Level 5: revfest

Description:

You walk to the south...

A goblin makes a telltale startup sound and hands you your last challenge for this

area.

7z Download

7z Password: labyrenth

Hint: 3.805.184 bytes, 9783 identified and many unidentified functions, 5 levels of

pure fun with MFC.

Author(s): @xedi25

http://dl.labyrenth.com/multistage/15b7a0a936a9a53324b40c16e936ac6b4f4374ecdde3a2267f0434e4ca18ef7c.7z

Alternate binary download link

Step 0: Hints

A quick google search for reversing MFC applications/binaries turns up a few interesting resources, but…let’s just see how far we get before we really need to dig into some extra help.

Step 1: Initial triage and recon

$ file revfest.exe

revfest.exe: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows

It turns out the binary track was essentially just the Windows track with a bonus.

The strings output is a little overwhelming, but some stubborn quick scrolling reveals a few things:

Level1

vector<T> too long

invalid string position

string too long

Level2

d2fea7286d3754f84eb55da4d030d72a4de9ee079a526087619227c2b62aa86f

Level3

%s\notepad.exe

Level4

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTU

VWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/PANDAPANDAPANDAPANDAPANDAPabcdefghijklmnop

qrstuvwxyz0123456789+/PANDEFGHIJKLMCOBQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+

/abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789+/QpaZIivj4ndG=H021y+N

O5RSa/xPgUz67FMhYq8b3wemKfkJLBocCDrs9VtWXlEu1OnZyI5vyCFn+Yf=NOV2Oii+ODy55qUTR5wncUj5r

UsFVzhQB=h=CHNTs0ZYmGLAAabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789+/abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789+/QpaZIivj4ndGH021y+NO5RST/xPgUz67FMhYq8b3wemKfkJLBocCDrs9VtWXlEuA

Level5

Selected $strings -e l output:

HideDebugger.dll

mY0dKWWn0[EN\XZhdE:0N\W0ZQSE{gYN\0LQJ0QY0WZaSXKa~W0JNKORNOKW0VWJ]Tigf0QYV0SO]Z~0SE0N\W0jgdgifa{u0QKN]U]RWK0fQWVQZOJ0UXK0n]id0k]ihz0XU0bKgNg0QN0nYXzzhJ9

Wrong counter: %u

SeDebugPrivilege

FATAL ERR0R. NEED MORE INTERNET.

Start level %u!

Done.

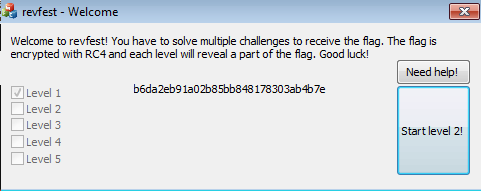

revfest - Welcome

MS Shell Dlg

Let's start!

Welcome to revfest! You have to solve multiple challenges to receive the flag. The flag is encrypted with RC4 and each level will reveal a part of the flag. Good luck!

Level 1

Level 2

Level 3

Level 4

Level 5

Need help!

040904b0

Level 1

MS Shell Dlg

Cancel

Please enter the correct password:

Level 2

MS Shell Dlg

Cancel

Please enter the correct password:

Level 3

MS Shell Dlg

Cancel

Please enter the correct password:

Level 4

MS Shell Dlg

Cancel

Please enter the correct password:

Level 5

MS Shell Dlg

It might not be a really good idea to go on a renaming/string xref spree because there are simply too many rabbit holes. Perhaps we should use some dynamic analysis to guide our renaming/xref spree.

The presence of a “HideDebugger.dll” string is particularly interesting, as that is the dll that the IDA Stealth plugin uses. Good thing we are using scylla hide instead.

I have not mentioned it so far, but it is especially important this time since we know so little about this binary, but you should make sure that you are ready to run malware in your VM.

You can read more about setting up such an environment in Chapter 2 of Practical Malware Analysis.

Alternatively, you can say…whatever, this probably isn’t real malware. Indeed, this whole series of walkthroughs has been functioning on that assumption and approaching the binaries as CTF challenges more than malware.

Step 2: Dynamic Analysis

Anyway, let’s run this thing and see what happens. I’ll continue with the assumption that it is more CTF than malware and skip all the monitoring for now (fakenet, regshot, procmon, procexp, etc.).

Level 1

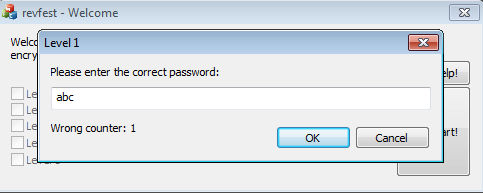

So let’s burrow our way into this binary’s logic through the wrong counter. It increases every time we submit a wrong password, so we should be able to work our way backwards from it to find the password validating logic.

We open up the binary in IDA, then attach to the process using Debugger -> Attach to process

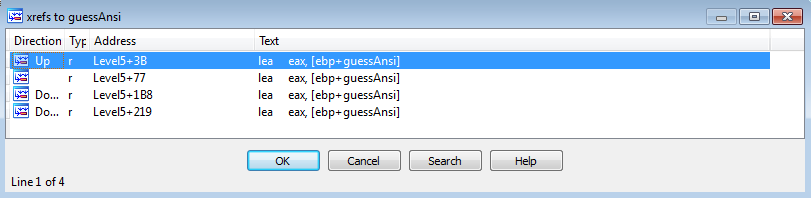

In the strings window, we ctrl+f and search for wrong. Examining the xrefs for this string:

5 levels, 5 xrefs. Ok.

We click on the address of the Wrong counter string, then set a breakpoint on all data xrefs to it:

for ref in DataRefsTo(ScreenEA()):

AddBpt(ref)

We go ahead and submit our wrong password again, and see which breakpoint triggers.

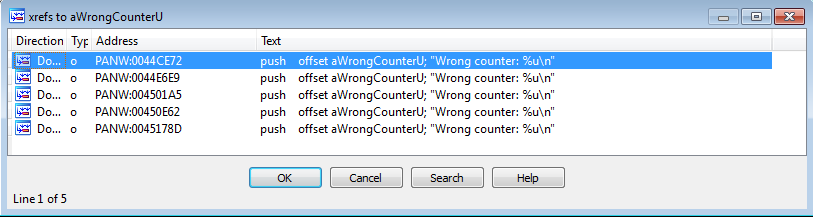

IDA has not recognized this as a function, so we don’t have the nice Control Flow Graph (CFG). That’s an easy fix here, we just scroll up until we see a function prologue:

PANW:0044CBE6 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

PANW:0044CBE9 align 10h

PANW:0044CBF0 push ebp

PANW:0044CBF1 mov ebp, esp

PANW:0044CBF3 push 0FFFFFFFFh

PANW:0044CBF5 push offset sub_5CD8D0

PANW:0044CBFA mov eax, large fs:0

PANW:0044CC00 push eax

PANW:0044CC01 mov large fs:0, esp

PANW:0044CC08 sub esp, 3F0h

PANW:0044CC0E push ebx

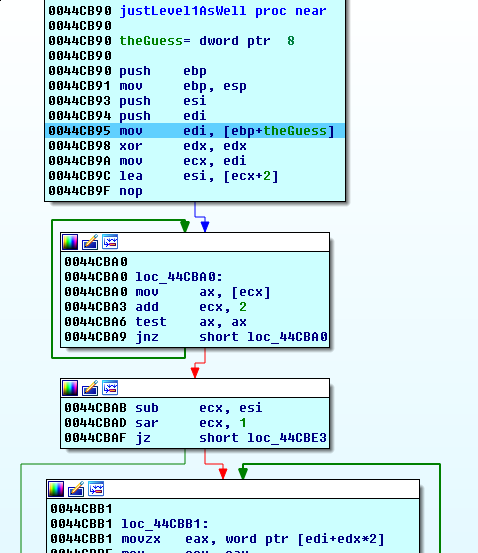

then click on the push ebp and press p. We rename this function to Level1 and press space bar for our nice CFG. We take a moment to rename the other breakpoints Level B, C, D, and E so we can spot them easily in cross references.

We scroll around note the many failing edges which lead to the wrong counter block. There are also many calls to other functions. Too many, if you ask me.

Well, we click on them and examine the xrefs. It seems that they are being used repeatedly, and within various functions.

The naming convention quickly breaks down under so much data/code. We can resort to naming the functions by how much they’re being called. We will spend less time on a libManyCall, than a lib3Call. We will focus our reversing efforts on such excellently named functions as justLevel1, justLevel1AsWell.

With this new naming convention covering our Level1 function, we set a breakpoint at the top of the Level1 function so we can examine dynamically what leads to the Wrong counter block, and how our input is used.

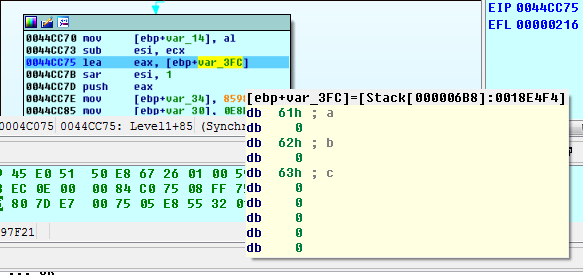

We submit our wrong guess, step through examining the buffers/arguments and register assignments until we spot our input. Along the way, we fix some offsets by undefining them u and converting to unicode alt-a where applicable.

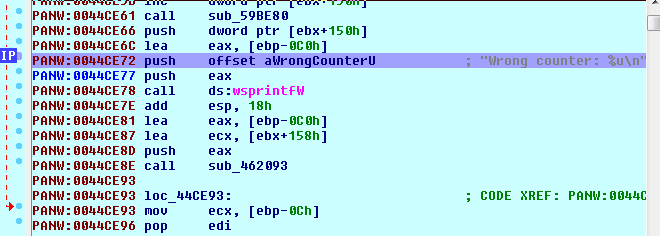

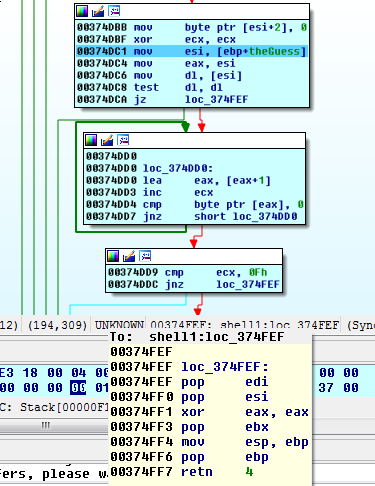

We note this loop that gets the string length of whatever was in esi, via pointer arithmetic:

PANW:0044CC70 mov [ebp+var_14], al

PANW:0044CC73 sub esi, ecx

Keep this idiom in mind, so it’ll be easy to spot later.

We take a couple more steps and find our input:

Ignoring the stack string thing, we examine this basic block:

PANW:0044CC70 mov [ebp+var_14], al

PANW:0044CC73 sub esi, ecx

PANW:0044CC75 lea eax, [ebp+theGuess]

PANW:0044CC7B sar esi, 1

PANW:0044CC7D push eax

PANW:0044CC7E mov [ebp+var_34], 8598E95h

PANW:0044CC85 mov [ebp+var_30], 0E8E52039h

PANW:0044CC8C mov [ebp+var_2C], 6DF732B1h

PANW:0044CC93 mov [ebp+var_28], 0A33675EEh

PANW:0044CC9A mov [ebp+var_24], 0DE0AE9F6h

PANW:0044CCA1 mov [ebp+var_20], 3E0178A4h

PANW:0044CCA8 mov [ebp+var_1C], 14F8BA2Eh

PANW:0044CCAF mov [ebp+var_18], 95089C61h

PANW:0044CCB6 call justLevel1AsWell

PANW:0044CCBB cmp ebx, esi

PANW:0044CCBD jnz wrongCounter

esi, which held the distance between the start of the “mY0dKWWn0[EN" blah blah string, and the end of it, is divided by 2 (sar esi, 1) to get the character count (rather than the length including the 00 bytes of each wide character).

It is then compared to ebx, which holds a 3 for us at the moment. That is likely the length of our input (theGuess).

Well, so now we know that our input has to be 0x97 characters long. This is good news, since…we must be able to calculate it as a brute force would be unreasonable.

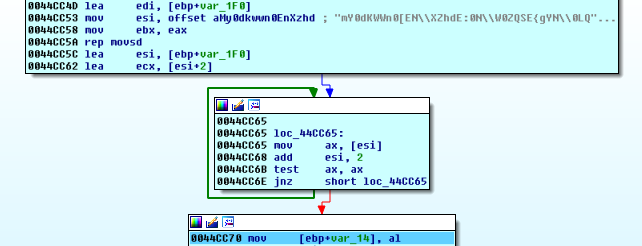

Examining where ebx was assigned leads us to this code in the first basic block of Level1:

PANW:0044CC41 mov ecx, eax

PANW:0044CC43 call libManyCall2

PANW:0044CC48 mov ecx, 4Ch

PANW:0044CC4D lea edi, [ebp+var_1F0]

PANW:0044CC53 mov esi, offset aMy0dkwwn0EnXzhd ; "mY0dKWWn0[EN\\XZhdE:0N\\W0ZQSE{gYN\\0LQ"...

PANW:0044CC58 mov ebx, eax

PANW:0044CC5A rep movsd

PANW:0044CC5C lea esi, [ebp+var_1F0]

PANW:0044CC62 lea ecx, [esi+2]

libManyCall2 has now become very interesting, we step inside of it and see if this is our input length calculator.

Of all the things this function might do, we are most interested in this one block:

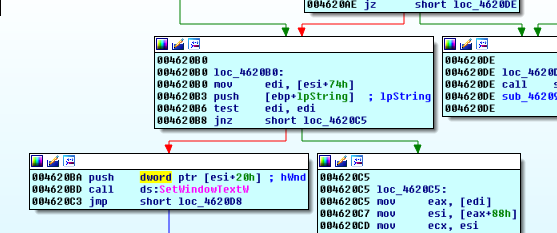

We set a breakpoint on GetWindowText, and go read a little bit of MSDN.

Copies the text of the specified window’s title bar (if it has one) into a buffer. If the specified window is a control, the text of the control is copied.

Return value

Type: int If the function succeeds, the return value is the length, in characters, of the copied string, not including the terminating null character.

Cool.

Since this is used in all of the levels, we just learned something very useful…where our input from the textbox comes in.

We rename this function to getWindowText. We run to the line that calls getWindowText and examine the stack.

Our input will be stored at 0x18E4F4. Clicking in the hex dump under the disassembly window, we press g and enter this address.

This time, we step into justLevel1AsWell

PANW:0044CCB6 call justLevel1AsWell

PANW:0044CCBB cmp ebx, esi

PANW:0044CCBD jnz wrongCounter

It takes 1 argument, our input.

Already, we can recognize what a significant portion of this function does. It is another string length loop.

We reverse the algorithm here and translate it to python:

>>> guess = [0x61,0x62,0x63]

>>> newGuess = []

>>> for c in guess:

... newGuess.append(c^(c/2))

...

>>> ''.join(map(chr, newGuess))

'QSR'

0018E4F4 51 00 53 00 52 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 Q.S.R

We go ahead and force the jump by setting the zero flag manually, or editing ebx so that it is 0x97 (click on ebx in the registers window and press e).

