Minesweeper: 3 Lives and a Mine detector (Part 1, Reversing the Needful in an enLighthoused way)

Intro

In this post, we’ll begin working on a project to implement a lives feature in Minesweeper, as well as produce an answer key for a given game board. The objective is:

- grant the user an additional two attempts to clear the board

- generate an answer key containing an ascii representation of the game board’s mine locations

The idea is to pick a project to exercise some reverse engineering, and game hacking skills. The latter of which I have just begun to acquire with this excellent use of your time: Game Hacking. A lot of the things presented in this book will be familiar to malware analysts, and can help improve your skill-set.

Additionally, we’ll take a less conventional approach to this reversing task (see the other blog posts on this site for a more traditional bottom-up approach). We’ll being using Markus Gaasedelen’s very excellent code coverage explorer plugin, Lighthouse, to efficiently guide our reversing efforts.

Step 0: Familiarize ourselves with the game and think about how the code may have been written.

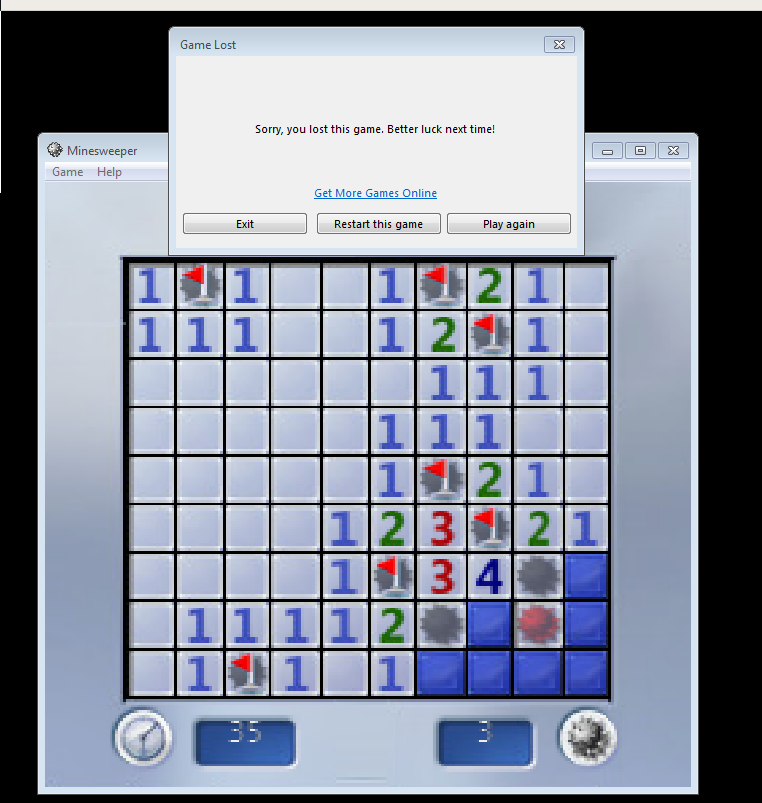

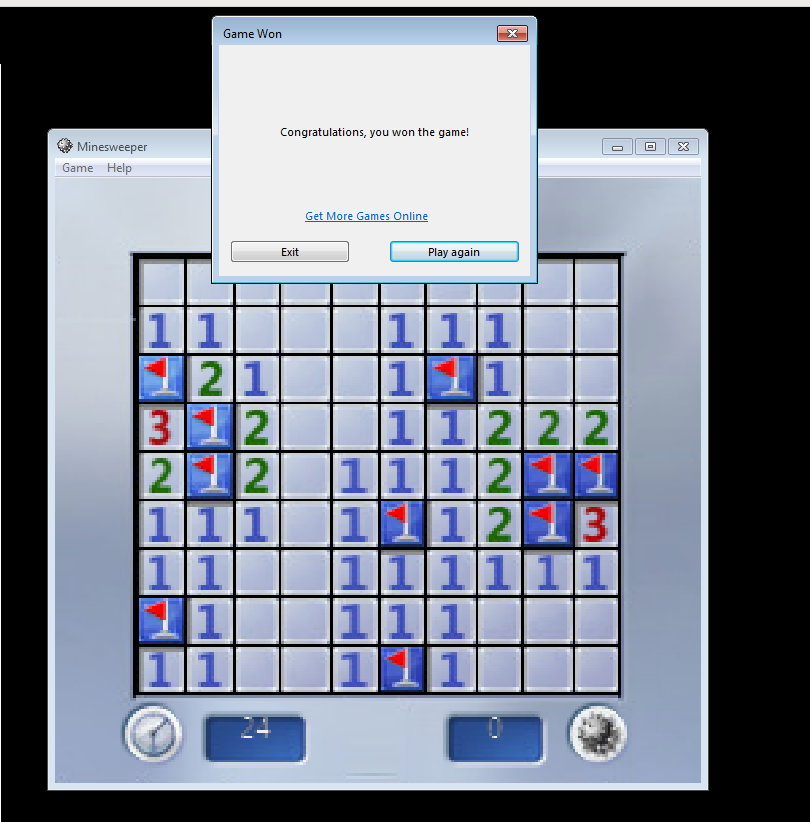

It’s worth playing through a game on beginner to observe the win state, and purposely losing a game to observe the losing state.

