 5

__text:0000000100001309 jge loc_100001360

Note the JGE. It is checked before any of the loop’s body executes. So we will only loop 5 times since the loop counter increments by 1:

__text:000000010000134C mov eax, [rbp+innerCounter]

__text:0000000100001352 add eax, 1

__text:0000000100001355 mov [rbp+innerCounter], eax

__text:000000010000135B jmp loc_100001302

This is Good News, Everyone because:

__text:0000000100001313 movsxd rcx, [rbp+innerCounter]

__text:000000010000131A mov rdx, [rbp+macAddr]

__text:000000010000131E movzx esi, byte ptr [rdx+rcx]

The only place where the macAddr is read, will be indexed using this counter.

That reduces our MAC address search space by 1 byte. Only 5 bytes of the MAC address are used in computing this hash, and therefore the identifier.

We take the constArray and save it to a file

Python>open(‘constArray’, ‘wb’).write(GetManyBytes(0x100001F40, 0x64))

Before we translate this algorithm by hand to a python script, let’s just run this thing, see what comes out:

For this particular MAC address, we get:

Python>list(GetManyBytes(0x100400420, 0x14)) [‘\x1d’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘$’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\xcb’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\xd6’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x1b’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’, ‘\x00’]

0x14 was deduced from the size of the first few elements

>>> import md5

>>> guess = ['\x1d', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '$', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '\xcb', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '\xd6', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '\x1b', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00']

>>> guessString = ''.join(guess)

>>> md5.new(guessString).hexdigest()

'2acac5be475f7f80d15c18c96465c54c'

and after idGeneratorMD5 runs we get:

00100400440 a2acac5be475f7f80d15c db '2acac5be475f7f80d15c18c96465c54c',0

Ok, so now we can confidently focus on just this one intermediate hash.

Line by line, we translate to python, and we arrive at this:

#!/usr/bin/env python

constArray = bytearray(open('constArray', 'rb').read())

mac = [8,0,0x27,0xa1,0xef,0xb9]

new5 = [0,0,0,0,0]

for outer in range(5):

for inner in range(5):

new5[outer] = new5[outer] + (constArray[(inner*20 + outer*4)] * mac[inner])

new5[outer] %= 0xFB

guess = [new5[0],0,0,0,new5[1],0,0,0,new5[2],0,0,0,new5[3],0,0,0,new5[4],0,0,0]

print map(chr, guess)

I know…I know, but it does work:

$ ./hashGen.py

['\x1d', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '$', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '\xcb', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '\xd6', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00', '\x1b', '\x00', '\x00', '\x00']

So…now we need to find a MAC address that hashes to some mystery hash…that MD5 hashes to da91e949f4c2e814f811fbadb3c195b8

Ok…

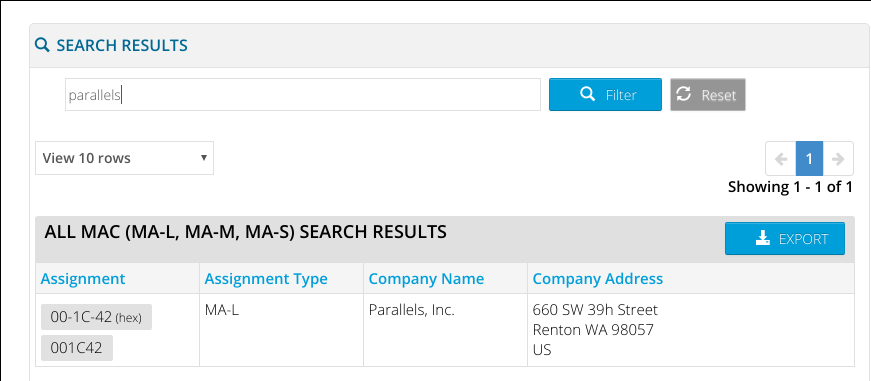

Well, this part took a little bit of a logical leap to think of what the possible search space could be. This malware runs on OSX, so it would be reasonable to assume that the MAC address was likely one that is registered by Apple.

I went down this path, and it was a dead end. However, the general concept was good.

Once I clued in to the ioreg/grep combo, and reduced the search space to the first 3 bytes of MAC address that are registered by VMware, Oracle, and Parallels, I ended up with a bruteforce script that only had to find 2 bytes. This is quite doable.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import md5

theMacs = []

theMacs.append("00A19B")

theMacs.append("001c42")

theMacs.append("001c14")

theMacs.append("000c29")

theMacs.append("005056")

theMacs.append("000569")

theMacs.append("000017")

theMacs.append("080027")

theMacs.append("080020")

theMacs.append("000F4B")

theMacs.append("0003BA")

theMacs.append("00007D")

theMacs.append("002128")

theMacs.append("0021F6")

theMacs.append("0010E0")

theMacs.append("00144F")

theMacs.append("001397")

theMacs.append("00A0A4")