We see that our transformed input is being compared to the mY0blahblah buffer at matching indexes. We can find matching values with a little bit of python:

Python>list(GetManyBytes(0x18E700, 0x97*2))

#!/usr/bin/env python

theBytesW = ['m', '\x00', 'Y', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'd', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', 'n', '\x00', '0', '\x00', '[', '\x00', 'E', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', '\\', '\x00', 'X', '\x00', 'Z', '\x00', 'h', '\x00', 'd', '\x00', 'E', '\x00', ':', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', '\\', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'Z', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'S', '\x00', 'E', '\x00', '{', '\x00', 'g', '\x00', 'Y', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', '\\', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'L', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'J', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'Y', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', 'Z', '\x00', 'a', '\x00', 'S', '\x00', 'X', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', 'a', '\x00', '~', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'J', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', 'O', '\x00', 'R', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', 'O', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'V', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', 'J', '\x00', ']', '\x00', 'T', '\x00', 'i', '\x00', 'g', '\x00', 'f', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'Y', '\x00', 'V', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'S', '\x00', 'O', '\x00', ']', '\x00', 'Z', '\x00', '~', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'S', '\x00', 'E', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', '\\', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'j', '\x00', 'g', '\x00', 'd', '\x00', 'g', '\x00', 'i', '\x00', 'f', '\x00', 'a', '\x00', '{', '\x00', 'u', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', ']', '\x00', 'U', '\x00', ']', '\x00', 'R', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'f', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'W', '\x00', 'V', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'Z', '\x00', 'O', '\x00', 'J', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'U', '\x00', 'X', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'n', '\x00', ']', '\x00', 'i', '\x00', 'd', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'k', '\x00', ']', '\x00', 'i', '\x00', 'h', '\x00', 'z', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'X', '\x00', 'U', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'b', '\x00', 'K', '\x00', 'g', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', 'g', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'Q', '\x00', 'N', '\x00', '0', '\x00', 'n', '\x00', 'Y', '\x00', 'X', '\x00', 'z', '\x00', 'z', '\x00', 'h', '\x00', 'J', '\x00', '9', '\x00']

winString = []

for byte in theBytesW:

for x in xrange(0x20,0x7F):

if x^(x/2) == ord(byte):

winString.append(x)

print ''.join(map(chr,winString))

and we get:

$ ./theBytesW.py

In GreeK mytholOGy, the labyREnth was an elAborATe structure desigNED and builT by the LEGENDARY artificer Daedalus for KiNG MiNOS of CrEtE at KnoSSOs.

We press F9 to fail, but we now have the right input for the next run. We paste our guess into the box and hope to hit the Wrong counter for Level 2.

It may be worth our while to find out where the b6da string came from, in case we need to do something with this string, or at least transcribe it.

Oh well for now, let’s catch it on the next one.

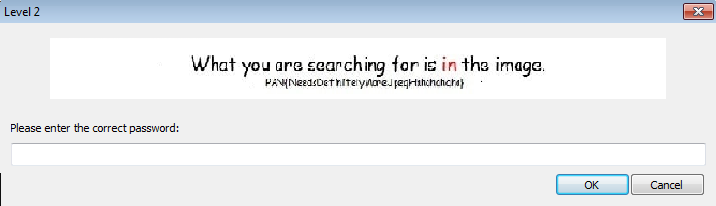

Level 2

It’s tempting to guess what’s written in the image. This is certainly a doomed approach, but we might learn something along the way, so we submit a guess anyway. At least we will find the Level 2 code.

PAN{NeedsDefinitelyMoreJpegHimomchchra} ?

We submit the guess and find ourselves at the GetWindowText breakpoint. We return from here and rename this function Level2.

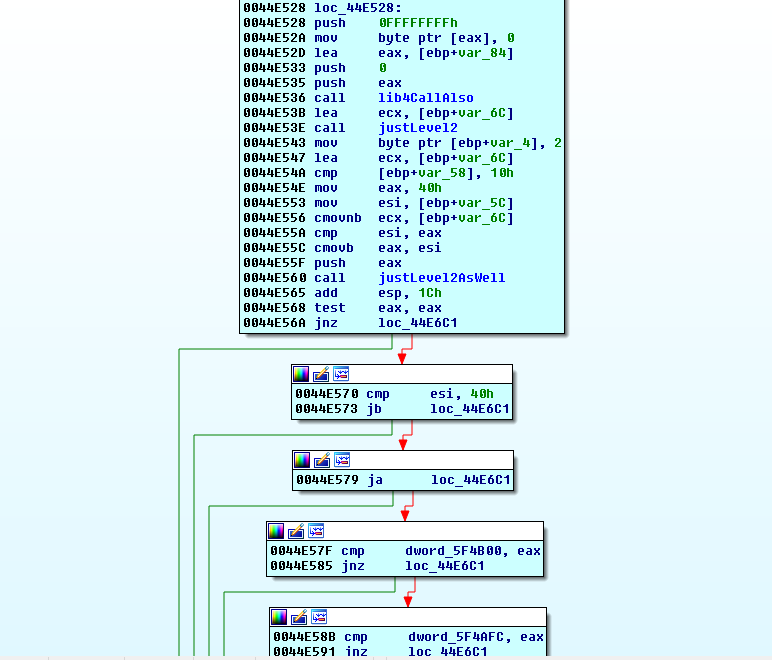

There are a lot of similarites between Level1 and Level2, we take advantage of that and focus on the parts unique to Level2. Playing the same count the xrefs game, we try to find the unique Level2 code.

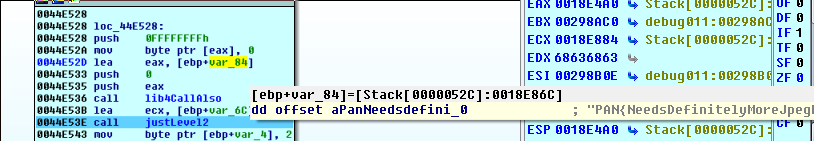

This turns out to be a pretty good game, and we have quickly found the code unique to Level2:

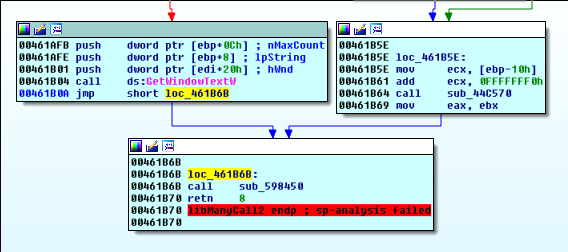

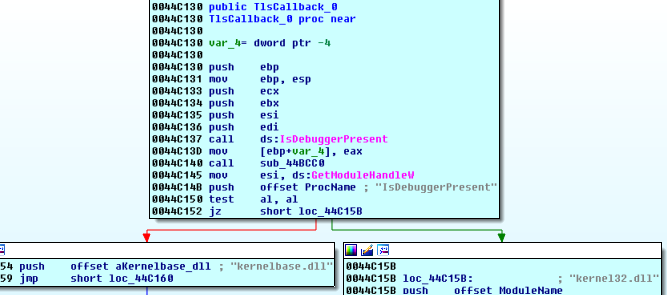

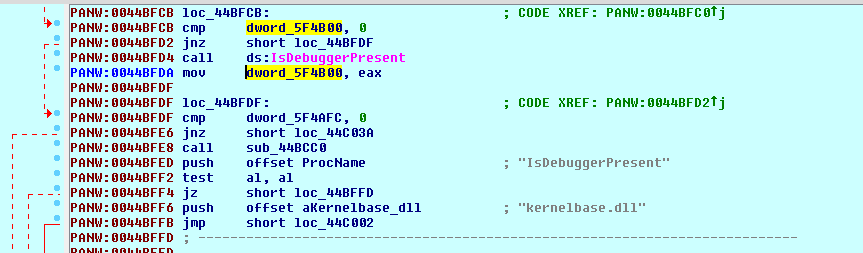

The cascading checks that lead to the wrong counter block are present again. The dwords actually resolve to a series of anti-debug checks, but Scylla Hide has really helped us out here. This binary would have been more trouble otherwise. We could have also found these features by following the hint about the HideDebugger.dll string. It would lead us to the TLS callback that IDA identified:

Google “TLS Callback malware” for some extra reading material on this subject. Alternatively (and to no one’s surprise at this point), you can find more information about this in Chapter 16 of Practical Malware Analysis. It’s a seriously excellent book, and worth every second and dollar you’d spend on it. I was lucky enough to have access to it through Books24x7 when I was in school, but I definitely also bought a copy when the nostarch humble bundle came out. I owe almost every bit of my reversing methodology and knowledge to this book.

Anyway, perhaps we will put on our malware analysis hats and explore the anti-debug features of this binary after we win. For now…let’s get flags.

We label our guess buffer, and click on the first function unique to Level 2:

PANW:0044E53B lea ecx, [ebp+var_6C]

PANW:0044E53E call justLevel2

We press F4 to run to this point. We look at the surrounding buffers for our guess, and we find it:

We rename the buffer, and take a look inside justLevel2.

None of this looks like fun, and the bunch of math suggests that the crypto monster has made another appearance.

Let’s see if FindCrypt can spot anything interesting:

The only thing found that was not in library addresses were some SHA256 constants.

43CDA0: found const array SHA256_K (used in SHA256)

PANW:0043CDA0 SHA256_K dd 428A2F98h ; DATA XREF: sub_452180+120r

PANW:0043CDA4 dd 71374491h, 0B5C0FBCFh, 0E9B5DBA5h, 3956C25Bh, 59F111F1h, 923F82A4h

Following the xrefs back:

the SHA256_K const array is connected to the sub_452180, the sub_452180 is connected to…a couple of things, one of those things is sub_452380 which is connected to justLevel2+C6

Nice…

PANW:004526B6 call sub_452380

PANW:004526BB lea eax, [ebp+var_34]

So, let’s step over the justLevel2 function, and examine the buffers that come out of it…

Maybe one of them is sha256(PAN{NeedsDefinitelyMoreJpegHimomchchra})?

$ echo -n "PAN{NeedsDefinitelyMoreJpegHimomchchra}" | sha256sum

7ccee2400897ff366ef0e3f57789f644fffe2bce5313a4d110d4871616d22d28

Note the use of -n to prevent echo from adding the newline that’ll have you questioning your sanity when comparing hashes.

The buffer that was sent in to the crazy mess, has returned with a…unk_298B18?

Double click the unk, and:

debug011:00298B18 unk_298B18 db 37h ; 7

debug011:00298B19 db 63h ; c

debug011:00298B1A db 63h ; c

debug011:00298B1B db 65h ; e

debug011:00298B1C db 65h ; e

debug011:00298B1D db 32h ; 2

debug011:00298B1E db 34h ; 4

debug011:00298B1F db 30h ; 0

debug011:00298B20 db 30h ; 0

debug011:00298B21 db 38h ; 8

debug011:00298B22 db 39h ; 9

or, if we apply a to the first byte:

debug011:00298B18 a7ccee2400897ff36 db '7ccee2400897ff366ef0e3f57789f644fffe2bce5313a4d110d4871616d22d28',0

and many headaches were avoided this day.

With an unwarranted confidence, we do a few F8 steps until we reach the next function of interest:

PANW:0044E53E call justLevel2

PANW:0044E543 mov byte ptr [ebp+var_4], 2

PANW:0044E547 lea ecx, [ebp+sha256ofGuess]

PANW:0044E54A cmp [ebp+var_58], 10h

PANW:0044E54E mov eax, 40h

PANW:0044E553 mov esi, [ebp+var_5C]

PANW:0044E556 cmovnb ecx, [ebp+sha256ofGuess]

PANW:0044E55A cmp esi, eax

PANW:0044E55C cmovb eax, esi

PANW:0044E55F push eax

PANW:0044E560 call justLevel2AsWell

PANW:0044E565 add esp, 1Ch

PANW:0044E568 test eax, eax

PANW:0044E56A jnz wrongCounter

The code after this is the cascading anti-debug checks. So the decision inside of justLevel2AsWell is essentially the input validation logic.

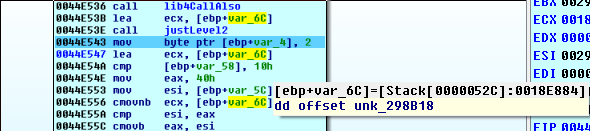

A quick look inside justLevel2AsWell tells the story rather quickly:

We see a familiar loop pattern that compares 4 bytes at a time, we see a hardcoded string that looks like a sha256 sum, and it will be compared against our sha256 sum.

It looks like the flag validation routine for Level 2 is essentially a question…does sha256(yourGuess) equal this sha256 sum?

There is no brute force to be had here. There is no calculation either.

We must be given the answer. So we take the hint quite literally, that the answer is in the image.

Originally, when solving this challenge, I went down some rabbit holes of watching this binary load the resource image, and examine what calculations were being done. Perhaps there was a clue there. I’ll spare you the details of that rabbit hole, and we will go on with the good ideas.

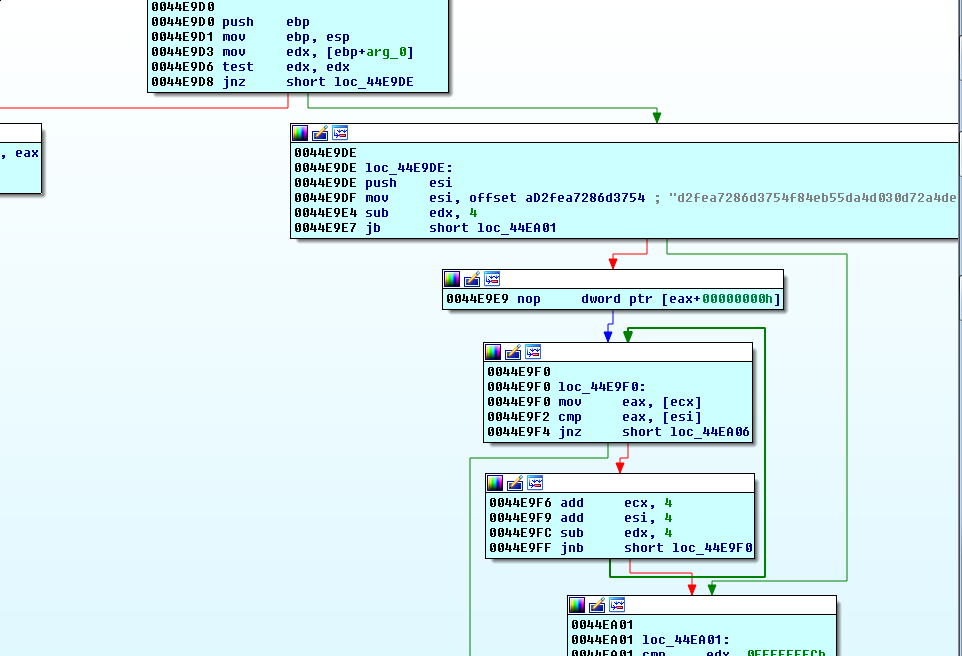

Let’s take the image out of this binary, and peform some sort of forensics or surgery.

There are many tools we can use to extract the resources from this binary, but I prefer Resource Hacker. (Guess where I learned this trick?)

We open the binary in RH and expand the PNG folder. There are two at the very bottom whose names stand out. Clicking on them we find our image, and save it as a png.

I have just a few tricks when it comes to steganalysis/forensics.

- Strings

- Hex-editor to apply a xor of the most common byte

- Fix broken headers

- Run Stegsolve on the image

- Run zsteg on the image

- Carve files with binwalk/foremost

- Adjust some colors with an image editor

- Try a random thing that makes no sense and never works

It just so happens that #5 is the winner today.

# gem install zsteg

# zsteg savedGarbled.png

b1,rgb,lsb,xy .. text: "55:Did you think that I have used JPEG to store this flag?"

b1,bgr,lsb,xy .. file: PGP\011Secret Key -

b2,b,msb,xy .. text: "_]W}W]W]WUW]_"

b3,abgr,msb,xy .. file: MPEG ADTS, layer I, v2, 256 kbps, Monaural

b4,b,msb,xy .. file: MPEG ADTS, layer I, v2, 112 kbps, 24 kHz, JntStereo

My apologies for the anti-climactic end to Level 2. On the bright side, we can all just forget about Level 2 now.