Observations and notes:

- there’s a timer

- starts when first (any) tile is revealed

- there’s a mine count

- starts at 10

- decreases by 1 for every tile that is flagged (right-click)

- the displayed mine count is not validated and seems to only correspond to number of flags placed on tiles

- tiles can be in one of several states

- flagged (tile believed to contain a mine)

- question mark (status unknown)

- revealed

- blank

- numbered

- contained a mine that was tripped (mine with red background)

- contained a mine

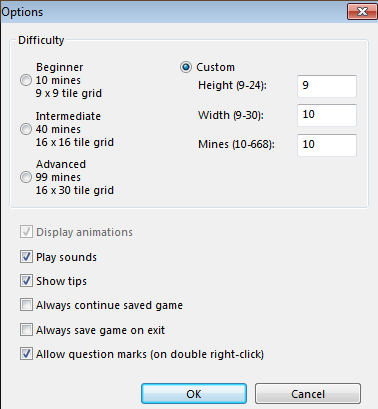

- game board can be modified

- mine count [10, 668]

- rows [9, 24]

- columns [9, 30]

- presets “Beginner”, “Intermediate”, “Advanced”

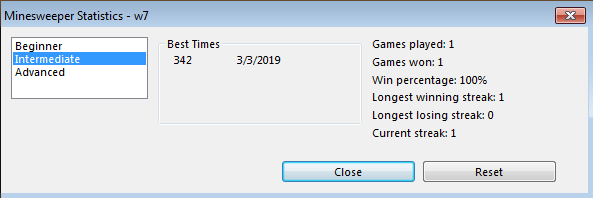

- there’s a statistics menu

- games played

- games won

- etc.

- game play

- when tile revealed

- timer starts if first time a tile is revealed

- revealed tile takes on one of the states listed above

- numbered tile indicated number of adjacent mines

- based on revealed tile data

- flag definite mine locations (if any)

- clear tiles that cannot contain mines (if any)

- when tile revealed

Ok, with a bit of an idea of what we’d expect from the code, we can start with some basic static analysis…

Step 1: Initial triage and recon

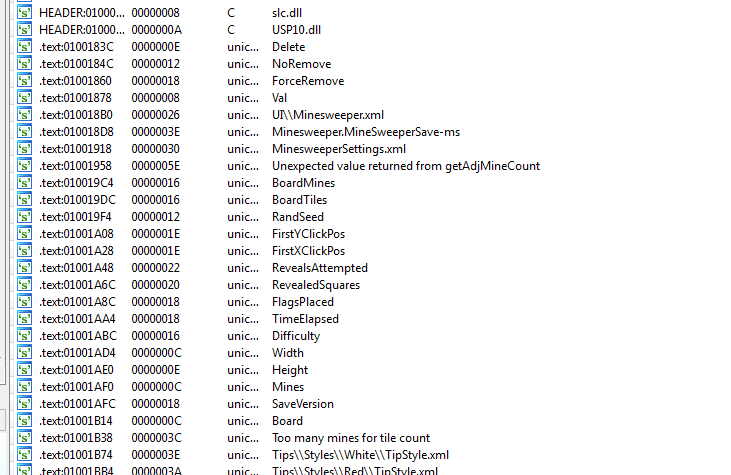

Looking at the strings is usually a great place to start…

The file we’re running strings on is MineSweeper.exe (SHA1:02a4c588126b4e91328a82de93a3ea43e16bf129).

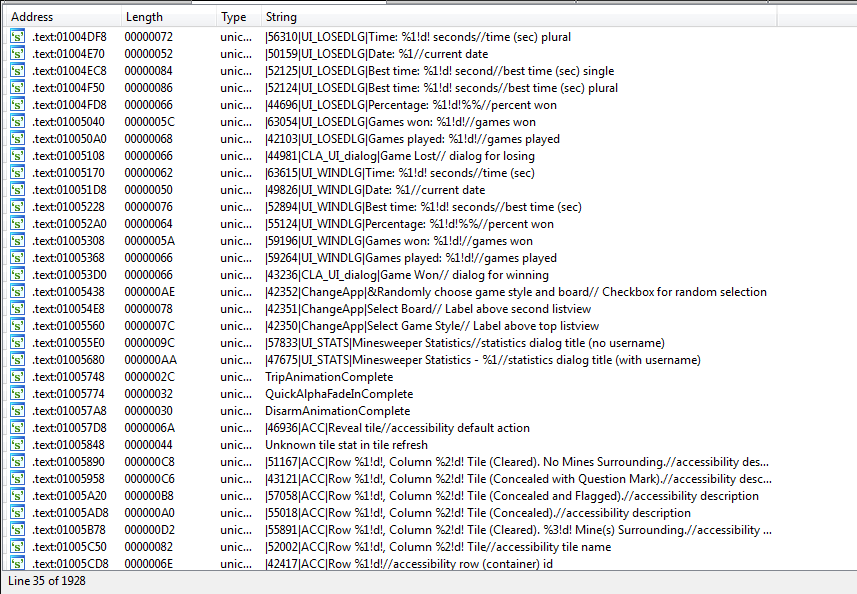

Unfortunately, there is a lot of noise here. Loading the file into IDA, to give us a more interactive view of the strings:

Some things stand out right away:

Knowing more about BoardMines definitely sounds like a good idea, given our secondary objective of generating an answer key for mine locations. However, the primary objective is to provide a couple more chances to get things right. A little more examination of the strings reveals the following:

A dialog for winning, and a dialog for losing (would have been a good idea to search for the strings we saw in the dialogs we observed previously). Also interesting are the strings that indicate the tile states and coordinates. Though there doesn’t seem to be a string for a mine having been clicked.