theMacs.append("2CC260")

theMacs.append("00104F")

theMacs.append("000782")

theMacs.append("0020F2")

theMacs.append("00015D")

macBytes = []

for mac in theMacs:

macByte = [mac[i:i+2] for i in range(0, len(mac), 2)]

macBytes.append((ord(macByte[0].decode('hex'))))

macBytes.append((ord(macByte[1].decode('hex'))))

macBytes.append((ord(macByte[2].decode('hex'))))

constArray = bytearray(open('constArray', 'rb').read())

def ohMyGod(onceAgain):

return macBytes[onceAgain*3+0], macBytes[onceAgain*3+1], macBytes[onceAgain*3+2]

def generateMacHash(c, a, b):

here, i, go = ohMyGod(c)

mac = [here, i, go, a, b, 0] # last 0 has no meaning, it is not used

new5 = [0,0,0,0,0]

for outer in range(5):

for inner in range(5):

new5[outer] = new5[outer] + (constArray[(inner*20 + outer*4)] * mac[inner])

new5[outer] %= 0xFB

return new5

winningPrefixes = []

for c in range(len(theMacs)):

print "%d: %s" % (c, theMacs[c])

for a in range(0x100):

for b in range(0x100):

idSeed = generateMacHash(c, a, b)

guess = [idSeed[0],0,0,0,idSeed[1],0,0,0,idSeed[2],0,0,0,idSeed[3],0,0,0,idSeed[4],0,0,0,]

guess = map(chr, guess)

guessString = ''.join(guess)

result = md5.new(guessString).hexdigest()

#target = "2acac5be475f7f80d15c18c96465c54c"

target = "da91e949f4c2e814f811fbadb3c195b8"

if result == target:

print "got it!"

print "a: %s\nb: %s\n" % (hex(a), hex(b))

winningPrefixes.append(c)

print winningPrefixes

Parallels, it is:

1: 001c42

got it!

a: 0x92

b: 0xdf

Ok, so we have most of the key/MAC address. The problem is, even though using only 5 bytes to generate the identifier is great for finding this intermediate hash. We still don’t know what the 6th byte of the MAC address is, that leaves us with 256 possible keys used to encrypt the jpg.

We’ll implement the RC4 algorithm and try all 256 possible keys on our encrypted jpg. One of the resulting files will be the original jpg.

That’s not all that unreasonable. So, python rescues us again:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

def tryKey(key):

basicBlock = []

rollingSum = 0

keyLen = 0xC

for i in range(0x100):

basicBlock.append(i)

for j in range(0x100):

rollingSum = (rollingSum + (ord(key[j%keyLen]) + basicBlock[j])) & 0xFF

basicBlock[j], basicBlock[rollingSum] = basicBlock[rollingSum], basicBlock[j]

return basicBlock

def crypt(whichBlock, a, b):

inputFile = bytearray((open(sys.argv[1], 'rb').read()))

swapped256 = bytearray(whichBlock)

counter0 = 0

counter1 = 0

encryptedFile = inputFile

swapValList = []

for index in range(len(inputFile)):

counter0 = (counter0 + 1) & 0xFF

counter1 = (counter1 + swapped256[counter0]) & 0xFF

swapped256[counter0], swapped256[counter1] = swapped256[counter1], swapped256[counter0]

sumOfSwappyVals = (swapped256[counter0] + swapped256[counter1]) & 0xFF

swapValList.append(sumOfSwappyVals)

encryptedFile[index] = inputFile[index] ^ swapped256[sumOfSwappyVals]

open('crypt-a-' + str(a) + '-b-' + str(b), 'wb').write(str(encryptedFile))

return 0

print "==============Crypt=============="

alphaBits = ['0','1','2','3','4','5','6','7','8','9','a','b','c','d','e','f']

for a in alphaBits:

for b in alphaBits:

key = ['0','0','1','c','4','2','9','2','d','f', a, b]

crypt(tryKey(key), a, b)

$ ./finCrypt4.py PANW_Top_Secret_Sauce.jpg.encrypted

==============Crypt==============

$ file * | grep JPEG

crypt-a-d-b-7: JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01, resolution (DPI), density 72x72, segment length 16, Exif Standard: [TIFF image data, big-endian, direntries=5, orientation=upper-left, xresolution=74, yresolution=82, resolutionunit=2], progressive, precision 8, 600x752, frames 3

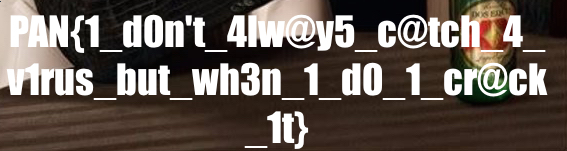

so the mystery byte was d7, and the mystery flag is:

PAN{1_d0n’t_4lw@y5_c@tch_4_v1rus_but_wh3n_1_d0_1_cr@ck_1t}