Let’s at least track where the key for Level 2 will be written to the window after submitting the correct flag.

It seems likely that it would be the same function responsible for printing the Wrong counter to the window.

PANW:0044E6E9 push offset aWrongCounterU ; "Wrong counter: %u\n"

PANW:0044E6EE push eax ; LPWSTR

PANW:0044E6EF call ds:wsprintfW

PANW:0044E6F5 add esp, 18h

PANW:0044E6F8 lea eax, [ebp+String]

PANW:0044E6FE lea ecx, [ebx+150h]

PANW:0044E704 push eax ; lpString

PANW:0044E705 call sub_462093

We take a look inside sub_462093 and find the following:

We set a breakpoint:

004620B3 push [ebp+lpString] ; lpString

and now we can see what will be printed to the window.

We submit the proper Level 2 input “Did you think…”, and we hit the lpString breakpoint:

debug011:00298AC0 unicode 0, <174954d21100331514edef46c5219daa>,0

Level 3

We carry out the submit a guess, rename the function we return to after the window text is retrieved, rename the surrounding buffers strategy as we find ourselves in the Level 3 code.

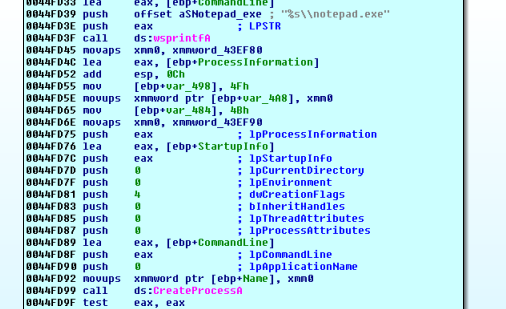

We step through, and we see a whole bunch of bytes placed on the stack. We keep going and it starts to look a lot like the beginnings of some process hollowing:

All the previous stack action is probably the code that will be executed inside of notepad.exe

We scroll down to look ahead and set breakpoints on important calls:

WriteProcessMemory, CreateRemoteThread.

It might not be a bad idea to programmatically set breakpoints on these calls. Refreshing our memory with the IDA docs:

we come up with the following:

Python>for ref in CodeRefsTo(0x5F5484, 0): AddBpt(ref)

where 0x5F5484 is the address for WriteProcessMemory in the IAT.

We repeat the process for CreateRemoteThread (0x5F5480).

Nothing stands out in regards to our input being processed, perhaps the hollow process will do something with it. Confirming that our breakpoints were set, we press F9 and examine the source and destination for the bytes being written.

PANW:0044FDE7 push ecx ; lpBuffer

PANW:0044FDE8 push eax ; lpBaseAddress

PANW:0044FDE9 push edi ; hProcess

PANW:0044FDEA call ds:WriteProcessMemory

It turns out that our guess is written into the memory of this process.

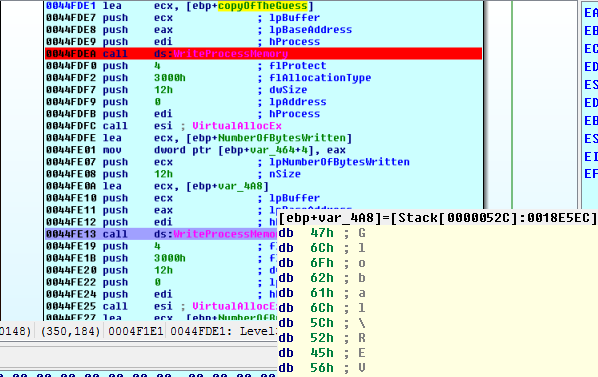

We press F9 to see what the next surprise will be:

We examine this area of memory:

Stack[0000052C]:0018E5EC aGlobalRevfest_no db 'Global\REVFEST_NO',0

Stack[0000052C]:0018E5FE db 18h

Stack[0000052C]:0018E5FF db 0

Stack[0000052C]:0018E600 aGlobalRevfest_ok db 'Global\REVFEST_OK',0

These are also copied into the process’s memory.

PANW:0044FE59 lea ecx, [ebp+var_468]

PANW:0044FE5F push ecx ; lpBuffer

PANW:0044FE60 push eax ; lpBaseAddress

PANW:0044FE61 push edi ; hProcess

PANW:0044FE62 call ds:WriteProcessMemory

it isn’t immediately obvious what var_468 is, until we apply the data carousel d and see that it is an array of pointers to the buffers that we just copied into the process:

Stack[00000240]:0018E488 dd 0C0000h

Stack[00000240]:0018E48C dd 0E0000h

Stack[00000240]:0018E490 dd 0D0000h

(Note that the addresses have changed because IDA crashed, and this is a new debugging run)

We skip over what looks like some decryption routine, and we hit the next WriteProcessMemory:

At a base address of 0x140000, var_450 will be copied. Mousing over var_450 it looks very much like a function prologue. The sequence of bytes (55 8B EC).

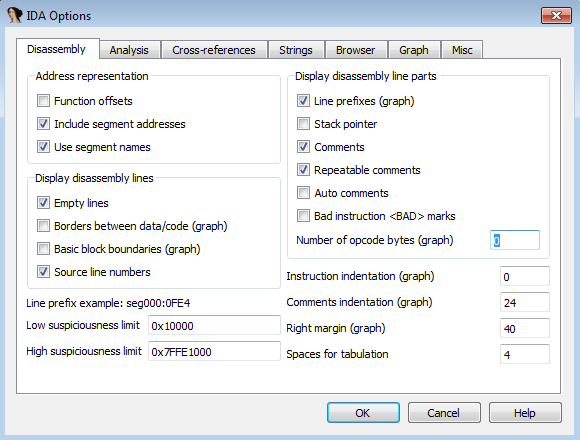

To gain this familiarity, we can have the opcodes displayed along with our disassembly by changing the Number of opcode bytes in the Options -> General window:

We let this WriteProcessMemory take place, and we press F9 to hit our next breakpoint at CreateRemoteThread.

Before we let the thread run, we want to be prepared to debug this hollowed process. As mentioned in the writeup for the first binary challenge, there are a few ways to do this.

See this blog post and comments for some ideas.

We’ll go ahead and use the break on RtlUserThreadStart method as mentioned in the first response/comment.

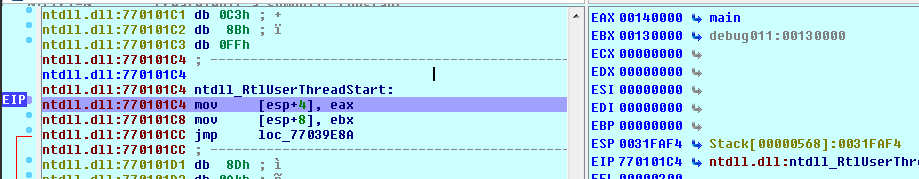

We will need another instance of IDA (or another debugger) in order to debug this other process and set this breakpoint. We’ll attach for now, and find/label our buffers and the functions that were written to the base of this process.

We go ahead and attach to the hollowed notepad.exe.

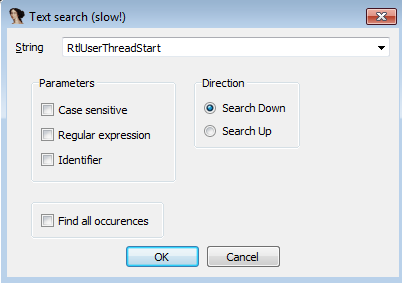

There’s likely a better way, but we can go to Search -> Text (or Alt+T) and look for RtlUserThreadStart:

We set a breakpoint, then go back to the other IDA instance to let the CreateRemoteThread call through (after setting a breakpoint on the next instruction after the CreateRemoteThread).

It works wonderfully, and we can go set a breakpoint on main before letting this function continue

We go to 0x140000

debug012:00140000 assume es:debug022, ss:debug022, ds:debug022, fs:nothing, gs:nothing

debug012:00140000 db 55h ; U

debug012:00140001 db 8Bh ; ï

debug012:00140002 db 0ECh ; 8

debug012:00140003 db 83h ; â

and press p to define this as a function. We scroll down and keep defining functions until we reach a bunch of nulls. We go back to the main function again 0x140000 and see if we can make sense of things/rename anything.

It’d be a good idea to find our input buffer, 0xC0000 and the other two buffers to see where they are used. Unfortunately, there are no xrefs to these buffers.

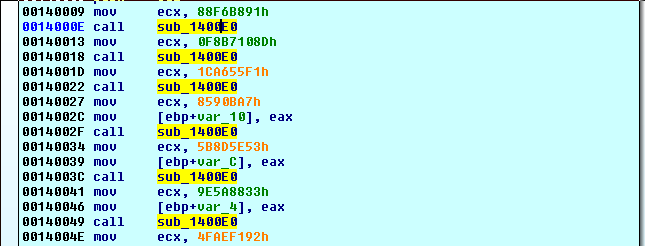

We note the repeated use of sub_1400E0:

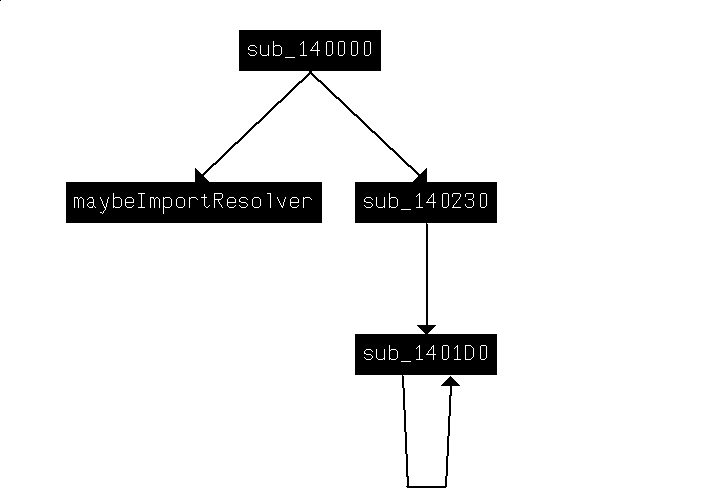

It is likely decrypting some imports. We rename it maybeImportResolver and move on.

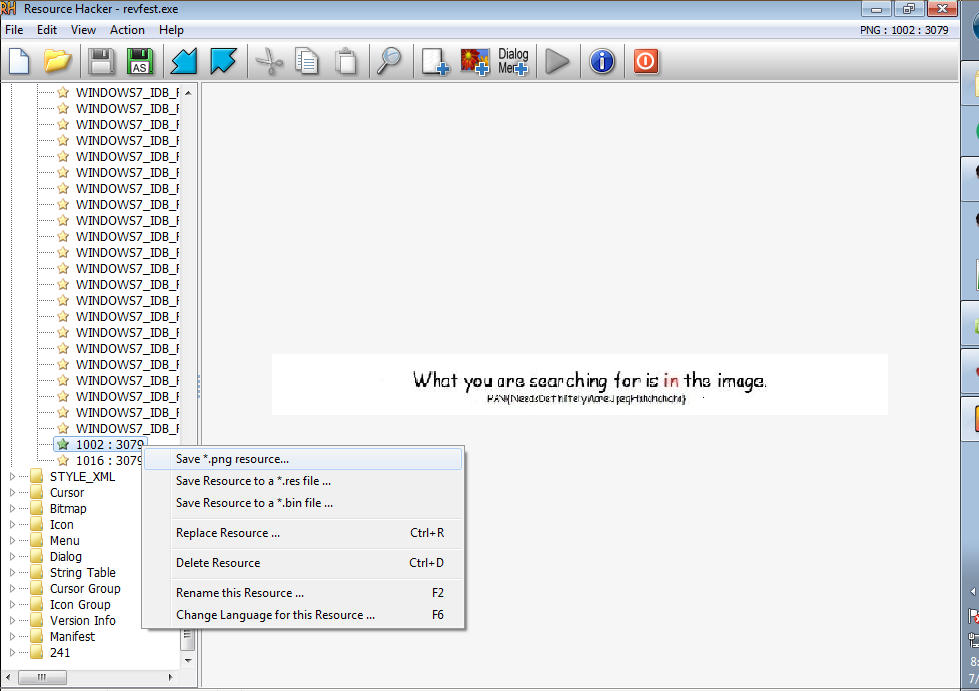

Calls to function ptrs

00140087 call edi

001400B8 call [ebp+var_4]

make this difficult to analyze statically. It makes for a deceptively nice Function call graph (Ctrl+F12) though:

We go ahead and take a quick look at these other two functions, and rename them according to their shape or any unique features.

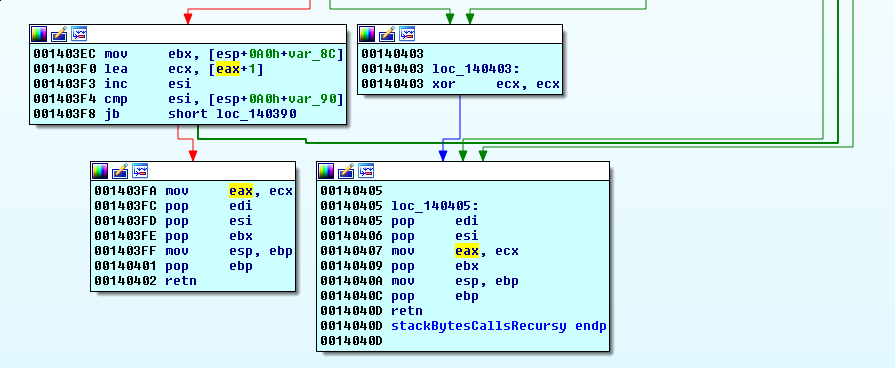

smallRecursy and stackBytesCallsRecursy? Good enough for now.

We step over the maybeImportResolver and see that it is indeed resolving imports. We rename the variable as the imports are stored in them.

Especially interesting is CreateMutexA, as we noticed a CreateMutexA in the main binary just after this hollow process received the CreateRemoteThread. We will explore this in a bit, but let’s finish getting an overview of this hollowed main.

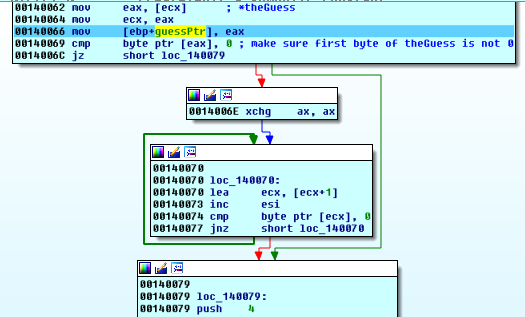

We see another length calculating loop:

and note that stosd is being used as memset, essentially:

debug012:00140090 xor eax, eax

debug012:00140092 mov edi, ebx

debug012:00140094 rep stosd

debug012:00140096 push ecx

debug012:00140097 mov ecx, [ebp+guessPtr]

debug012:0014009A mov edx, esi

debug012:0014009C push ebx

debug012:0014009D call stackBytesCallsRecursy

the rep stosd will store a double word (32 bits) from eax in edi, ecx times.