Ultimately, we want to find the point where the game decides you have made a bad move and then tries to end you. We’d definitely dig deeper into the strings here and start trying to build our understanding, renaming as we go. However, we’re not really trying to understand all of this code, we want to understand only enough to achieve our objectives. So we’re going to try a different approach here.

One approach may be to diff the code coverages between games where a mine was triggered, and a game where it wasn’t…with no other actions being different. We should be able to identify the code responsible for ending you(r game). We might be able to get away with studying just this code.

Let’s try that:

We can collect code coverage data using the DynamoRIO dynamic binary instrumentation framework as explained here:

C:\Users\w7\Desktop\DynamoRIO-Windows-7.0.0-RC1>bin32\drrun.exe -t drcov -- "c:\

Program Files\Microsoft Games\Minesweeper\MineSweeper.exe"

The MineSweeper process is launched, we click the first square, then click a safe square for the next move. Then exit.

We repeat the process, this time making sure that the second click will hit a mine.

For those interested in learning more about DBI (and other binary analysis topics). I highly recommend picking up a copy of Practical Binary Analysis to read about this topic and more. This is another excellent release from nostarch press, and I can’t recommend it highly enough. Alternatively this blog post gives a nice overview as well.

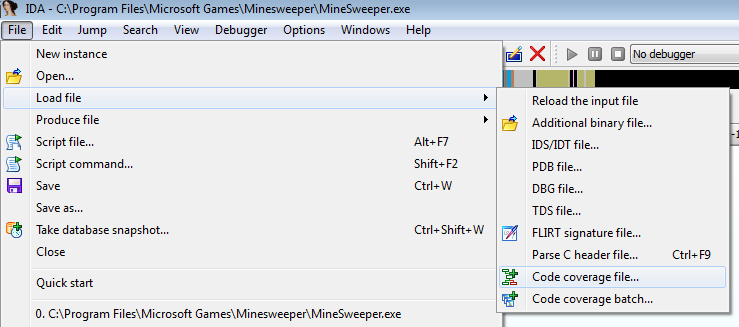

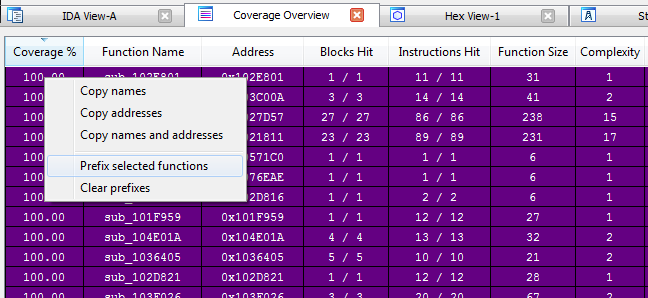

We’ll then load this data into IDA using the Lighthouse plugin:

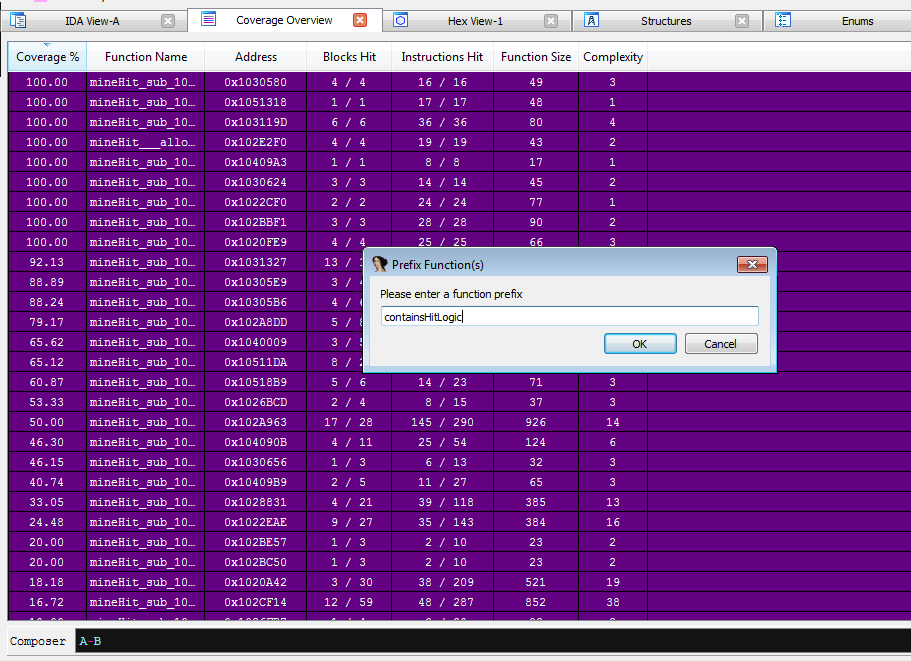

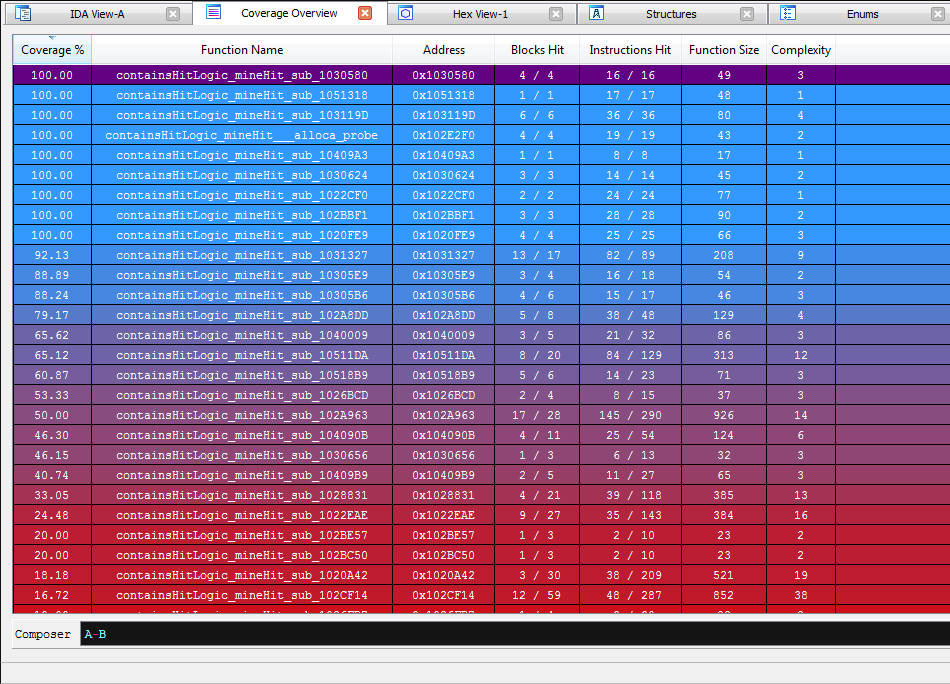

Here’s how we can make use of it:

- Sort coverage from highest to lowest

- Select all functions that have a coverage greater than 0.00

- Right-click to add a prefix to these functions, e.g., “mineHit”

…but that’s quite a bit more code than we want to look at, so…we load the coverage for the game that didn’t hit a mine, and subtract it from the mineHit coverage.

This looks more manageable, and hopefully your mind is racing with possibilities. This is quite an excellent tool.

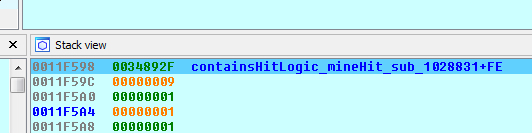

Let’s prefix these functions, “containsHitLogic”

Ok, so there’s still quite a bit of code here,

But now that we’re dealing with a smaller haystack, we can use the strings we made note of earlier in order to guide us.

Let’s see if we can work our way backwards from the tile state strings:

.text:01005890 a51167AccRow1DC: ; DATA XREF: containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_102CF14+179o

.text:01005890 unicode 0, <|51167|ACC|Row %1!d!, Column %2!d! Tile (Cleared). No Min>

.text:01005890 unicode 0, <es Surrounding.//accessibility description>,0

.text:01005958 a43121AccRow1DC: ; DATA XREF: containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_102CF14+168o

.text:01005958 unicode 0, <|43121|ACC|Row %1!d!, Column %2!d! Tile (Concealed with Q>

.text:01005958 unicode 0, <uestion Mark).//accessibility description>,0

.text:01005A1E align 10h

.text:01005A20 a57058AccRow1DC: ; DATA XREF: containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_102CF14+150o

.text:01005A20 unicode 0, <|57058|ACC|Row %1!d!, Column %2!d! Tile (Concealed and Fl>

.text:01005A20 unicode 0, <agged).//accessibility description>,0

Looks promising, let’s see what 102CF14 is all about.

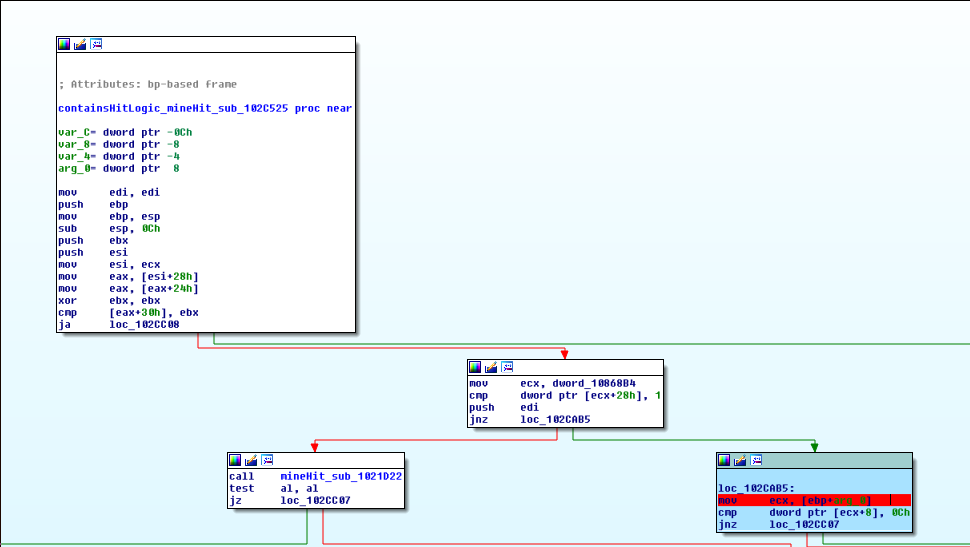

Keep in mind that the coloured basic blocks indicate the code that was executed only in the mine hit trace.