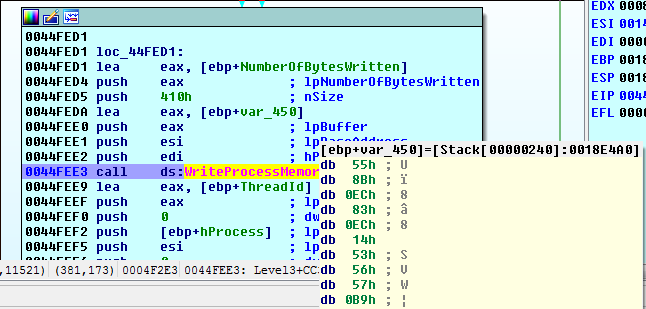

Now we turn our attention to what’s going to happen after this buffer is sent into stackBytesCallsRecursy:

If stackBytesCallsRecursy returns 0 in eax, we will push *allTheBuffers+8 onto the stack, otherwise *allTheBuffers+4.

debug011:00130000 ;org 130000h

debug011:00130000 off_130000 dd offset theGuess ; DATA XREF: Stack[00000568]:0031FA94o

debug011:00130004 dd offset aGlobalRevfes_0 ; "Global\\REVFEST_OK"

debug011:00130008 dd offset aGlobalRevfest_ ; "Global\\REVFEST_NO"

looks like we want 0x130004 and not 0x130008

The call to CreateMutexA will create a mutex with that name. Then this function will sleep for 0x7D0 milliseconds before exiting. This might make sense, depending on the CreateMutexA call in the main binary.

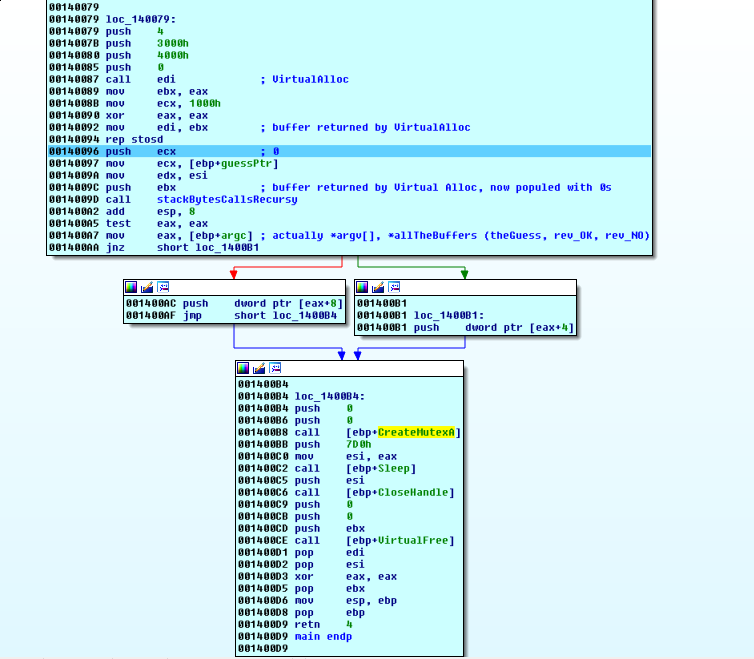

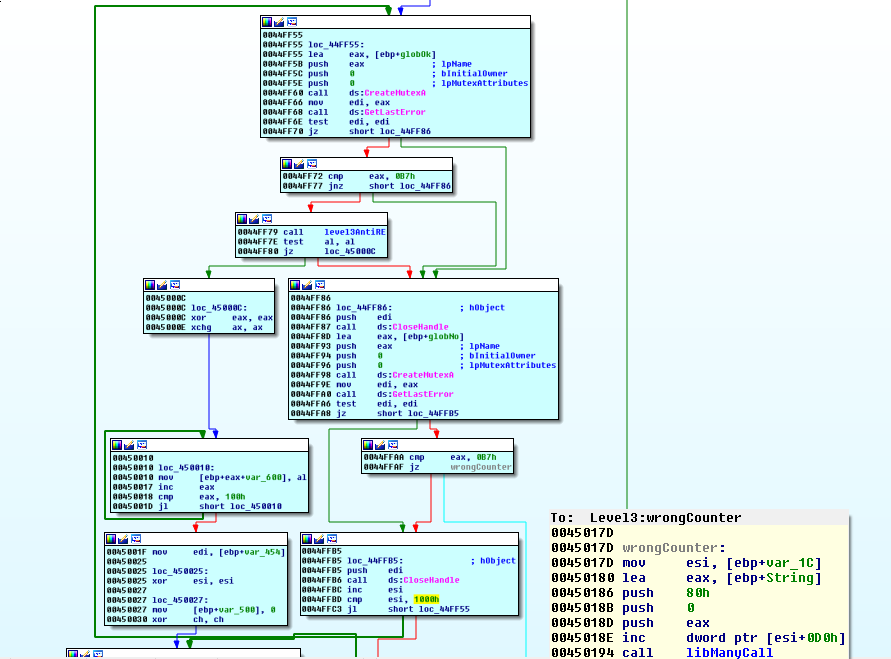

We take a quick look back at the main binary:

So, after creating the thread in the hollow process, it waits for a little while then begins a loop that attempts to create mutexes. It first attempts to create a mutex with the REVFEST_OK name. It checks the error status with GetLastError. If the error code was 0xB7 then the mutex already exists, and this function starts heading down a series of basic blocks that will miss the wrong counter block. This is likely our success state.

If this error is not returned, it attempts to create a mutex with the REVFEST_NO name. If this mutex exists (error code 0xB7), then we instantly go to the wrong counter block and fail. If this is not the error code, and this has not been attempted 0x1000 times already (esi counter xor’d before started this logic), then we loop around and try to create these mutexes again.

So, we need to find a way to return something other than 0 from stackBytesCallsRecursy so that our REVFEST_OK mutex is created. We could force it, but presumably, the flag for this level is calculated using our input.

Back to the hollowed process, we start digging in to stackBytesCallsRecursy.

debug012:0014009A mov edx, esi

debug012:0014009C push ebx ; buffer returned by Virtual Alloc, now populed with 0s

debug012:0014009D call stackBytesCallsRecursy

the esi was our calculated string length, and edx is not touched again until the bottom of sBCR’s (easier to type) first basic block:

debug012:0014037A cmp edx, 11h ; len(theGuess)

debug012:0014037D jz short loc_140388

So our input must be 0x11 bytes in length.

With no library calls left, and nothing about this algorithm seeming familiar…all that’s left is to translate this and smallRecursy into python. It may be brute forceable, we can quickly check by seeing if our input is going to be used 1 byte at a time for satisfying the constraints to leave this function using the retn on the left (returns with 1 instead of 0 in eax):

So we find our input, it was stored in ecx before this function was called:

debug012:00140230 push ebp

debug012:00140231 mov ebp, esp

debug012:00140233 and esp, 0FFFFFFF8h

debug012:00140236 sub esp, 94h

debug012:0014023C push ebx

debug012:0014023D mov ebx, ecx ; theGuess

debug012:0014023F mov [esp+98h+var_88], 1A6Dh

debug012:00140247 mov eax, 11h

debug012:0014024C mov [esp+98h+theGuess], ebx

debug012:00140250 xor ecx, ecx

so now it lives in ebx, and a local var. We follow where these are used and we see that our input is being indexed into by the loop counter, and one byte is used at a time:

We could also have set a break on read for the memory where our input is stored.

Noting the logic at the top of the series of checks:

debug012:001403DE xor eax, eax

debug012:001403E0 cmp edi, [esp+esi*8+0A0h+var_88]

debug012:001403E4 jnz short failBlock

debug012:001403E6 cmp eax, [esp+esi*8+0A0h+var_84]

debug012:001403EA jnz short failBlock

It looks like the stack vars in the first basic block of this function are the targets. We step through following the logic, then we roll down our terminals, and start pythoning.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

sys.setrecursionlimit(1000000000)

someBuff = []

theVars = [0x1A6D, 0, 0x6197ECB, 0, 0x9DE8D6D, 0, 0xBDD96882, 0, 0x148ADD, 0, 0x9DE8D6D, 0, 0xBDD96882, 0, 0x148ADD, 0, 0x29CEA5DD, 0, 0x35C7E2, 0, 0x5704E7, 0, 0x15A419A2, 0, 0x6D73E55F, 0, 0x35C7E2, 0, 0x8CCCC9, 0, 0x8CCCC9, 0, 0x9DE8D6D, 0]

theVarsEven = theVars[0::2]

theVarsOdd = theVars[1::2]

for i in range (0x4000):

someBuff.append(0)

def recursy(moddedIndex, tryBuff, someSize):

if moddedIndex == 0:

return 0

elif moddedIndex == 1:

return moddedIndex

else:

tryBuff[moddedIndex]

if tryBuff[moddedIndex] != 0:

return tryBuff[moddedIndex]

redi = recursy(moddedIndex - 2, tryBuff, 0x1000) & 0xFFFFFFFF

redi = (redi + (recursy(moddedIndex -1, tryBuff, 0x1000) & 0xFFFFFFFF) & 0xFFFFFFFF)

tryBuff[moddedIndex] = redi

return redi

def tryOne(a, tryBuff, winCount):

successFlag = 0

modIndex = (a - 0x40) & 0xFF

if modIndex == 0:

edi = 0

elif modIndex == 1:

edi = modIndex

else:

edi = tryBuff[modIndex]

if edi == 0:

edi = recursy(modIndex - 2, tryBuff, 0x1000) & 0xFFFFFFFF

edi = (edi + (recursy(modIndex -1, tryBuff, 0x1000) & 0xFFFFFFFF) & 0xFFFFFFFF)

tryBuff[modIndex] = edi

#print hex(someBuff[modIndex])

eax = 0

if edi == theVarsEven[winCount]:

if eax == theVarsOdd[winCount]:

successFlag = 1

return successFlag, tryBuff

winCount = 0

newBuff = someBuff

winBuff = []

while winCount < 0x11:

tryBuff = newBuff

win = 0

try:

for aChar in range(0x20, 0x7F):

win, newBuff = tryOne(aChar, tryBuff, winCount)

if win:

winBuff.append(aChar)

winCount += 1

except:

break

print ''.join(map(chr, winBuff))

$ ./reimp.py

This_is_labynacci

Well, it wasn’t obvious to me. When all else fails, you can definitely derp through one byte at a time.

We could edit memory, and manage some fancy breakpoint action across the two binaries. Or we can just let the wrong counter increase, and win the next round.

debug030:009890F0 aA7d61885f2fcd2eb: ; DATA XREF: Stack[00000240]:0018EF80o

debug030:009890F0 unicode 0, <a7d61885f2fcd2eb745b9f5cbcc50be5>,0

Level 4

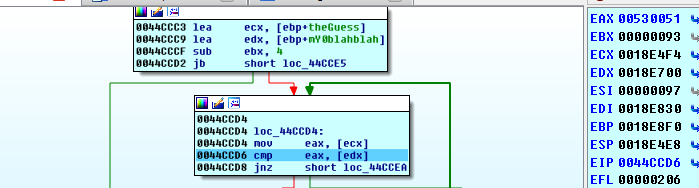

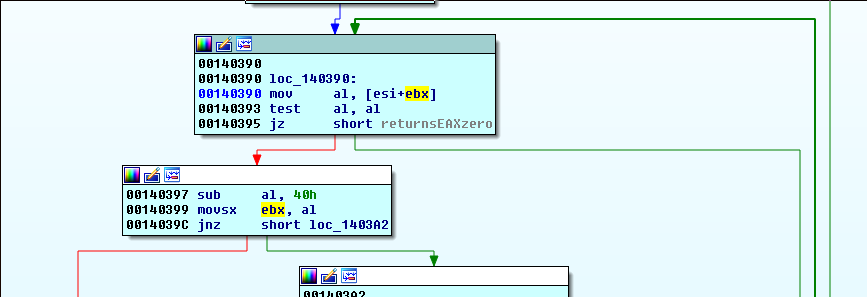

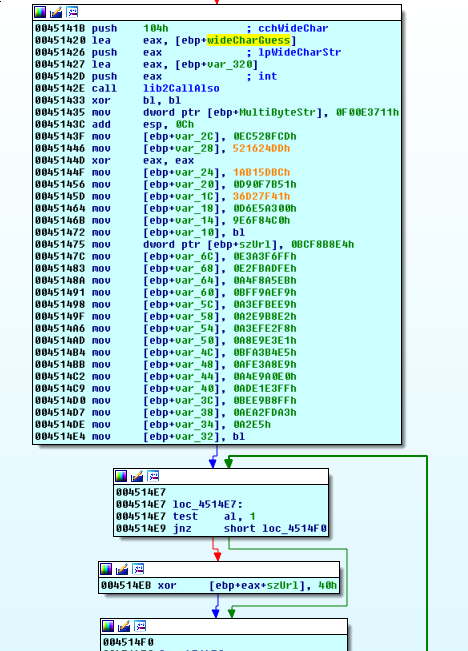

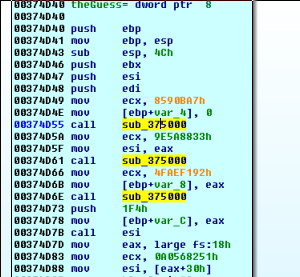

The window text is retrieved, and we take a look around Level 4. By now, we can quickly recognize the string length routines, and the anti-debug cascade.

Playing the xref game, we find the first function that is unique to Level 4 at 0x4506C4:

We go ahead and run to this point and examine the buffers going in to rename what we can.

We step inside this function, and it’s quite ugly. Scrolling around, nothing really stands out. Let’s step through, taking note of the buffers and anything else that seems interesting and see what happens.

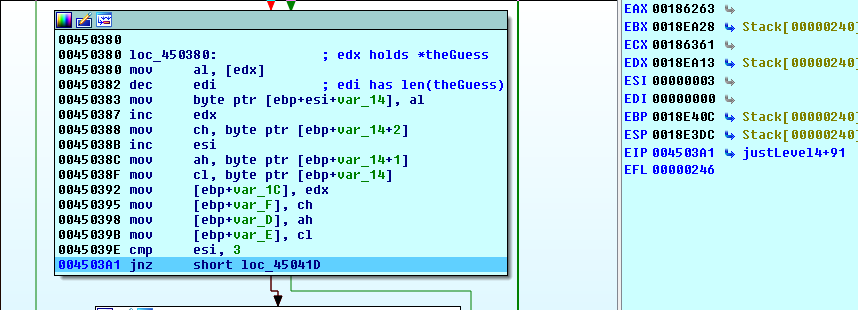

We reach a block that demands a bit of attention:

Stepping through and watching this loop, we see that it grabs 3 bytes of our input and stores them in various registers. When this loop is done, we end up with the following:

cl = guess[index]

ch = guess[index+1]

ah = guess[index+2]

some shifting/anding takes place on our bytes and then we enter another loop

It looks like there’s a bit of useless/sneaky code going around. What’s most interesting here is that this loop runs 4 times (esi was xor’d with itself just before entering this block), and it indexes some dword at an offset of esi + 0xC0 + var_18 (where var_18 is an array of the results from each byte having been shifted/anded).

PANW:004503EC movzx ecx, [ebp+esi+var_18]

PANW:004503F1 cmovnb eax, dword_5F4B8C

PANW:004503F8 movzx eax, byte ptr [ecx+eax+0C0h]

Examining dword_5F4B8C shows the following xref:

PANW:005F4B8C dword_5F4B8C dd 992888h ; DATA XREF: PANW:loc_44B110o

PANW:005F4B8C ; PANW:0044B124o ...

It looks a little strange so we undefine the 992888 by pressing u and we scroll through the data carousel d to see if it resolves to a nice pointer.

PANW:005F4B8C off_5F4B8C dd offset unk_992888

debug030:00992888 aAbcdefghijklmnopqrstu db 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/A'

debug030:00992888 ; DATA XREF: PANW:off_5F4B8Co

debug030:00992888 db 'BCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/PA'

debug030:00992888 db 'NDAPANDAPANDAPANDAPANDAPabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/PAN'

debug030:00992888 db 'DEFGHIJKLMCOBQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/abcd'

debug030:00992888 db 'efghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789+/QpaZI'

debug030:00992888 db 'ivj4ndG=H021y+NO5RSa/xPgUz67FMhYq8b3wemKfkJLBocCDrs9VtWXlEu1OnZyI'

debug030:00992888 db '5vyCFn+Yf=NOV2Oii+ODy55qUTR5wncUj5rUsFVzhQB=h=CHNTs0ZYmGLAAabcdef'

debug030:00992888 db 'ghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789+/abcdefg'

debug030:00992888 db 'hijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789+/QpaZIivj'

debug030:00992888 db '4ndGH021y+NO5RST/xPgUz67FMhYq8b3wemKfkJLBocCDrs9VtWXlEuA',0

That becomes a little more useful. We rename our dword to reflect its alphabetic nature. A few things stand out about this.

- The characters are all printable ascii

- “PANDAPANDAPANDA”

- The characters which are not alphanumeric are characters present in Base64 encoding.

We do a little bit of reading about the Base64 encoding algorithm and notice that groups of 3 characters are encoded as 4 (think back to the loop counters).

So, if this is Base64 with a custom alphabet (alphabet starting at 0xC0 in our dword), then we expect no padding to be added to our group of 3 characters (guess was ‘abc’).

Let’s grab 64 bytes starting from 0xC0 in our alphabetNmore (dword_5F4B8C), and encode our ‘abc’ guess ourselves to compare the results from this function.

Python>print GetManyBytes(0x992888+0xC0, 0x40)

PANDEFGHIJKLMCOBQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/

And modifying some borrowed python:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import base64

import string

import sys

custom = "PANDEFGHIJKLMCOBQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/"

Base64 = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/"

s = ""

encode = sys.argv[1]

result = base64.b64encode(encode);

for ch in result:

if (ch in custom):

s = s+custom[string.find(Base64,str(ch))]

elif (ch == '='):

s += "="

print result

$ ./custom64.py abc

YWJj

Let’s see if our function agrees.

Skipping ahead too eagerly, we miss where the finished buffer was stored.

Examining the buffers around the call to this function, we see the var_6C that was loaded into ecx before the call to the encoder holds some Good News!:

Stack[00000240]:0018EA28 unk_18EA28 db 59h ; Y ; DATA XREF: Stack[00000240]:0018E3E8o

Stack[00000240]:0018EA29 db 57h ; W

Stack[00000240]:0018EA2A db 4Ah ; J

Stack[00000240]:0018EA2B db 6Ah ; j

Stack[00000240]:0018EA2C db 0

or cleaned up with a:

Stack[00000240]:0018EA28 aYwjj db 'YWJj',0

and many more headaches were avoided this day. We rename var_6C to encodedGuess and F8 some more.

In the middle of the ensuing stack hash mania, we spot a sneaky cmp:

PANW:00450B58 mov [ebp+var_10C], 860222ECh

PANW:00450B62 mov [ebp+var_108], 0AF63FC4Ch

PANW:00450B6C mov [ebp+var_104], 86024BB4h

PANW:00450B76 mov [ebp+var_100], 0AF64144Ch

PANW:00450B80 mov [ebp+var_FC], 86023903h

PANW:00450B8A cmp [ebp+var_5C], 48h

PANW:00450B8E mov [ebp+var_F8], 0AF64094Ch

PANW:00450B98 mov [ebp+var_F4], 86019AFCh

PANW:00450BA2 mov [ebp+var_F0], 0AF63AC4Ch

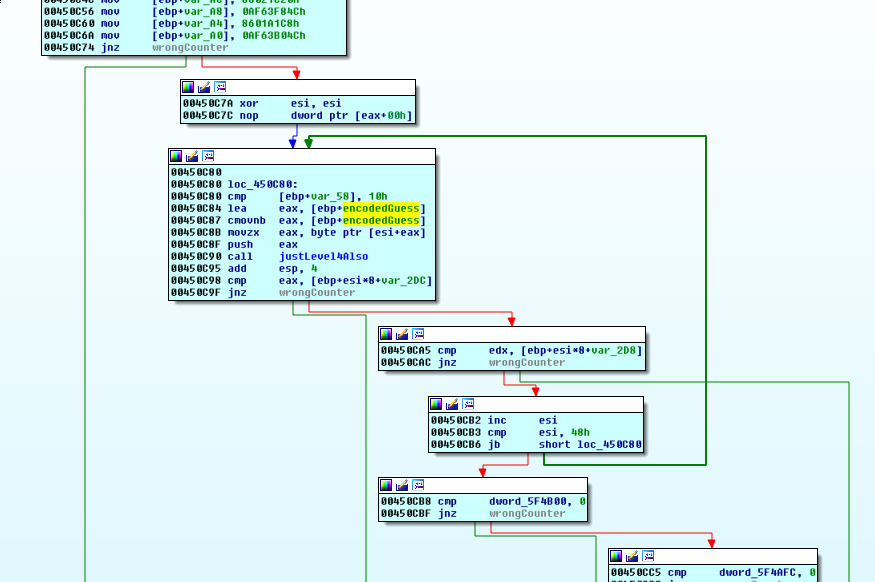

Examining the xrefs to var_5C, it seems that it is only ever written once (set to 0), and then it is read only once (during this cmp). That seems a little strange, since this cmp eventually determines whether we jump to the wrong counter, or if we continue into a loop that can send us down the anti-debug cascade to Level 5!

Well, this challenge would be impossible unless we can influence the value of var_5C. For this debug run, it holds a 4. That is not the length of our input, but it is the length of our encoded input.

Ok, so if we want a base64 encoded input that has a length of 0x48, then we need an n such that

((4 * n / 3) + 3) & ~3 = 0x48

Of course, being a brute, I say we just try:

>>> (0x48*3)/4

54

Borrowing the 64 byte string from Level 3 (not stage 3 in Level 5), and chopping off the last 10 bytes we get our new guess string:

AAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHHIIIIJJJJKKKKLLLLMMMMNN

We’ll take the wrong counter hit, and see what happens in the validation loop once we have a proper length for our input.

Round 2: AAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHHIIIIJJJJKKKKLLLLMMMMNN

We do indeed get 0x48 this time, and just a quick double check of our encoding:

debug115:009BDD48 aQufaqujnqkjdq0cdrerer db 'QUFAQUJNQkJDQ0CDREREREVFRUVGRkZGR0dHR0hISEhJSUlJSkpKSktLS0tMTExMT'

debug115:009BDD48 ; DATA XREF: Stack[00000240]:0018E884o

debug115:009BDD48 db 'U1CTU5O',0

vs

$ ./custom64.py AAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHHIIIIJJJJKKKKLLLLMMMMNN

QUFBQUJCQkJDQ0NDREREREVFRUVGRkZGR0dHR0hISEhJSUlJSkpKSktLS0tMTExMTU1NTU5O

…well. That’s a little bit of a problem. We seek a second opinion on our ability to Base64 encode/decode

Plugging in our custom alphabet: “PANDEFGHIJKLMCOBQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789”

Providing the output generated by the binary: “QUFAQUJNQkJDQ0CDREREREVFRUVGRkZGR0dHR0hISEhJSUlJSkpKSktLS0tMTExMTU1CTU5O”

and asking this site to decode it for us:

We get back our original input. That is a large relief, as we know the problem is with our python script and this really just is custom alphabet base64.

We turn to google/github and find this script. We clean it up a bit and test it:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import base64

import string

import random

cuscharset = "PANDEFGHIJKLMCOBQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/"

b64charset = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/"

encodedset = string.maketrans(b64charset, cuscharset)

decodedset = string.maketrans(cuscharset, b64charset)

def dataencode(x):

y = base64.b64encode(x)

y = y.translate(encodedset)

return y

def datadecode(x):

y = x.translate(decodedset)

y = base64.b64decode(y)

return y

plaintext = "AAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHHIIIIJJJJKKKKLLLLMMMMNN"

# Encode the plaintext string

enc = dataencode(plaintext)

# Decode back into plaintext string

dec = datadecode(enc)

print enc

print dec

$ ./custom64.py

QUFAQUJNQkJDQ0CDREREREVFRUVGRkZGR0dHR0hISEhJSUlJSkpKSktLS0tMTExMTU1CTU5O

AAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHHIIIIJJJJKKKKLLLLMMMMNN

>>> this = "QUFAQUJNQkJDQ0CDREREREVFRUVGRkZGR0dHR0hISEhJSUlJSkpKSktLS0tMTExMTU1CTU5O"

>>> that = "QUFAQUJNQkJDQ0CDREREREVFRUVGRkZGR0dHR0hISEhJSUlJSkpKSktLS0tMTExMTU1CTU5O"

>>> this == that

True

and all is well. We are ready to continue, our fears assuaged and our python skills called into question.

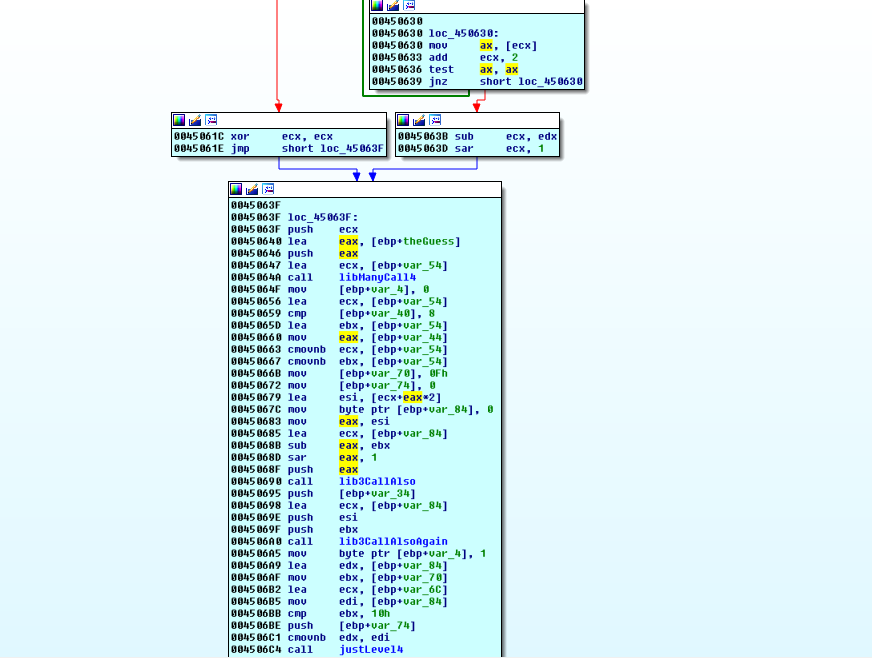

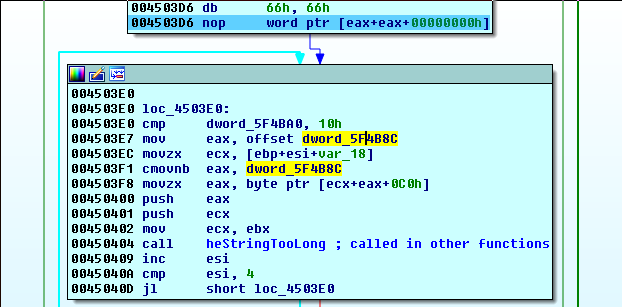

We take a few steps and receive some more good news. Our encoded input is being passed to the function inside of this loop one character at a time.

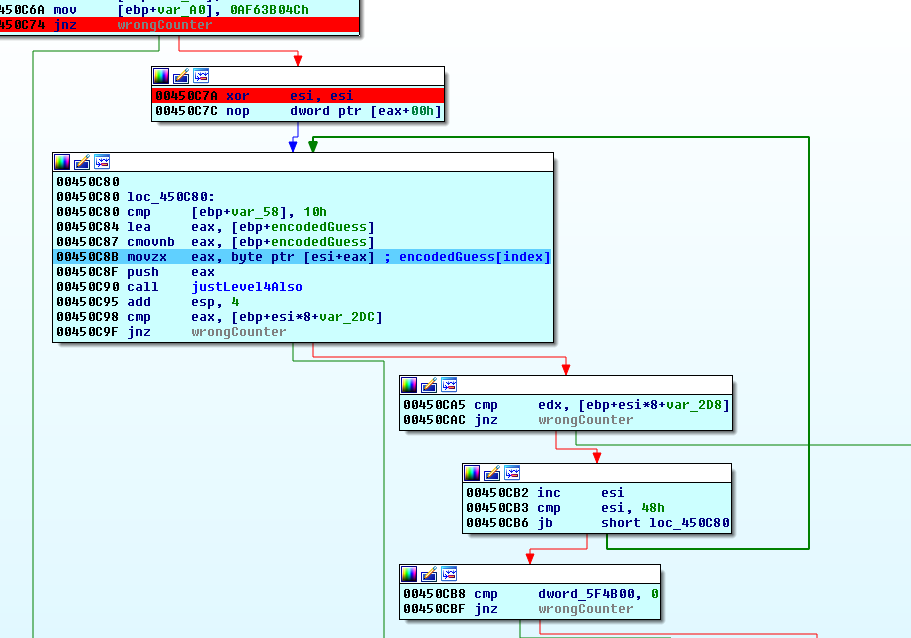

PANW:00450C80

PANW:00450C80 loc_450C80:

PANW:00450C80 cmp [ebp+var_58], 10h

PANW:00450C84 lea eax, [ebp+encodedGuess]

PANW:00450C87 cmovnb eax, [ebp+encodedGuess]

PANW:00450C8B movzx eax, byte ptr [esi+eax] ; encodedGuess[index]

PANW:00450C8F push eax

PANW:00450C90 call justLevel4Also

PANW:00450C95 add esp, 4

PANW:00450C98 cmp eax, [ebp+esi*8+var_2DC]

PANW:00450C9F jnz wrongCounter

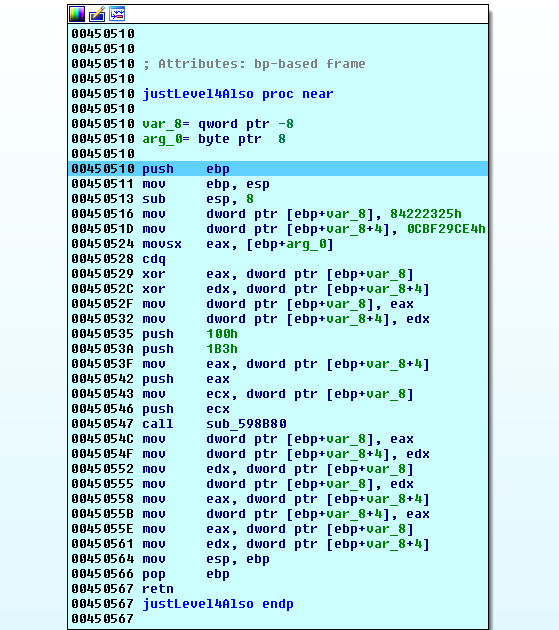

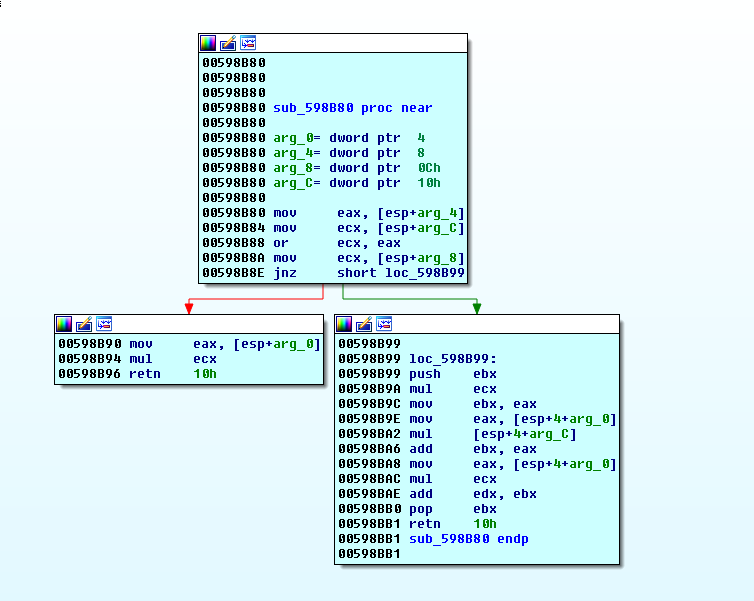

It looks like justLevel4Also might be responsible for setting the eax and edx values based on a byte from our encoded input. We step into this function to confirm:

Inside we find another function that influences the value of eax:

This doesn’t seem like a lot of code to reverse, but…at the beginning of the justLevel4Also function…there are a couple of hardcoded values that stand out:

PANW:00450510 push ebp

PANW:00450511 mov ebp, esp

PANW:00450513 sub esp, 8

PANW:00450516 mov dword ptr [ebp+var_8], 84222325h

PANW:0045051D mov dword ptr [ebp+var_8+4], 0CBF29CE4h

Findcrypt said nothing about this, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t google it ourselves.