Let’s investigate calls to functions with a containsHitLogic prefix and see if any of the coloured blocks stand out.

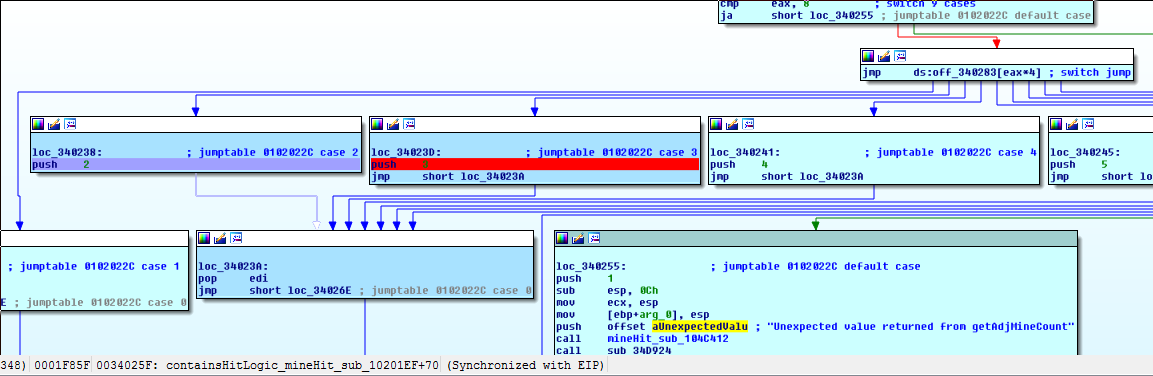

The different arguments leading us down the different branches may just be rendering different sprites (strings in the called functions give us a clue “Refresh” “Sprite”). It’s possible that this big switch function may be called after the mine hit decision has already been made.

We’ll rename this function, tileCases, because we’ll definitely want to come back and play with the rendering of sprites logic…it might not be too satisfying to have an extra life if the tile sprite did not reflect what had happened.

There really aren’t too many functions in our coverage with the “containsHitLogic”, perhaps we can try to establish a timeline by setting a breakpoint on the coloured basic blocks within these functions. We should be able to identify the first occurence of the code diverging from the non-losing code.

We’ll set breakpoints as follows:

- If a function has 100% coverage, set the breakpoint at the top of that function.

- Otherwise, set the breakpoint on the first basic block that is coloured. For example:

Automating this would be a good idea, but we can take this opportunity to gain an awareness of what these functions might look like and the strings they may reference. Consider it the equivalent of skimming a chapter to get a preview. We’ll get very familiar with some of this code afterwards.

With the breakpoints set, we can run the game and see who gets hit when.

We click to reveal the first tile and we hit a breakpoint. It wouldn’t make sense for the first click to ever be a mine, so let’s ignore this and let the program continue (disable the breakpoint instead of deleting it, so it can serve as a bookmark in case we’re wrong about this). We hit another seemingly insignificant breakpoint and continue.

The next breakpoint reveals an assumption in this process we did not account for:

The code coverage diff we are studying reveals code paths that were uniquely executed during the losing game. However, the non-losing game we compared against could have executed some of this code too. This switch statement appears to have determined how many mines are adjacent to our revealed tile. This is unlikely to be the only assumption we did not account for. We could generate more exhaustive and thorough sets of code coverage files to compare against, but in this case, we’ll get a lot of help from the dynamic analysis and it won’t be necessary.

tileCases is hit next. Recalling our earlier hypothesis that when we’re in tileCases the game is just rendering a state that has already been determined, we expect the game to render the result of our tile reveal (a blank square, or a number representing how many mines are adjacent to our tile).

Now might be a good time to study tileCases a little more. We note that there are 12 cases (and a default for an unknown state). This corresponds to our understanding of the possible states a tile can have, and the strings in the individual cases also spell this out:

- A sprite indicating [1, 8] adjacent mines

- Blank

- Flagged

- Question mark

- Unknown

Studying the function a little more, we see the following:

mov eax, [esi+18h]

inc eax

push eax

mov eax, [esi+1Ch]

inc eax

push eax ; char

push offset a52002AccRow1DC ; "|52002|ACC|Row %1!d!, Column %2!d! Tile//accessibility tile name"

call mineHit_sub_1050426

So perhaps a tile object is passed to this tileCases function. The object appears to store information about itself such as column and row position. That’s good to know. It’s tempting to think that if we study this object, it might also hold other information such as its mine state. I’ll save us some time and ignore this possibility.

Although there are other blocks in tileCases that were uniquely hit in our losing game, we should fully expect to miss them this time around based on our hypothesis that we cannot click on a mine as the first click. We can step through the rest of this function to confirm.