A google search for “0x84222325 0xCBF29CE4” returns a very interesting result.

It seems that we might be dealing with a Fowler/Noll/Vo hash

It doesn’t look too painful, so we follow along. When we return to Level 4 main, we take note of this comparison:

PANW:00450C98 cmp eax, [ebp+esi*8+var_2DC]

PANW:00450C9F jnz wrongCounter

This is what all those stack bytes were for:

PANW:004506D0 mov [ebp+var_2DC], 86023750h

PANW:004506DA mov [ebp+var_2D8], 0AF64084Ch

PANW:004506E4 mov [ebp+var_2D4], 86021C20h

PANW:004506EE mov [ebp+var_2D0], 0AF63F84Ch

PANW:004506F8 mov [ebp+var_2CC], 86022139h

PANW:00450702 mov [ebp+var_2C8], 0AF63FB4C

edx will be compared to the neighbouring bytes

PANW:00450CA5 cmp edx, [ebp+esi*8+var_2D8]

PANW:00450CAC jnz wrongCounter

Ok, so we can use an implementation of this algorithm and use it in a brute force script to find the encoded bytes that will give us the right eax and edx values. Alternatively, we can just write our own weird implementation in python. I choose the latter:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import struct

crazyHashes = []

with open('crazyHashesFull', 'rb') as fp:

try:

while True:

data = struct.unpack('I', fp.read(4))[0]

crazyHashes.append(data)

except:

print "done reading"

crazyHashesEven = crazyHashes[0::2]

crazyHashesOdd = crazyHashes[1::2]

winBuff = []

iv84 = 0x84222325

ivCB = 0xCBF29CE4

hx1B3 = 0x1B3

hx100 = 0x100

index = 0

for i in range(len(crazyHashesEven)):

for aChar in range(0x20, 0x7F):

eax = ((aChar^iv84) * hx1B3) & 0xFFFFFFFF

edx = (((ivCB*hx1B3) & 0xFFFFFFFF) + (((aChar^iv84) * 0x100) & 0xFFFFFFFF) & 0xFFFFFFFF)

edx += ((aChar^iv84)*hx1B3 & 0xFFFFFFFF00000000) >> 32

if eax == crazyHashesEven[index] and edx == crazyHashesOdd[index]:

winBuff.append(aChar)

index += 1

print ''.join(map(chr, winBuff))

where crazyHashesFull is the 0x48*0x8 byte hashes starting from:

Stack[00000240]:0018E614 dd 86023750h

Python>f = open('crazyHashesFull', 'wb').write(GetManyBytes(0x18E614, 0x48*8))

Running our brute:

$ ./hashBrute.py

done reading

UEFOREEgUEFOREEgUEFOREEhIEJAU0U2CNAQQU5EQSAGTlY2CNAQQU5EQSAYT1IgUEFOREE=

then decoding:

$ ./custom64.py

UEFOREEgUEFOREEgUEFOREEhIEJAU0U2CNAQQU5EQSAGTlY2CNAQQU5EQSAYT1IgUEFOREE=

PANDA PANDA PANDA! BASE64 PANDA FNV64 PANDA XOR PANDA

debug030:009890F0 unicode 0, <15adb1715b83df39f40eb0f8f57ad75a>,0

So begins Level 5.

Level 5

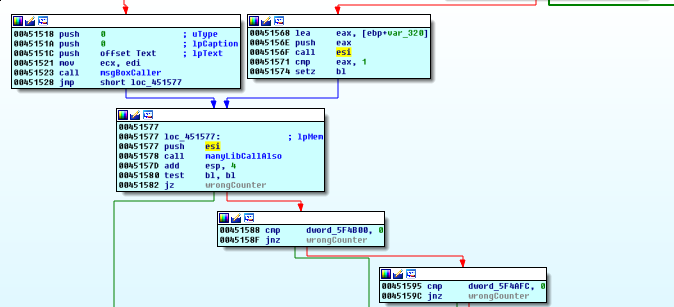

By this point, you know the drill. We check the xrefs and rename what we can, then we scroll around and see if we can quickly label some functions based on significant API calls they make.

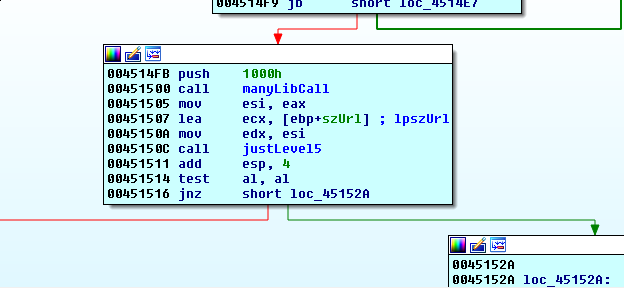

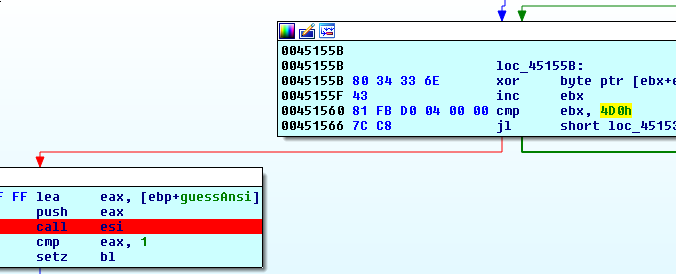

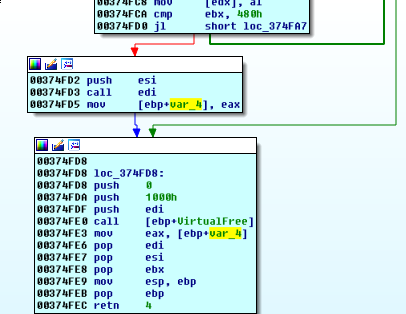

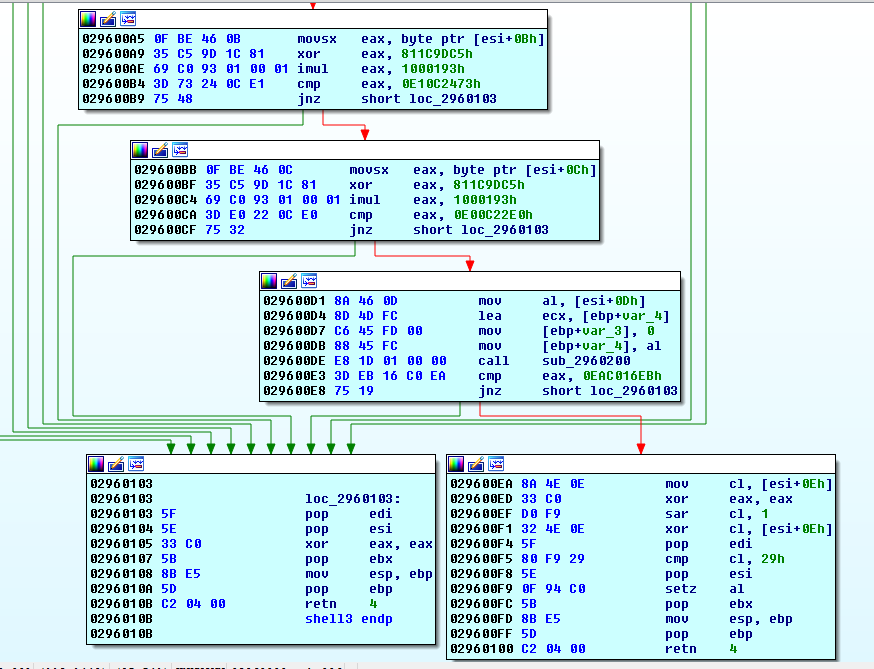

Scrolling around a little and it seems that the Level 5 code isn’t going to do much. However, this call esi stands out a little bit. We set a breakpoint here and go back to find where var_320 comes from.

We take this opportunity to do a bit of skimming to see if anything stands out. Along the way, we make note of this function unique to Level 5 that may be using a URL.

The false branch will display a message box with the Text “NEEDS MORE INTERNET”

PANW:00451518 push 0 ; uType

PANW:0045151A push 0 ; lpCaption

PANW:0045151C push offset Text ; lpText

PANW:00451521 mov ecx, edi

PANW:00451523 call msgBoxCaller

PANW:00451528 jmp short loc_451577

Scrolling back up to find the var_320 buffer, it seems we finally pay enough attention to realize that lib2CallAlso provides an ansi version of a unicode string that is passed in.

We do a little bit of renaming:

PANW:00451420 lea eax, [ebp+wideCharGuess]

PANW:00451426 push eax ; lpWideCharStr

PANW:00451427 lea eax, [ebp+guessAnsi]

PANW:0045142D push eax ; int

PANW:0045142E call wideToAnsi

PANW:00451433 xor bl, bl

and it looks like the bytes on the stack will potentially end up as a URL.

The call to esi will take the ansi version of our input as an argument, and it is not read or accessed elsewhere until what is presumably the flag generating routine (happens after the anti-debug cascade).

Since it is the final level, we might as well take a moment to appreciate the heavy lifting that scylla hide has been doing for us. Let’s investigate what this anti-debug cascade is all about.

Double clicking the dword, then examining the xrefs with x, we see that there is only one place where the first dword is written to.

We double click it and we see the dark secrets of this dword:

Scrolling up to the start of this section of code, we press p to help IDA help us. We take a quick look around, and head back to the task at hand.

We step through, watching a bit of the decryption loop just for fun, until we hit the call to the justLevel5 function (which we now have a better name for, but…it’s not a big concern for this binary).

We take a look at the URL being passed in:

Stack[00000C90]:0018EA24 aHttpsRaw_githubuserco db 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/edix/sedocllehs/master/1.bin',0

and it seems like a good opportunity to see what other things we might expect

$ python -c 'print "sedocllehs"[::-1]'

shellcodes

Naturally, we download all three:

$ for i in {1..3}; do wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/edix/sedocllehs/master/$i.bin; done

It appears to be encrypted:

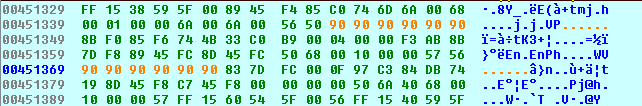

$ xxd 1.bin | head

00000000: 3b9c 9f94 fa5b 5841 41ae d41c 371f b452 ;....[XAA...7..R

00000010: ea17 0b17 16ff d515 6e17 ca24 9e4d 959c ........n..$.M..

00000020: e6ff e915 6e17 ca85 e7b9 449e 53ef 9b9a ....n.....D.S...

This is likely what the loop will take care of when we return from downloading this.

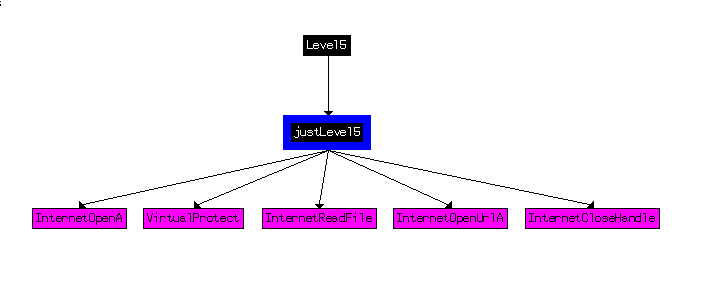

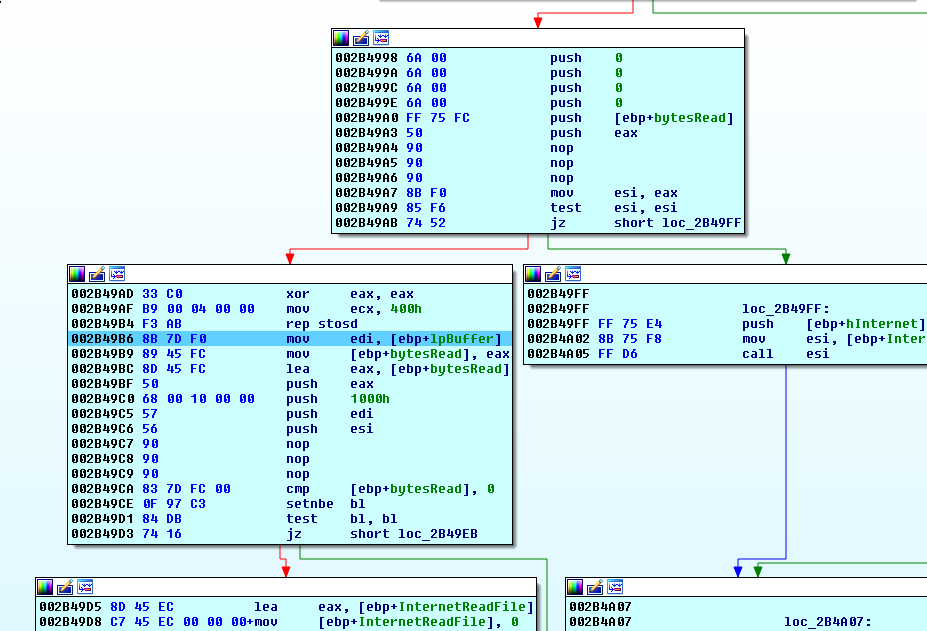

We take a look inside the justLevel5 function and a quick user xrefs chart tells the story:

A little bit of reading on MSDN would clear things up if it’s not clear enough. We step through…and we get an exception on InternetOpenUrlA. Not entirely sure why, but that’s ok, we have the bytes we need. (Note that x64dbg does not have this issue)

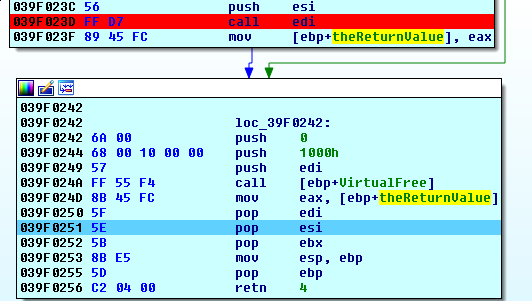

We prepare for a bit of binary surgery.

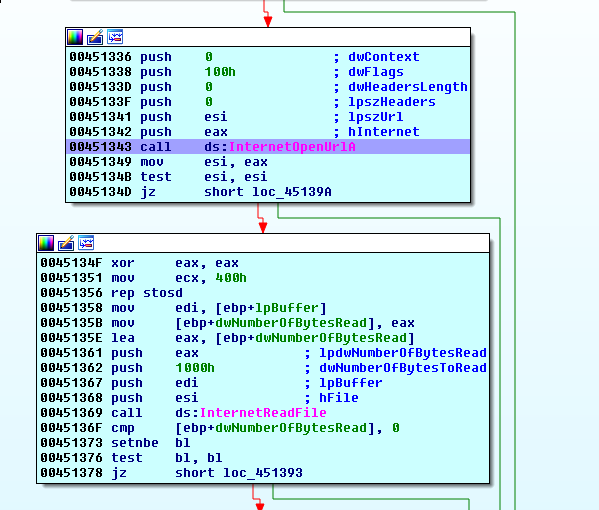

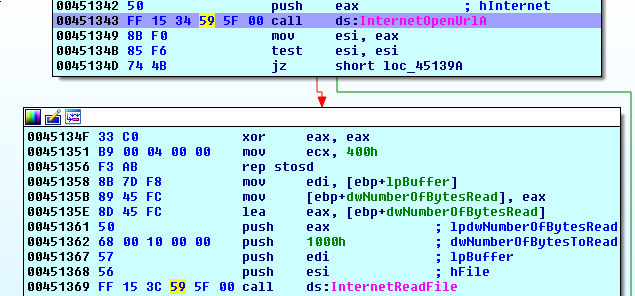

We launch revfest.exe again and input all the passwords. Just before submitting the Level 5 guess, we set a breakpoint on the call to InternetOpenUrlA and attach with IDA.

Since it returns a handle that will be used by InternetReadFile, we will have to deal with this call as well.

It would probably be a good idea to have some handy patching capability at this point, but then we’d have to restart IDA and we gotta go fast (by doing things in a slower way?).

We turn on the opcodes so we can be sure of what we’re patching in the hex-view:

Then we nop these bytes out in the hex-view with some F2 editing magic.

PANW:00451336 6A 00 push 0 ; dwContext

PANW:00451338 68 00 01 00 00 push 100h ; dwFlags

PANW:0045133D 6A 00 push 0 ; dwHeadersLength

PANW:0045133F 6A 00 push 0 ; lpszHeaders

PANW:00451341 56 push esi ; lpszUrl

PANW:00451342 50 push eax ; hInternet

PANW:00451343 90 nop

PANW:00451344 90 nop

PANW:00451345 90 nop

PANW:00451346 90 nop

PANW:00451347 90 nop

PANW:00451348 90 nop

PANW:00451349 8B F0 mov esi, eax

PANW:0045134B 85 F6 test esi, esi

PANW:0045134D 74 4B jz short loc_45139A

Since eax already has a value in it, then we are not concerned with faking a return value here.

We step through to the InternetReadFile call and read carefully:

PANW:0045134F 33 C0 xor eax, eax

PANW:00451351 B9 00 04 00 00 mov ecx, 400h

PANW:00451356 F3 AB rep stosd

PANW:00451358 8B 7D F8 mov edi, [ebp+lpBuffer]

PANW:0045135B 89 45 FC mov [ebp+dwNumberOfBytesRead], eax

PANW:0045135E 8D 45 FC lea eax, [ebp+dwNumberOfBytesRead]

PANW:00451361 50 push eax ; lpdwNumberOfBytesRead

PANW:00451362 68 00 10 00 00 push 1000h ; dwNumberOfBytesToRead

PANW:00451367 57 push edi ; lpBuffer

PANW:00451368 56 push esi ; hFile

PANW:00451369 90 nop

PANW:0045136A 90 nop

PANW:0045136B 90 nop

PANW:0045136C 90 nop

PANW:0045136D 90 nop

PANW:0045136E 90 nop

PANW:0045136F 83 7D FC 00 cmp [ebp+dwNumberOfBytesRead], 0

PANW:00451373 0F 97 C3 setnbe bl

PANW:00451376 84 DB test bl, bl

PANW:00451378 74 19 jz short loc_451393

The dwNumberOfBytesRead is something we will have to set, as well as filling the lpBuffer with the 1.bin bytes. It would make sense to set the number of bytes read to the number of bytes in 1.bin.

$ wc -c 1.bin

1232 1.bin

$ pcalc 1232

1232 0x4d0 0y10011010000

and the decryption loop waiting for us outside of this function would agree:

We note that the address of this variable is still in eax, click in the lower hex-dump window, press g and type eax.

Keeping in mind the little endian byte ordering, we enter a nice, obvious, intuitive: d0 04

Now, we prepare to copy the 1.bin shellcode into lpBuffer.

We get the address of the lpBuffer:

Stack[00000F10]:0018E3A4 dd offset unk_374D40

Now we can easily modify the buffer copy script from Level 3 (not stage 3 in level 5) to make this work:

def PatchArr(dest, str):

for i, c in enumerate(str):

idc.PatchByte(dest+i, ord(c));

# usage: patchArr(start address, string of bytes to write)

shell1 = open('1.bin', 'rb').read()

PatchArr(0x374D40, shell1)

RefreshDebuggerMemory()

A quick confirmation of our work:

debug024:00374D40 unk_374D40 db 3Bh ; ; ; DATA XREF: Stack[00000F10]:0018E3A4o

debug024:00374D41 db 9Ch ; £

debug024:00374D42 db 9Fh ; ƒ

debug024:00374D43 db 94h ; ö

debug024:00374D44 db 0FAh ; ·

debug024:00374D45 db 5Bh ; [

debug024:00374D46 db 58h ; X

and we are on our way.

We run until our breakpoint at the call to esi noting that this rabbit hole will probably be our last, as the anti-debug cascade begins with a test of the return value from this call to esi.

We examine esi:

debug122:00374D40 unk_374D40 db 55h ; U ; DATA XREF: Stack[00000F10]:0018E3A4o

debug122:00374D41 db 8Bh ; ï

debug122:00374D42 db 0ECh ; 8

debug122:00374D43 db 83h ; â

debug122:00374D44 db 0ECh ; 8

debug122:00374D45 db 4Ch ; L

It is our successfully decrypted shellcode. We could dump this shellcode and analyze it a few different ways…(e.g., wrap it in its own executable, emulate it using miasm), but perhaps that’ll be another blog post.

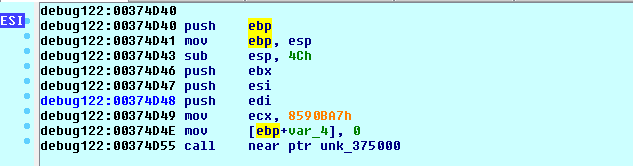

We click on the first byte of our shellcode, and define it as code c, then let IDA know it is a function with p. Before jumping into a CFG, we scroll down to see if there are other functions we missed as the

debug122:00374D55 call near ptr unk_375000

seems to suggest.

It seems worth our while to make sure we scroll through 0x4D0 bytes looking for more code.

$ pcalc 0x374d40+0x4d0

3625488 0x375210 0y1101110101001000010000

Taking a look at the first function, we see a familiar pattern:

This looks like it will decrypt some import names, then store them in variables/registers to call them.

We step through and rename the variables with the new information, being a little careful with the call

debug122:00374D73 push 1F4h

debug122:00374D78 mov [ebp+VirtualFree], eax

debug122:00374D7B call esi ; Sleep

debug122:00374D7D mov eax, large fs:18h

debug122:00374D83 mov ecx, 0A0568251h

debug122:00374D88 mov esi, [eax+30h]

debug122:00374D8B mov bl, [esi+2]

debug122:00374D8E call importDecrypt

debug122:00374D93 mov edi, eax

debug122:00374D95 call edi ; IsDebuggerPresent

debug122:00374D97 mov ecx, eax

debug122:00374D99 cmp bl, 1

debug122:00374D9C jz loc_374FEF

Then we spot our arg0, we rename it and note the string length calculation loop:

So we now have one important constraint on our input, it must be 0xF bytes in length. Otherwise, we go to a fail block that guarantees a return with a zero in eax.

We have already established that when we come out of this rabbit hole, Level 5’s main function demands a 1 for success.

PANW:00451568 lea eax, [ebp+guessAnsi]

PANW:0045156E push eax

PANW:0045156F call esi

PANW:00451571 cmp eax, 1

PANW:00451574 setz bl

Examining the other obvious endpoint for this function, we might venture a guess that this rabbit hole goes a little deeper:

$ wc -c 2.bin

1152 2.bin

$ pcalc 1152

1152 0x480 0y10010000000

Not that binary surgery isn’t fun, but perhaps we should take this opportunity to patch our input to the required length:

0018E5D0 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 6A 6B 6C 6D 6E 6F 00 abcdefghijklmno.

A successful length check leads us to another potential misstep:

debug122:00374DE2 movsx eax, dl

debug122:00374DE5 xor eax, 59h

debug122:00374DE8 lea eax, [eax+eax*2]

debug122:00374DEB cmp eax, 3Fh

debug122:00374DEE jnz badBloc

So the first byte of our input, xor’d with 0x59, multiplied by 3…should equal 0x3F:

>>> chr((0x3F/3)^0x59)

'L'

>>> hex(ord('L'))

'0x4c'

We apply a patch and note that this math doesn’t really hurt at all.

debug122:00374DF4 movsx eax, byte ptr [esi+1]

debug122:00374DF8 xor eax, 0CBh

debug122:00374DFD lea eax, [eax+eax*2]

debug122:00374E00 add eax, eax

debug122:00374E02 cmp eax, 3FCh

debug122:00374E07 jnz badBlock

>>> hex((0x3FC/6)^0xCB)

'0x61'

La…

>>> hex(len("Labyrenth_2017!"))

'0xf'

…maybe?

It’s a decent placeholder, and may require less patching later on.

def PatchArr(dest, str):

for i, c in enumerate(str):

idc.PatchByte(dest+i, ord(c));

# usage: patchArr(start address, string of bytes to write)

PatchArr(0x18E5D0, "Labyrenth_2017!")

RefreshDebuggerMemory()

A little more light math (after a careless F9, and having to restart this debugging run):

debug111:002B460D mov bl, [esi+2]

debug111:002B4610 movsx eax, bl

debug111:002B4613 xor eax, 44h

debug111:002B4616 shl eax, 2

debug111:002B4619 xor eax, 4Ch

debug111:002B461C cmp eax, 0D4h

debug111:002B4621 jnz badBlock

>>> hex(((0xD4 ^ 0x4C) / 4) ^ 0x44)

'0x62'

debug111:002B4627 mov dh, [esi+3]

debug111:002B462A movsx eax, dh

debug111:002B462D lea ecx, ds:0[eax*8]

debug111:002B4634 sub ecx, eax

debug111:002B4636 xor ecx, 301h

debug111:002B463C cmp ecx, 4Eh

debug111:002B463F jnz badBlock

>>> hex((0x4e^0x301)/7)

'0x79'

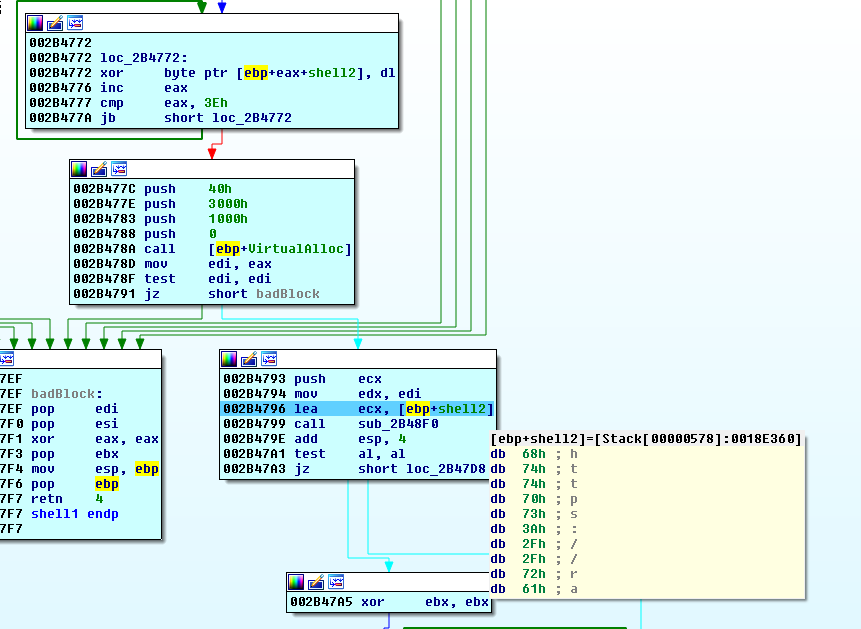

After these checks, we start getting into some ugly stuff…but none of it seems to be using our input, so we can step through until we reach these blocks:

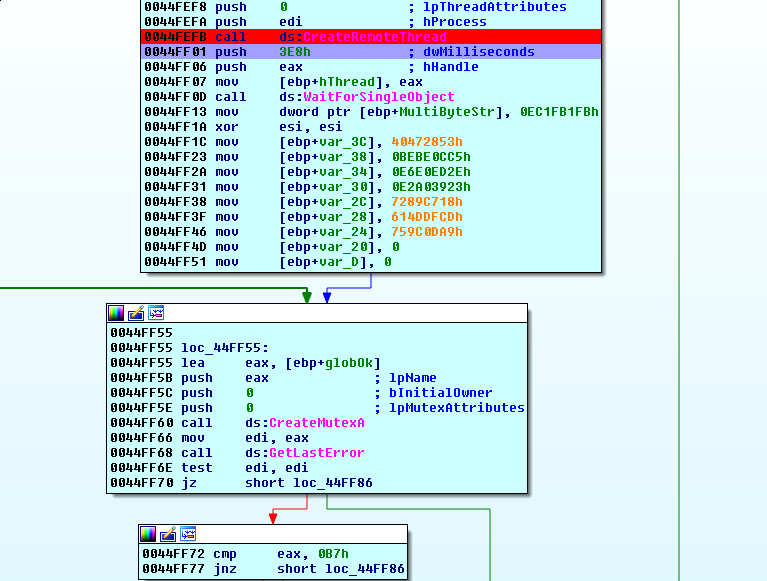

Now the 2.bin URL is being passed into a function. Looking ahead, it seems that this is the same situation as the Level 5 main code that launched this first stage.

We step into this function and move slowly as we rename, and confirm this idea. We will likely perform some more binary surgery.

Noting the arguments passed to the InternetReadFile function, we rename the variables properly and perform the next operation:

def PatchArr(dest, str):

for i, c in enumerate(str):

idc.PatchByte(dest+i, ord(c));

# usage: patchArr(start address, string of bytes to write)

shell2 = open('2.bin', 'rb').read()

PatchArr(0x39F0000, shell2)

RefreshDebuggerMemory()

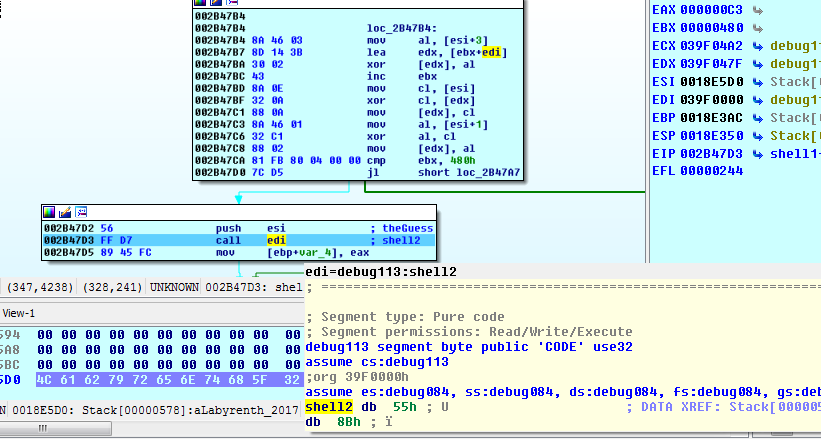

It seems we overlooked something important during the surgery in how the registers/stack is being managed and so we get an exception when attempting to xor al with [edx]:

debug111:002B47B4 loc_2B47B4:

debug111:002B47B4 8A 46 03 mov al, [esi+3]

debug111:002B47B7 8D 14 3B lea edx, [ebx+edi]

debug111:002B47BA 30 02 xor [edx], al

debug111:002B47BC 43 inc ebx

debug111:002B47BD 8A 0E mov cl, [esi]

debug111:002B47BF 32 0A xor cl, [edx]

debug111:002B47C1 88 0A mov [edx], cl

debug111:002B47C3 8A 46 01 mov al, [esi+1]

debug111:002B47C6 32 C1 xor al, cl

debug111:002B47C8 88 02 mov [edx], al

debug111:002B47CA 81 FB 80 04 00 00 cmp ebx, 480h

debug111:002B47D0 7C D5 jl short loc_2B47A7

Studying the logic, it makes sense that esi should be pointing to our guessed password, and edi which is being indexed with the loop counter that loops until 0x480 is a pointer to our shell2 buffer. Setting these values, then manually editing EIP to point to the beginning of this basic block, we continue.

and all is well…for now.