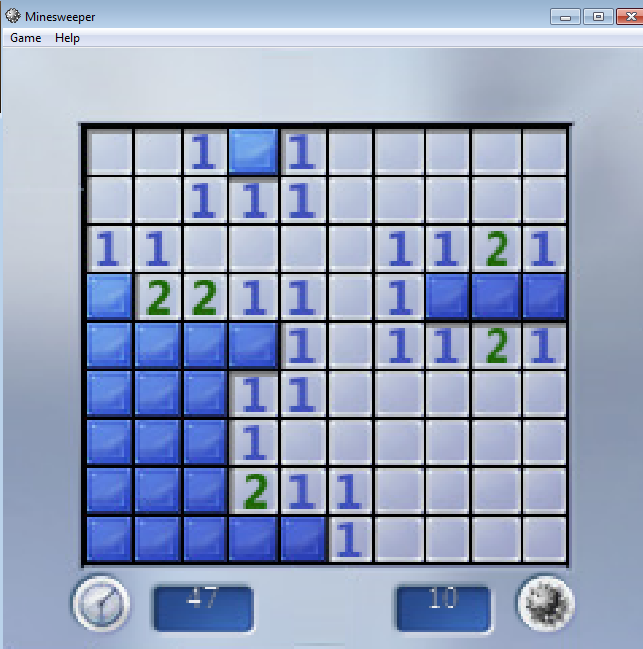

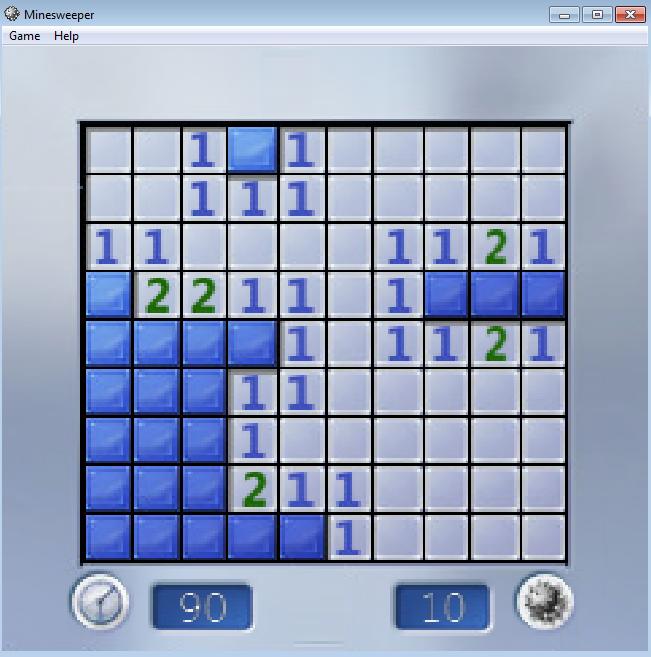

We move our tileCases breakpoint to the next uniquely hit block (after the switch statements). Continuing on, disabling breakpoints for this first click…we arrive at the following game board state:

Ok, let’s click a mine and see what we hit:

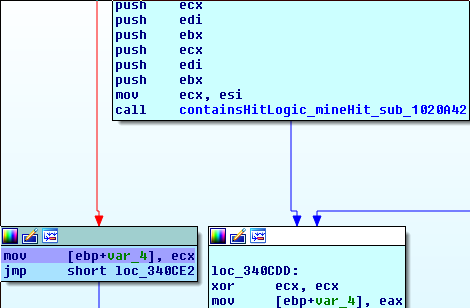

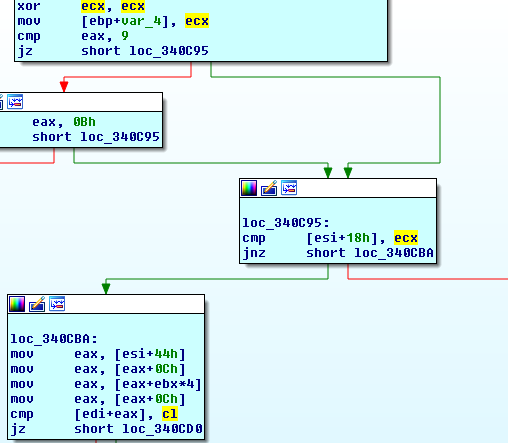

The first hit occurs in containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_1020C50. The coloured basic block is one that only gets hit when we’ve stepped on a mine, so we should understand the basic block that caused us to branch here:

mov eax, [esi+44h]

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

mov eax, [eax+ebx*4]

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

cmp [edi+eax], cl

jz short loc_340CD0

If we highlight cl, we can see that it was set to 0 (with the xor ecx, ecx operation) in the first basic block of this function.

(do ignore the branch targets and any other address references from this point forward, I did not rebase the program for this run but we’ll be more interested in what we’ve renamed and relative offsets anyway in part 2).

So, we can start digging into what the ugly bunch of dereferencing that leads to [edi+eax] is all about. Looking at the basic block that makes the branching decision, we can see that we want to know where the following registers are assigned:

esi

ebx

edi

They don’t put up much of a fight, and the first basic block has our answers:

containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_1020C50 proc near

var_4= dword ptr -4

arg_0= dword ptr 8

arg_4= dword ptr 0Ch

mov edi, edi

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

push ecx

push ebx

mov ebx, [ebp+arg_0] ; ebx assigned

push esi

mov esi, ecx ; esi assigned

mov eax, [esi+40h]

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

mov eax, [eax+ebx*4]

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

push edi

mov edi, [ebp+arg_4] ; edi assigned

So esi is *this. We’ll need to find out what was placed in ecx in the function that called this function, as well as what the two arguments were.

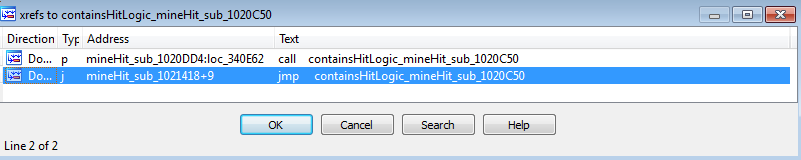

Looking at the xrefs for this function (x), we see that it could have been reached from two locations:

Following the code on our way out of this function, we can see that var_4 (rename to mineTriggerFlag) will be assigned the zero that ecx still contains, or whatever eax is when it comes out of containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_1020A42. This mineTriggerFlag value is returned in eax. When we come out of this function, we see that the return value can lead us to another block that is only hit in the triggered mine case. This would have been the next breakpoint we hit.

Something seems a little weird though. We just came out of containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_1020C50 (rename to mineFlagSetter), yet we returned to just after mineHit_sub_1021418.

Taking a look inside this function, we get some answers:

mineHit_sub_1021418 proc near

mov edi, edi

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

mov ecx, [ecx+10h]

pop ebp

jmp mineFlagSetter

mineHit_sub_1021418 endp

So that’s a bit sneaky, but we learn something important about the ecx value and the two arguments we are looking for. We can find them back in the function we were just examining containsHitLogic_mineHit_sub_1026FB7 (rename to callsMineFlagSetter), but we make note of the [ecx+10h] dereference and rename this function to sneakyCallAdjustsECX.

Back in callsMineFlagSetter, we examine these arguments:

mov esi, [ebp+arg_0]

push edi

mov byte ptr [eax+0C5h], 1

push dword ptr [esi+1Ch]

mov edi, ecx

push dword ptr [esi+18h]

mov ecx, dword_3A68B4

xor bl, bl

call sneakyCallAdjustsECX

test eax, eax

…we have a global variable, dword_3A68B4 (rename gameGlobal), and the two arguments which are offsets for esi. If we recall tileCases and the format string that used offsets 0x1C and 0x18 to read the coordinates of the game board tile that we clicked, we can form a good hypothesis here. If we examine the values at [esi+0x1c], and [esi+0x18], it does correspond to the tile we clicked. This makes sense. Our new hypothesis is that ecx holds the game board state, and the two arguments are the coordinates of the tile. The mineFlagSetter function is examining some member of the game board state at the given tile coordinates and determining if we stepped on a mine or not.

Let’s examine this member of the game board state, gameGlobal+0x10:

.data:003A68B4 gameGlobal dd 1BE2588h

0x1BE2588+0x10--> debug060:01BE2598 dd offset unk_1C21548

This is the object that was referenced at various offsets when the result of our tile reveal was being determined in the mineFlagSetter basic block that let to mineTriggerFlag Let’s examine it:

debug113:01C21548 unk_1C21548 db 0BCh ; + ; DATA XREF: debug060:01BE2598o

debug113:01C21549 db 19h

debug113:01C2154A db 32h ; 2

debug113:01C2154B db 0

debug113:01C2154C db 0Ah

debug113:01C2154D db 0

debug113:01C2154E db 0

debug113:01C2154F db 0

debug113:01C21550 db 9

debug113:01C21551 db 0

debug113:01C21552 db 0

debug113:01C21553 db 0

debug113:01C21554 db 0Ah

debug113:01C21555 db 0

debug113:01C21556 db 0

debug113:01C21557 db 0

debug113:01C21558 db 0

It looks like it contains information about the game board…pointer to a constructor, row count, column count, total mines?

The first dword 0x3219BC points to sub_34030E, and it looks pretty damn good:

sub_34030E proc near

var_14= dword ptr -14h

arg_0= dword ptr 8

mov edi, edi

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

push ebx

push esi

push edi

mov edi, [ebp+arg_0]

push 1

mov esi, ecx

mov ebx, offset aBoard ; "Board"

push ebx

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025584

push offset aSaveversion_0 ; "SaveVersion"

push 3 ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aMines ; "Mines"

push dword ptr [esi+4] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aHeight ; "Height"

push dword ptr [esi+8] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aWidth ; "Width"

push dword ptr [esi+0Ch] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aDifficulty ; "Difficulty"

push dword ptr [esi+20h] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

fld dword ptr [esi+1Ch]

push offset aTimeelapsed ; "TimeElapsed"

push ecx

mov ecx, edi

fstp [esp+14h+var_14] ; float

call sub_345606

push offset aFlagsplaced ; "FlagsPlaced"

push dword ptr [esi+10h] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aRevealedsquare ; "RevealedSquares"

push dword ptr [esi+14h] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aRevealsattempt ; "RevealsAttempted"