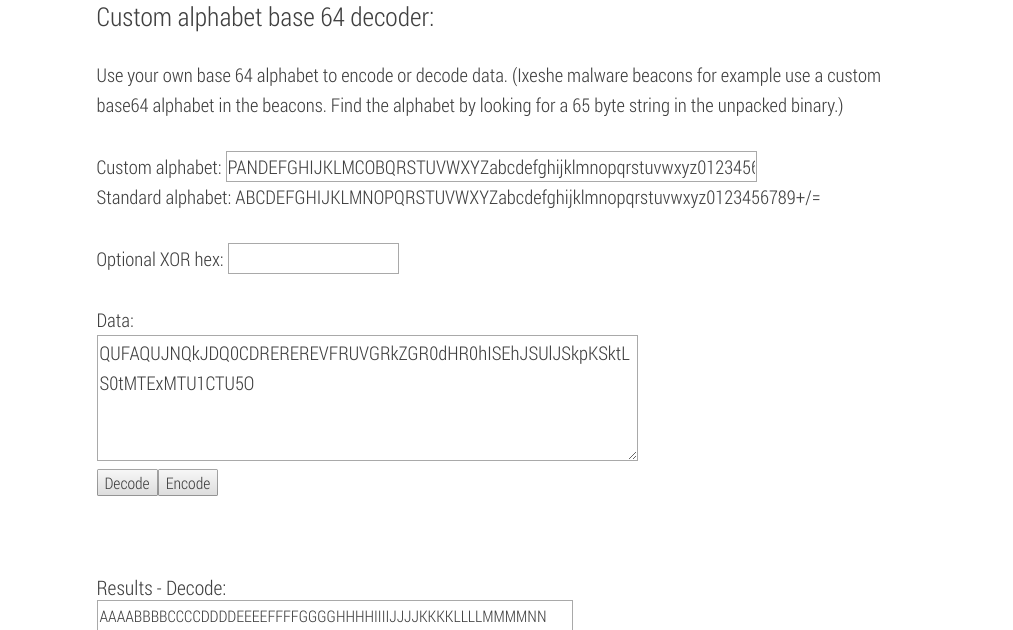

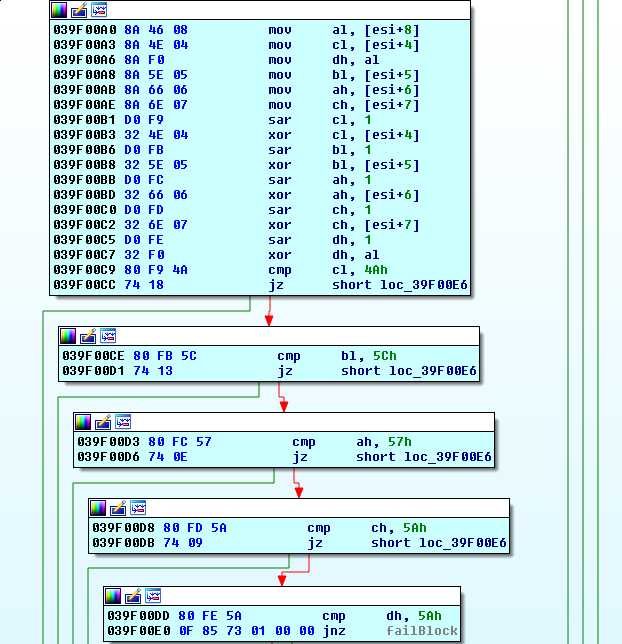

Stepping into stage 2, it doesn’t take long to recognize what various blocks are doing. It is very similar code to stage 1. We focus our attention on the next phase of the password checking routine:

Essentially, we want x^(x/2) to equal 0x4A, 0x5C, 0x57, 0x5A, and 0x5A.

#!/usr/bin/env python

targetChars = [0x4A, 0x5C, 0x57, 0x5A, 0x5A]

for target in targetChars:

for x in range(0x20, 0x7F):

if x^(x/2) == target:

print "Target: %s - X: - %s" % (chr(target), chr(x))

$ ./stage2.py

Target: J - X: - s

Target: \ - X: - h

Target: W - X: - e

Target: Z - X: - l

Target: Z - X: - l

and we get another 5 characters.

We patch our guess with the new information:

0018E5D0 4C 61 62 79 73 68 65 6C 6C 5F 32 30 31 37 21 00 00 00 00 00 Labyshell_2017!.....

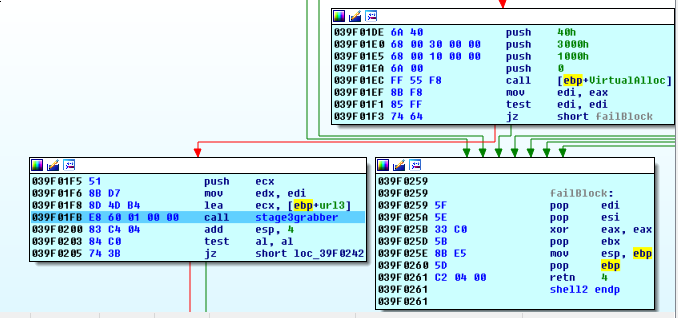

We then prepare for what may be the last stage:

We step into stage3grabber and perform the surgery again.

$ wc -c 3.bin

688 3.bin

$ pcalc 688

688 0x2b0 0y1010110000

0x2b0 bytes this time…that could be good news.

Based on the way the registers will be used in the decryption loop, we remember to make sure that esi points to our guess string, and EDI points to the lpBuffer where we pasted the 3.bin bytes:

During our initial cleanup routine, we see that there is a code xref to these bytes…

debug114:02960200 unk_2960200 db 8Bh ; ï ; CODE XREF: shell3+DEp

debug114:02960201 db 0D1h ; -

debug114:02960202 db 83h ; â

debug114:02960203 db 0C8h ; +

debug114:02960204 db 0FFh

debug114:02960205 db 8Ah ; è

debug114:02960206 db 0Ah

debug114:02960207 db 84h ; ä

it doesn’t look like a standard function prologue, but it is indeed another function. We define it as code and tell IDA it is a function.

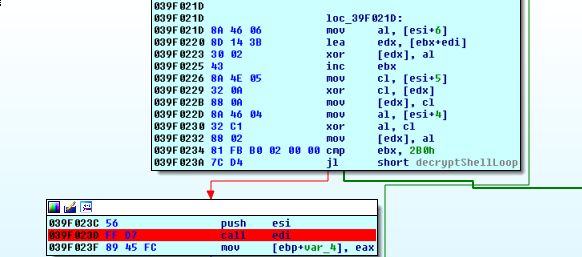

Looking around shell3’s main, the code follows a familiar sequence, but we step anyway just in case there are tricks in this last stage.

Examining the two basic blocks that return from this function, we spot the final check of our input in the block on the right:

debug114:029600EA 8A 4E 0E mov cl, [esi+0Eh]

debug114:029600ED 33 C0 xor eax, eax

debug114:029600EF D0 F9 sar cl, 1

debug114:029600F1 32 4E 0E xor cl, [esi+0Eh]

debug114:029600F4 5F pop edi

debug114:029600F5 80 F9 29 cmp cl, 29h

debug114:029600F8 5E pop esi

debug114:029600F9 0F 94 C0 setz al

debug114:029600FC 5B pop ebx

debug114:029600FD 8B E5 mov esp, ebp

debug114:029600FF 5D pop ebp

debug114:02960100 C2 04 00 retn

It looks like we are just about done.

We do some quick python math to start filling out the remaining characters in our password:

debug114:02960079 0F BE 46 09 movsx eax, byte ptr [esi+9]

debug114:0296007D 35 C5 9D 1C 81 xor eax, 811C9DC5h

debug114:02960082 69 C0 93 01 00 01 imul eax, 1000193h

debug114:02960088 3D 52 2C 0C E6 cmp eax, 0E60C2C52h

debug114:0296008D 75 74 jnz short failBlock

Noting that the xor and imul operands are the same allows us to save some code:

#!/usr/bin/env python

xorConst = 0x811C9DC5

imulConst = 0x1000193

winChars = []

def calcAbyte(target):

for c in range(0x20, 0x7F):

calced = (((c ^ xorConst) & 0xFFFFFFFF) * imulConst) & 0xFFFFFFFF

if calced == target:

winChars.append(c)

return c

targetHashes = [0xE60C2C52, 0xEA0C329E, 0xE10C2473, 0xE00C22E0]

for target in targetHashes:

calcAbyte(target)

print ''.join(map(chr, winChars))

print map(hex, winChars)

and we have another 4 bytes:

$ ./tinyBrute.py

code

['0x63', '0x6f', '0x64', '0x65']

Before we jump into the guess[0xD] calculator:

debug114:029600D1 8A 46 0D mov al, [esi+0Dh]

debug114:029600D4 8D 4D FC lea ecx, [ebp+guessAt0xD]

debug114:029600D7 C6 45 FD 00 mov [ebp+initTo0], 0

debug114:029600DB 88 45 FC mov [ebp+guessAt0xD], al

debug114:029600DE E8 1D 01 00 00 call differentPrologueCalcs0xD

debug114:029600E3 3D EB 16 C0 EA cmp eax, 0EAC016EBh

debug114:029600E8 75 19 jnz short failBlock

we might as well get the last easy calc out of the way:

debug114:029600EA 8A 4E 0E mov cl, [esi+0Eh]

debug114:029600ED 33 C0 xor eax, eax

debug114:029600EF D0 F9 sar cl, 1

debug114:029600F1 32 4E 0E xor cl, [esi+0Eh]

debug114:029600F4 5F pop edi

debug114:029600F5 80 F9 29 cmp cl, 29h

debug114:029600F8 5E pop esi

debug114:029600F9 0F 94 C0 setz al

debug114:029600FC 5B pop ebx

debug114:029600FD 8B E5 mov esp, ebp

debug114:029600FF 5D pop ebp

debug114:02960100 C2 04 00 retn 4

al will be set if cl is 0x29, therefore:

>>> for c in range(0x20, 0x7F):

... if c/2^c == 0x29:

... print hex(c)

... print chr(c)

...

0x31

1

Labyshellcode?1

We patch our guess bytes with this information, then we step inside differentPrologue.

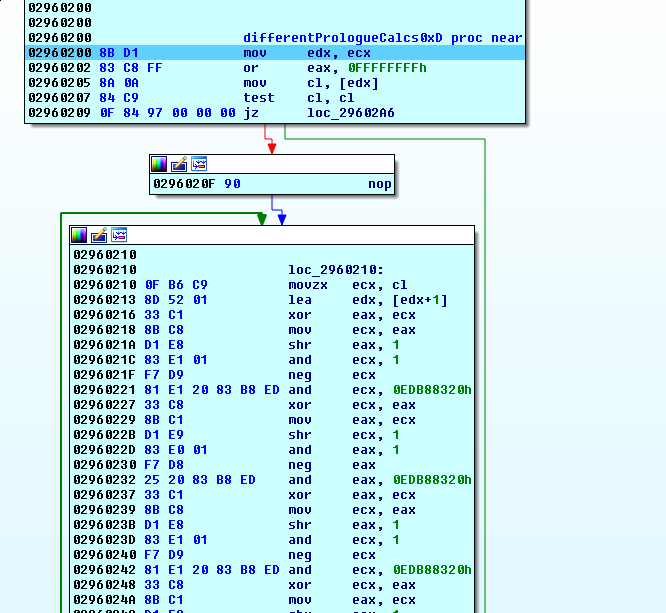

The repeated use of the 0xEDB88320 seems interesting. Findcrypt did not have a chance to examine this code, since it did not exist yet. We opt for a google search instead.

The first result talks about CRC32. Searching for CRC32 python, we find that binascii provides this.

Noting that when this function returns, we’ll find this:

debug114:029600DE E8 1D 01 00 00 call differentPrologueCalcs0xD

debug114:029600E3 3D EB 16 C0 EA cmp eax, 0EAC016EBh

debug114:029600E8 75 19 jnz short failBlock

…it seems that we might as well try our luck with CRC32ing the printable ascii range (reasonable assumption based on textbox input and all that we’ve seen so far).

>>> import binascii

>>> for c in range(0x20, 0x7F):

... if (~binascii.crc32(chr(c)) ^ 0x4c11db7) == 0xEAC016EB:

... print chr(c)

... print hex(c)

...

nothing? Something must be wrong.

signedness and python

>>> for c in range(0x20, 0x7F):

... a = binascii.crc32(chr(c)) & 0xFFFFFFFF

... b = a ^ 0x4c11db7

... if b == 0xeac016eb:

... print chr(c)

... print hex(c)

...

$

0x24

Labyshellcode$1 it is.

Our al gets set:

debug114:029600F5 80 F9 29 cmp cl, 29h

debug114:029600F8 5E pop esi

debug114:029600F9 0F 94 C0 setz al

debug114:029600FC 5B pop ebx

debug114:029600FD 8B E5 mov esp, ebp

debug114:029600FF 5D pop ebp

debug114:02960100 C2 04 00 retn

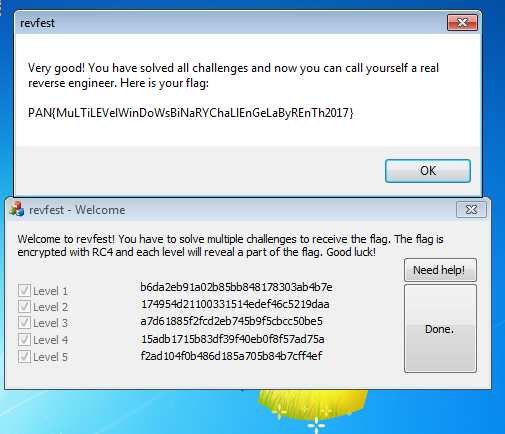

and we step through the end of each stage, watching memory being freed and our succesful return value passed in eax

However, we did forget to deal with the after effects of the binary surgery in Level 5’s main. We have a few choices. I opt for a trip down memory lane. We exit out of this process, start it again with no debuggers or IDA involved, and enjoy submitting the flags one by one.

…we’re certainly on the way, at least.

References:

- Practical Malware Analysis

- IDA docs

- Function prologue

- GetWindowText

- FindCrypt

- Resource Hacker

- Stegsolve

- zsteg

- Hooked on mnemonics

- stosd

- CreateMutexA

- GetLastError

- Error Codes

- Base64

- Overclock.net forums

- Base64 length

- malwaretracker base64 decoder

- xamiel github

- FNV-64 hash implementation

- Fowler/Noll/Vo hash

- Keypatch

- setz

- binascii

- Stackoverflow CRC32 Python - 1

- Stackoverflow CRC32 Python - 2

- Shellcode2exe

- miasm

- IDA Stealth

- x64dbg