push dword ptr [esi+18h] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aFirstxclickpos ; "FirstXClickPos"

push dword ptr [esi+24h] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aFirstyclickpos ; "FirstYClickPos"

push dword ptr [esi+28h] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aRandseed ; "RandSeed"

push dword ptr [esi+2Ch] ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_1025647

push offset aBoardtiles ; "BoardTiles"

push dword ptr [esi+40h] ; int

mov ecx, edi

call sub_3458C4

push offset aBoardmines ; "BoardMines"

push dword ptr [esi+44h]

mov ecx, edi

call sub_345997

push 1 ; char

push ebx ; ArgList

mov ecx, edi

call mineHit_sub_10255CD

pop edi

pop esi

pop ebx

pop ebp

retn 4

sub_34030E endp

It would have been worth our while to rename some strings xrefs earlier.

In any case, we have just obtained an answer key of sorts for this object. The most interesting member is the [esi+44h] “BoardMines” member which started off our series of reads that determined whether or not we triggered a mine, recall:

mov eax, [esi+44h]

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

mov eax, [eax+ebx*4]

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

cmp [edi+eax], cl

jz short loc_340CD0

Knowing that arg0 (ebx) holds the column index, and arg4 (edi) holds the row index, we can walk through this series of reads and see how the mine locations are stored.

Firstly, BoardMines is deferenced.

mov eax, [esi+44h]

Then a column is dereferenced using offset 0xc as the base, the column as the index, and a scale of 4 (columns stored as ints):

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

mov eax, [eax+ebx*4]

Now that we have some pointer to a column object, we deference offset 0xc in it:

mov eax, [eax+0Ch]

Finally, we advance into this address by the row index and if we have a zero there, we did not trigger the mine:

cmp [edi+eax], cl

jz short loc_340CD0

So each column object stores information about all the mines in rows.

In the case of row 0, column 3:

01BED4B8 01 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

…we have triggered a mine. We can also do a little sanity check on this column. Does it make sense for our game board’s column at index 3 to have a mine at rows 0, and 4 only?

It does.

We now have all the information we need to generate an answer key. But can we get a few more chances at clearing the board if we ignore the return value from mineFlagSetter and force the branch?

We can set a breakpoint at the end of our basic block, force the branch to loc_346FF1, and see if anything breaks:

.text:00346FDE call sneakyCallAdjustsECX

.text:00346FE3 test eax, eax

.text:00346FE5 jg short loc_346FF1

so, the tile with the triggered mine is now disabled, and concealed but the game continues!

We just need to figure out one more thing. How can we cause a mine sprite to render on a tile? We’d like to render a mine on all tiles that we trigger, even if we had lives remaining.

Recall that we strongly suspected tileCases of handling the rendering of the sprites for our tiles. Let’s re-enable that breakpoint, continue execution, then click on a tile with a mine. When we break on tileCases, we can examine the arguments.

tileCases arguments

We hit tileCases before mineFlagSetter:

ecx - tileObject (0x1CD7E48, inspecting offset 0x18 and 0x1C confirms the column at index 7 and row at index 3)

arg0 - 0x9

arg4 - 0x1

arg8 - 0x0

argC - 0x1

arg0 will take us to case 8 in the switch, which has the accompanying accessibility text:

|55018|ACC|Row %1!d!, Column %2!d! Tile (Concealed)

…not exactly what we’re looking for, so we let execution continue. The code now breaks on our mineTriggerFlag block. This time, we’ll let the game ending branch execute so that a mine will be rendered. We hit tileCases again, but ecx is not the tileObject we’re expecting. This is where it helps to have played the game a little before reversing.

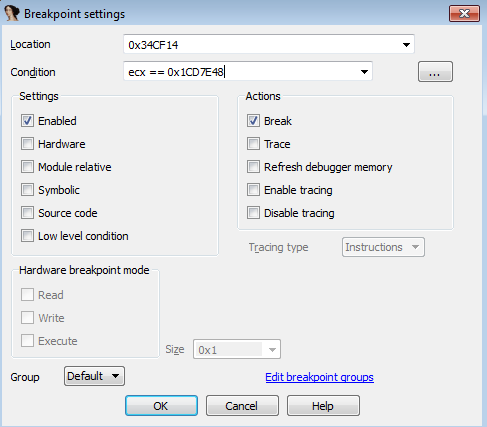

Recall that when the game ends on a triggered mine, many tile sprites are updated, not just the one we clicked on. So we’ll expect to hit tileCases several times. We can make this breakpoint conditional on ecx == 0x1CD7E48 to speed things up:

When we break on tileCases again, the arguments are:

ecx - tileObject (0x1CD7E48)

arg0 - 0x9

arg4 - 0x1

arg8 - 0x1

argC - 0x1

It seems possible that arg8 determines whether a mine sprite is rendered on a tile or not. Let’s test this by restarting the game, flagging a tile, and when we hit tileCases (unconditional breakpoint), settings the args (9, 1, 1, 1).

![]()

Excellent!

So now that we know how to render mines, read their locations in memory, and bypass game-ending logic without breaking (totally?) the game, we are ready to write our game hack.

Get your dev environments ready for Part 2 where we’ll be writing the code that makes use of this reversing effort.